Did the Evan Gulbis effect choke India?

Did this little-known quirk of limited overs cricket bring down perhaps the biggest juggernaut we’d seen in ODI cricket in 16 years?

Shout out to our new sponsor Nord VPN. Click on their link and get grab your EXCLUSIVE Deal. Get a Huge Discount off your NordVPN Plan + 4 additional months for free! If you don’t like it, cancel it within 30 days.

At the start of the World Cup, Australia had the fielders in quite defensive positions. It was clear that compared to other teams they were not putting pressure on. They were playing a slightly old-fashioned version of ODI cricket. Allowing for agreed-upon singles.

By the finals, the most notable was how far in their ring fielders were. They were diving and scrambling to stop even the simplest push. If you wanted a single, you had to really hit the ball hard. In other words, take a risk.

For Pat Cummins, there was something else because he was bowling offspin at 80MPH. He had tried that earlier in the tournament, and also before when coming to India. But it needs the right wicket, and he got that for the final. If the idea was to help India, weirdly what they did was help Cummins find form.

Cummins had struggled with taking wickets with the newish ball, he hadn’t got batters in trouble with the short one enough and wasn’t impactful at the death. His slower ball was the key. But what he did with it was really interesting. He set up a five-person legside field and bowled at leg-stump.

So when you see this wicket of Virat, it might look a bit weird. But what Virat was trying to do was guide to the offside, because the legside was blocked. This is no different than someone trying to cut an offspinner. And that is why the ball came back onto the stumps.

There is no way Virat Kohli thought he would be facing a field, or style of bowling, like this.

A lot of things happened in this game that India were not prepared for. They had been carried through the tournament like a prince in a Disney movie by their own form, and the fact they were just better than everyone else.

So how did India lose the World Cup final? The most obvious answer is that they are chokers. But a bit like how I fought back against using the term for South Africans - it’s reductive and doesn’t get us far.

They did lose the game, and you can’t throw this away because India may very much be the greatest ODI team of all time to lose a World Cup. This probably depends on how you feel about the South African ‘99 team or the West Indies of ‘83. But at worst, they are probably the third-best loser in a World Cup.

If we remove the choking narrative, the most logical reason for them losing is the Evan Gulbis effect. So the question is, did this little-known quirk of limited overs cricket bring down perhaps the biggest juggernaut we’d seen in ODI cricket in 16 years?

Gulbis was a bits and pieces allrounder from Victoria who over an eight-year career played 100 pro matches, mostly in T20. He was not a star, he was a fringe role player, who had three decent skills. He could hold a bat, good enough for batting at number seven at a pinch, but better at eight. He could bowl fairly fast for what was really more of a fifth, or even sixth bowler. And he was a good outfielder. The Melbourne Stars one described him to me as a three-tool player. But all of his skills were too blunt to make a big impact.

In his last game, Evan Gulbis did not bat or bowl. Melbourne Stars used their allrounders of Marcus Stoinis and Glenn Maxwell as their combined fifth bowler, and so the Stars used six bowlers in total, and still no Gulbis. They chased down the total easily enough with four wickets down, he was listed at eight and did not bat. This game was a semi-final, meaning next they would play a final, and Gulbis would not be picked.

In the final, the Stars wanted to use Jackson Bird as a bowler, and so Gulbis was dropped. Bird took two wickets. They went further ahead when their openers, Marcus Stoinis and Ben Dunk put on a big partnership.

Win predictors thought they were all but home. But they were batting very slow. You don’t really expect Dunk or Stoinis to have strike rates like this when they are making runs. And when they did lose wickets, a collapse happened as the new batters couldn’t score quick enough. In the end, the Stars would end up 13 runs short, despite the fact that Zampa made 15 runs from ten balls batting where Gulbis likely would have come in. So that means the bowler who replaced him, took wickets and the guy with the bat was handy. So why am I going on about Evan Gulbis?

Well for certain players - especially in must-win matches - the actual problem is looking at the batting list and seeing someone who can’t bat at eight. Or even seven in some teams. It means some batters - consciously or not - slow down. Earlier in that season the Stars had a batter, Nick Larkin at eight, such was their all-round depth. And they also had Liam Plunkett and his three first-class hundreds at eight. But Zampa and even Bird had been there as well.

Maxwell later admitted they should have gone harder. But Stoinis and Dunk had an ageing Bravo at seven, and Zampa at eight. With Maxwell, Handscomb and Bravo behind them, they thought they could also catch up when they got behind. But they never did.

Shardul Thakur started this World Cup in the Gulbis role. Hardik Pandya’s injury meant they pivoted to five frontline bowlers, and because four of their specialists can’t bat, a near vacant number eight spot.

Oh, and this is Kohli in the World Cup when Shardul played and when he didn’t. Is this conclusive? Not at all. But it is fun.

