How great is Stuart Broad?

604 wickets in 33,000 odd attempts. Where does he end up?

How good was Stuart Broad? I mean that is the question right, because his place in the pantheon is not as straightforward as it should be. Stuart Broad is an incredible bowler, you cannot take as many Test wickets and not be one. But he was not the greatest bowler of his era, and he was not even the greatest bowler of his team. His average is very good, but it’s not good enough to make the case certainly.

Stuart Broad has a complicated legacy.

I think it has been popular to dunk on England players, and I get it, they get more attention than other players, and the whole colonisation thing. Broad could grate on opposition fans as well, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t incredible.

The question has to be just how good was he.

And for this, I will not be going into the incredible Stuart Broad theatre in his position as the grand wizard of cricket memes. Obviously, I am obsessed with all that sort of stuff with Broad, but I did a three-part documentary on that entire topic.

But for this, I just wanted to look at one thing, where does Stuart Broad fit in with the greatest bowlers of all time?

He has three obvious parts of his game that suggest greatness. Longevity, counting stats and sprees. Stuart Broad takes wickets in violent game - and series-altering rampages. His best days are an orgy of wickets.

This is the one that starts the legend for Broad. England batted him at number seven in this series, they were still thinking about him as an allrounder. He was the third change in this match as an afterthought because Australia’s openers were batting well. He came on at 73/0, and his spell finished at with Australia 133/8, him taking 5/37. He destroyed them. This spell proved that he was a top bowler, there was pace, movement and accuracy.

India were coasting with Rahul Dravid at Trent Bridge in 2011, Broad took five for five. It didn’t just end that match, but basically the series. Around this period these spells started to feel inevitable when they started.

New Zealand were chasing 239 at Lord’s in 2014, they made 68. Broad took 7-44 bowling unchanged.

Australia were halfway to chasing 299 in 2015 with only a couple of wickets down. Broad didn’t make the initial breakthrough, but he did completely mop up the middle and tail to ensure they never even got close and ended with 6/50.

That same series England went in without Anderson at Trent Bridge and bowled first, the Test was over before lunch as Broad took 8/15 and gave the world new memes.

And there was the 6/17 against South Africa in what was shaping up as a close game until again Broad just massacred them. His big spells don’t turn games, they end them.

What I think makes this all the more amazing is how often Broad has managed this in five-man attacks where there is plenty of quality bowling around. Like Curtly Ambrose took wickets like this, but often it was only him and Walsh. The same with bowlers like Fazal Mahmood, Richard Hadlee and Murali. But Broad did these despite the other bowlers sharing the load. That shows that this was his main thing.

The reason was probably because he was such a great combination. He is very tall, and he routinely has some of the highest release points in the game. He can use that to get a ball to jump up from a length, but also for short balls.

For his height, he can get more swing than bowlers. The ball is still sometimes a little floaty, but this gives him another option. And at his pace and height, swing is a huge combination.

Ofcourse like most taller bowlers he can actually just hit the pitch. He’s probably not a natural back of a length bowler like McGrath or Ambrose, but again it’s something he can use on the right day. He also wasn’t quite as accurate as them, he can struggle with line and length at times, nothing massive, and he’s still an above average placer of the ball, but he isn’t elite.

He can also move the ball in both directions. That is always a huge advantage. Unless you have a Richard Hadlee outswinger or a Courtney Walsh off-cutter, you need the ability to go both ways.

And he was fast. Never quite express, but certainly over 90MPH when he got it all working. This is a pretty incredible combination and when he got it right he was basically unplayable.

But he couldn’t do that all the time. There are probably three major reasons for this. One is he wasn’t born a bowler. He was a batter until late teens when a trip to Australia turned him from a friendly medium pacer into a quick bowler. So unlike many of the best wicket takers of all time, he was probably not as grooved in his bowling action at a young age.

Someone sent me an article recently where I described Stuart Broad as the Nic Cage of bowling. Cage will take risks, perform erratically, pick terrible films, choose the wrong way to perform a role, overact and then occasionally perform so brilliantly that he makes an entire film. While doing all this he also divides opinion.

Broad is like that with the ball. He was always tweaking, fiddling and looking for ways to change things. Whereas a grizzled bowler with his natural skills might just hit the pitch on a length a bunch of times.

