46 all out: An autopsy

Great catches, ideal bowlers, a wacky pitch—everything came together to kill off this Indian innings. Consider this the autopsy.

Picture Credits - bcci.tv

How does a very good team get bowled out for 46 at home?

Turns out, easily. But we wanted to dissect what happened because this is not normal. I don’t see these many ducks when I head to the local park.

India have been on the verge of getting rolled out cheaply at home for a while, but today they fully embraced that low total. Great catches, ideal bowlers, a wacky pitch—everything came together to kill off this Indian innings. Consider this the autopsy.

SEAM: Rohit Sharma decided a while ago that tricky pitches should be treated with disdain. So he wanted to show everyone that he was still boss. We saw him try to play an on the up drive to a ball that jagged back in. It might have even beaten a normal defensive shot, but we will never know because all we have is this loose drive and broken stumps.

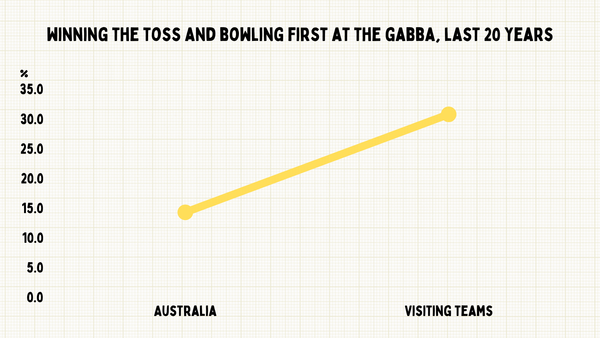

This was the moment he also probably thought he should have bowled first. But the truth is that even if you thought the ball would move around a little, no one expected this. There are tough for the first hour wickets, which is what he assumed this would be, and there are 46 all out wickets, which no one thought was possible.

Captain Hindsight never makes a mistake. But India got this wrong at the toss and in their team selection, and the wrong never stopped. Because it was not just seam, it was bounce.

BOUNCE: Virat Kohli got a ball that not only bounced enough to hit his glove but also seamed back into it. It was the best wicket ball of the day. And then you have to add in some luck, because the ball went straight at the leg side catcher. If he had been at leg slip, leg gully, or even a step back, Kohli survives. But like Goldilocks, New Zealand got it just right.

CATCH: Sarfaraz Khan forgot to use his feet. A lot of us are fascinated to see how he handles the ball zipping around from the seamers. But I’m not sure we learned much, because it felt like he accidentally walked out to the middle at the wrong time. However, it did take a pretty special Devon Conway catch to finish him off—the first of many.

LUCK: Yashasvi Jaiswal got a wide, short ball and tried to hit it to the rope, which is what you’re supposed to do. But he found Ajaz Patel, and that was it. On wickets like that, there's a theoretical discussion about whether it’s better to go out to a great ball or trying to hit a poor one. It’s the "if a tree falls in a forest" of cricket. But really, it sucks to get out to a bad ball on a bad wicket. That ball didn’t have his name on it—if there was writing on it, it was “hit me.”

On days like this, though, there’s always a lucky wicket.

Movement: The ball to get KL Rahul looks like luck, and it is. But it also came from the fact that the ball kept seaming until the 28th over. When does that happen anywhere without a Dukes ball?

If this ball went straight, KL would have gotten enough bat on it to pick up runs. But the seam movement caused the edge behind.

Fluke: This was the second wicket in a row from a ball down the leg side. You don’t expect to see a team bowled out for 46 with two dismissals down leg.

But it was also caught on the off side. Weird, right? That comes from the seam movement, of course, but still—if you're turning a poor ball down leg for one, you don’t expect to be caught in the ring on the off side. There’s a fluke element there.

But there’s also something else at play. New Zealand bowled brilliantly, swinging and seaming the ball. O’Rourke and Henry got nice bounce, aided by cooler conditions, and the stop-start nature of play helped. The last three wickets, though, came from three bad balls. Of the 191 deliveries bowled, these were definitely in the bottom five percent.

When Jadeja was out at 34/6, half the wickets had fallen to poor deliveries—after New Zealand dropped their easiest catch of the day. The smallest of comebacks was thwarted by a long hop and two balls down leg.

SAVIOURS: But it’s okay, because the lower order will save them. The lower order always saves them. We’ve even made a video on how the lower order saves them. This time, though, the lower order did not save them.

Ashwin got a ball that bounced first up—you can see how low his hands are and how high the ball was. Usually, by the time he comes in, the ball is softening. He does some clever batting with Jadeja, and they get things going. This time, the first ball broke the corner of his bat.

Resistance was futile.

END: Rishabh Pant was so confused by this pitch that at one point he tried a reverse pull shot off his thumb. That he managed 20 runs and was the last batter tells you how quickly it all happened. And for him, this wasn’t even the worst part of his day.

It was just the tail left to handle conditions that were clearly getting easier even as they batted. India could have fought back if New Zealand had not gotten one of their lucky wickets or taken one of their many great catches. Maybe we are only talking a score of 80, or 120, or even 160 at most. But having the best batting conditions of the day when you are eight wickets down is not ideal. Instead, Kuldeep Yadav was confused about whether he should let Mohammed Siraj face a ball.

It’s worth talking about New Zealand’s quicks. They had a swing bowler, a bounce bowler, and a seam bowler. On a day when the ball swung early under clouds, bounced higher than normal, and seamed longer than you almost ever see on Indian pitches, they had a weapon for everything. It was essentially a game under New Zealand clouds, with English seam movement and random freak Australian bounce. No wonder India kept hitting the ball in the air.

And those catches. New Zealand took two one-handed hangers out in the field. Matt Henry ran a mile to take one off a short ball. Twice, Indians were caught out by balls that could have easily fallen short. New Zealand had one of those days where all the half-chances stuck.

Like when Stuart Broad destroyed Australia at Trent Bridge or when the pink ball tormented India in Adelaide—sometimes all the play-and-misses and slashes through gaps turn into edges and catches. And once the collapse starts, those change rooms turn into ovens, and the frogs don’t even know they are being boiled.

That’s the part no one ever talks about in low scores—there’s usually a freak storm involved. To get India out for 46, it had to rain for over a day, the toss had to go horribly wrong, there had to be movement in the air and off the pitch, the ball had to bounce randomly, and all the half-chances had to go against them. Oh, and the opposition needed some luck for the fourth, fifth, and sixth wickets with bad balls.

Today, the right combination of toss, pitch, clouds, and catches meant 46 all-out happened. This is the coroner’s verdict.