And this is India with and without Shardul this World Cup. They averaged more when he was there, and so maybe that makes up some of the story of why they batted slower without him. But I would suggest it was also because they just knew they had to be more careful.

My theory has always been that India hasn’t choked in major tournaments, but that they become defensive in knockout games with bat and ball, and I was not the only one to note this. England used it to beat India in the last T20 World Cup, essentially admitting they allowed India to go at their own pace.

Part of Australia’s plan, according to Bharat Sundarasen, was to get KL Rahul and Virat Kohli in together. Why those two? Well, we can guess. Rohit was going crazy this tournament, Shubman Gill scores at more than run a ball naturally, and Iyer doesn’t let spinners get comfortable.

But also, earlier in the tournament, Virat had gone slow against South Africa. He said at the change of innings that it was because of the shallow batting lineup. He said the Gulbis out loud. And you can see how much he slowed down in the middle of that knock. Only getting going at the end of the knock, and even then slowing down for his hundred.

Against Australia in the final this is even more stark - do not pardon the pun. He hits three gours on the trot early on, and then really sinks into the innings and on a slow surface against good bowling is happy with singles.

And I do mean that, this is every non-wide Virat faced, you can see there are only a couple of twos after his last four. But let me show you where Rohit gets out, and then Iyer. So you can see that until this point, outside of a good over, he had been scoring fine. From here he is all about singles.

And ofcourse if you look at just strike rates, Kohli’s still looks fine compared with KL’s. But that doesn’t account for the massive slowdown that happens at the end of the powerplay, and partly inspired by those two wickets.

If you just look at the middle overs, Kohli is still ten points higher, but his rate is now just above 70. And in truth, you can’t have two batters scoring this slow for 20 overs without the chance for issues later.

But we do need to talk about KL, because this was slow. Now clearly him and Virat decided this, because they both went at similar speeds after that third wicket. But we also know that no one needs to tell KL to slow down. In the IPL, he has defended many of his innings by saying he can catch up. And he has also admitted to batting long and slow because he doesn’t see depth in the order of his team.

He went very slow, from the start. Now part of that was them thinking they had to rebuild. No doubt this was on purpose, for a while. Then KL gets stuck from overs 18-23, when he was around long enough to be set. Yet he just stops.

Sometimes you get a couple of bowlers who pair up to freeze the game. But this was part of Australia’s plan. They knew not only would India slow down with this pair, but that they’d bat on autopilot. This was something Glenn Maxwell would do for the Stars. The idea is the batter is never that comfortable.

In this period from the 16th until the 25th, Australia used Zampa, Cummins, Maxwell, Hazelwood, Marsh, Hazlewood, Head, Starc, Marsh and Maxwell. Ten overs, seven bowlers. Not a single over at more than run a ball.

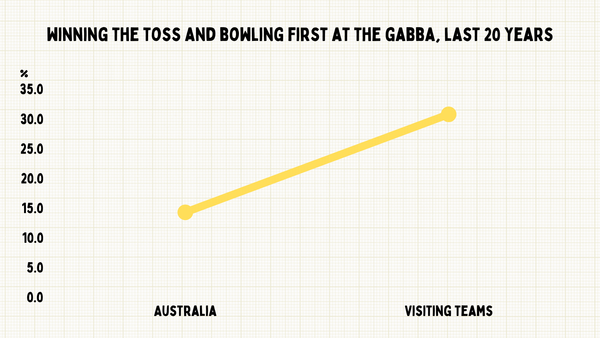

The pitch helped in all this, because it was not easy to bat on for that first innings. But remember that India was planning on batting first anyway. And most people assumed Australia would too. They flipped the script, and again showed great thinking.

But none of that means anything if KL and Virat go on to make hundreds. With how Australia had been bowling, Only Zampa and Maxwell had been above par for the tournament. Hazlewood had been fine, but nowhere near the force of other in-form bowlers. Cummins and Starc had been horrible. This was the first time all of Australia’s front liners, and also their three support acts, all bowled well. What a time to get it right.

It would be hard to say India didn’t play a part though. In the 37th over, KL Rahul faced five balls from Glenn Maxwell for one run.

He was well set, facing a fifth bowling option who usually needed backup, in the 37th over, with five wickets in hand, and he couldn’t get him away.

This shows how stuck he got. But all of his numbers are down, so clearly the pitch is playing a part here as well. But that doesn’t stop the fact that Kohli and KL did not put any pressure back on.

Clearly, these two players sometimes bat too slow. But they are also incredible run scorers - at least in part because of it. Put it this way, 245 players have 2000 runs in ODI cricket, ten have averages over 50, and two were set at the crease together. It is perfectly reasonable for India to believe that one of these guys would go on to make a big score because they always do. The fact that neither kicked on, and you could also throw Rohit in there. Having none of these players get close to a hundred is strange.