But ultimately I think it is about coordination. When people talk about Broad with his knees up, they are saying he is trying harder. I think it’s because he has trouble finding that rhythm. And his natural skills are still good enough that he is a threat when he isn’t clicking. But when he gets everything right, pace, bounce, accuracy, height, and movement, in one package is nuclear.

How great a bowler can you be if you regularly get dropped? This is the question I have about Broad always rattling around my brain. But focusing on drops is tricky. Especially as England are pretty full on with resting and rotating.

Also, what is regular? Many players are dropped as youngsters or even might miss the odd match as they get older. But what we’re really looking for is players dropped regularly from ages 26-34.

Ofcourse no one keeps stats on that. But there are a few times when Broad certainly missed out on form. He complained of illness on an India Test, but then bowling coach David Saker made it clear they thought his form was an issue.

There he was dropped for Steve Finn, who was obviously a tall fast bowler. He was not as skilful as Broad, but a little quicker.

In 2018 in Sri Lanka, he missed out again. And there are a couple of problems that Broad runs into on these Asian surfaces which is where he was dropped a lot. Anderson exists, and he is clearly going to get the first spot. Then England have all-rounders that can bowl seam. In Galle for 2018, Broad was dropped because England had Sam Curran and Ben Stokes as their second and third seamer.

I think these are less of an issue.

The bigger issues are the three against the West Indies. The first at Bridgetown was a big deal. And Broad was straight back in after that.

A year later England selector Ed Smith was at it again, dropping Broad this time at home against the West Indies. Broad really didn’t handle that well.

And then he and Anderson were dropped together for the West Indies tour last year. That was not Ed Smith, so at least that had changed. But it was the West Indies again.

He actually has a fairly ordinary record in the West Indies, though he played in the shit ball flat pitch era when taking a wicket was like catching a fly in your teeth. But he wasn’t dropped because of this, England just wanted to move on.

So there is no doubt that Broad was dropped multiple times throughout his career. Of the bowlers with 400 wickets, there are actually quite a few that have been dropped, but all of those are spinners from Asia when they travel.

Great seamers don’t usually miss out on a spot. You look at all the guys over 400 wickets, they are first choice no matter the conditions. But the guys underneath that you start to see that they do get dropped a bit. Guys like Southee, the Mitchells, Starc and Johnson, are just more likely to go through periods where the team is not feeling them. All-time greats don’t usually get dropped this much, though they also don’t take 600 wickets and live through 24-hour news cycles.

His argument for the greatest has to come via his longevity. After Anderson, he has the most Tests of a seamer. There are two ways to think about this. One is to say that England play an extraordinary amount of Tests in this period, and so ofcourse these two are there. But the other is that while that is 100% right, they still had to bowl all those overs and recover from more back-to-back Tests than anyone in history has. Bowlers like Walsh, Hadlee, and Bedser would probably have handled this workload, but most bowlers wouldn’t.

That said, inside the game, Broad had a pretty decent run of it. He’s a long way down the list of balls per Test list. England haven’t overworked him that much. They milked the most out of him, even by resting him - despite him hating it.

Let me just highlight some players here. Broad bowled six overs a match less than Glenn McGrath, his idol. That was another era, what about someone who has played at the same time as him, Tim Southee, five overs a match less than him? And also a couple less than Anderson, who at least is closer to him on the list. So Broad doesn’t bowl a lot in a match.

However, if you look at by year, he still bowls a lot of overs. He’s only bowled the most once, but he has been top five every year of his career. It’s a lot of overs to bowl at the top level, no matter how you work it out.

Because players don’t all play the same amount of Tests you also have to look at span. I think this matters because if you have a player for 12 years, whether you play 60 or 110 Tests, that means that bowler doesn’t need to be replaced for that entire period. You never find that many great bowlers, let alone Test level ones, so the amount of years really matters.

Broad lasted 16 years. His mate Anderson makes that look silly. But there around Jimmy are two all-rounders. Because you can extend yourself a little bit with the bat at the end. In fact next to Broad is Kapil Dev. But you can see on span, Broad is certainly at the heavy end of this.

Seam bowlers simply don’t last 16 years. That he did means that England had their first two names pencilled in for nearly every match for a decade and a half.

There are things that started to help Broad with longevity. England started to use Stokes, Archer, Wood and even Woakes to bowl the dog overs in the 40-80 period. From 2014 onwards Broad bowls 15% less of these overs than before. That all matters. Because those are the gut-busters.