In the last four years, India played 74 ODIs, and on 73 occasions, one of their batters went beyond 75 runs. I know that was confusing because I said 73, 74 and 75. But basically, India averaged one batter scoring more than 75 per ODI over the last four years.

Now not all games India made enough runs for a player to make over 75. But the point is, they had the highest-scoring team ever when you look at averages, and in the one game, they needed one player to go big, not a single player passed 70.

Something else was weird in this game. For the first time this World Cup, India changed their batting order. Hardik and SKY had been their number six. But they didn’t back SKY to bat higher up when the pressure was on. Now if Hardik was fit, this would not have been an issue. But while I understand the idea of keeping Sky to come in later, I also think putting Jadeja up the order meant that they would continue to not put any pressure back on Australia. Put it this way, would Australia have sent out Maxwell or Inglis when this wicket fell?

Having a player like Jadeja is a wonderful thing, every team would ink him into their team near first choice every time for a World Cup inside India. But if you bat at seven - even as one of the best to ever do it - means you are flawed. Jadeja cannot score in the middle. So when he’s promoted, he will not change the scoring rate here.

Part of the reason is he struggles is he doesn’t like to attack spin much. So on a wicket where that was going to be tough anyway, he was likely to get stuck.

You can see a similar pattern in T20, where Chennai often hold him back as long as they can. So India sent out a defensive option, on a tough pitch, with fielders hunting him, and he struck at 40. India could have sent SKY in to put pressure back on Australia, hoped he lasted ten overs, and then sent Jadeja into bat where he likes to. And they would have had two aggressive options. Instead, they chose defensive and got stuck even more.

But there were other conservative issues as well. All tournament long, Siraj had been bowling with the new ball. But when India failed to set a decent total. They decided not to use Siraj up front. So Shami gets it, and he wasn’t quite as incredible as other games.

But what it really does is take away Siraj’s superpowers. India went from having five-strike bowlers to four. Again, it was another time when they chose the defensive option. And again, it did not work. Rohit never got defensive with the bat, but he did with the order and bowlers when it mattered.

Something else happened here that they might not have factored in, the Australians got reverse swing. That doesn’t happen as much for all teams now, and certainly less for Australia since they were caught with something you pick up at a hardware store. But KL and Jadeja were both dismissed by reverse.

Australia were also helped by the fact the pitch was hard to score on, and so the Indians really couldn’t knock the ball out of shape quickly.

In terms of the time of the match, SKY coming in for the 36th over is about where you want him to enter. So India got that part right, but, the issue was he couldn’t score. He was well low on his normal rate. This tells us that for all three of the other players who are getting blamed for scoring slow, that the pitch (plus bowling and fielding of Australia) played a huge part here.

SKY played seven attacking shots and scored a boundary. That seems very odd. So I wanted to know how often in T20 he scores a boundary when he attacks, 1.55 balls. Which is elite. But even though he hasn’t been as good at ODIs, he is still hitting a boundary 50% of the time he tries them. You don’t need to be good at maths to work out that one in seven is a long way from 50%.

This is the best example we have of the wicket being the main culprit. This means Australia winning the toss and bowling was even better than anyone thought.

But we also knew that Australia’s conditions would be different. They would be better and worse. The better was clear, look at all the games before the final, wickets were going at twice the rate in the second compared to the first innings. Only England lost when batting second.

But this game was different, not only because India were bowling with the statistically greatest striking bowling lineup ever, but because the ball did hop around a little bit in the dark. And this was India’s only chance. All they needed was one ball to get through Head, and who knows what would happen.

So in some ways, this match was like the inverse of the first time these two teams played, where Australia was defending a low total on a tricky day pitch, but that time Marsh dropped Virat, and this time, India just couldn’t dismiss Head. Now maybe you can look at the fact that Head put the pressure back on India.

Yet weirdly, when you look at the combined strike rate of Head and Marnus compared to the Kohli/KL scores, the strike rates aren’t that much different. The difference really is the length.

KL and Virat just didn’t make enough runs. The speed of the partnership is what we are focusing on, but in truth, the failure to kick on probably was what did it. Now, maybe they batted for longer, and still didn’t score enough. But the bigger failure is the amount of wickets, not the speed. Because what happened was Australia got to the number eight spot that Virat and KL were trying to hide. So India didn’t just fail to bat quick enough, they also failed to hide their flaw. It was that double failure that really led to Australia’s win.

The Evan Gulbis effect didn’t beat India. Well, not on it’s own. India came in with two weaknesses, that long tail, and a lack of a sixth bowling option. But what really beat them is a combination of Australia winning the toss, getting the call right, the pitch, Cummins and Starc coming good, Virat and KL not kicking on, India actually using their number eight, reverse swing, a pitch that even SKY couldn’t hit on, and Travis Head hitting the ball everywhere.

Think about all that, what are the chances of all those things happening in one game? 65% of the way through this match, India were still in front, two hours later Australia was holding the World Cup.