Soft balls, flat pitches and set batters. And having Stokes especially who a specialist for this allows for Broad to bowl more when the ball is doing more. And worry about bowling fast short bowling spells that kill seamers.

There are things in his career are not exceptional, and I think the most obvious is probably his wickets per innings. I would not expect him to be high on this list, but taking less than two wickets per innings is not that ideal. You see him down here on the list with the Asian seamers and all-rounders. He did have five bowling options in a lot of his Tests, but so did many of the bowlers higher than him.

His number here is not terrible, but it is also not great.

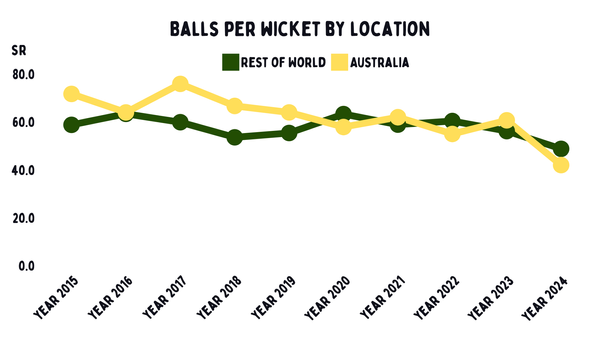

Also Broad took a long time to get his wickets. This is more remarkable because of the days he took them seemingly every ball. But he was very much a seamer who took a long time to break through when he wasn’t destroying entire innings in a spell.

Here is Broad versus the best batters in the world. He’s known as a top-order bowler, so I assumed he would do pretty well. There is clearly one massive elephant in this, Graeme Smith. A lot of this was early in Broad’s career. And he was completely unaware of how to bowl to left-handers then. That doesn’t mean Smith didn’t eat him alive, or that it doesn’t count. But let’s just remember Smith was over 200 against him and move to everyone else.

Let’s look at the others who average 50 against him, Smith, Labuschagne and Dravid are all top players, you can’t really worry too much about them. You also have Elgar, Vijay and Mitchell on here. Slightly more surprising to see Elgar, being a lefty.

While he doesn’t average 50, Kraigg Brathwaite averaging more against Broad than in the rest of cricket may explain why England keep dropping him for West Indies matches.

Let’s look at who he dominates, Warner is obvious, but he was better against Michael Clarke. Shane Watson and Ross Taylor are two he was on top of. There is also Chanderpaul, Younis, Misbah and Rahane who really struggled with him. Although AB de Villiers was perhaps the one you notice here the most. He dismissed him in 50% of their contests. That is an incredible record against someone that good. And I cut this all off at 300 balls, but across nine innings Sachin Tendulkar also averaged 13 against him.

Hard to look at this list and not think he’s an incredible bowler.

One reason I think he does so well against good batters, other than just his obvious new ball skills, is the fact he is a good learner. This is Broad versus left and right-handers in his career. This first mark is basically because of Graeme Smith, so for the second time I will have to take him out to show you this better.

You can see he works out the righties really quickly because that comes naturally to him. But left-handers took an age. He was actually assisted a little when he started to lose his wrist position it moved the ball away from them more. It was really coming around the wicket that changed everything. But the point really is that Broad has been a bowler who has got better throughout his career in almost every way. He was always thinking.

But that slow change to getting better separates him from all-time greats. It took him an age to get his average under 30. 73 Tests. That is the same number of matches that Mitchell Johnson played. Some of that time his batting helped, although that was slipping well before he was hit in the face.

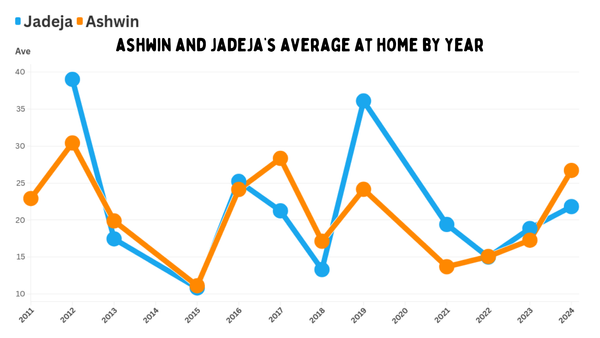

He actually gave England plenty of chases to move on around 2012. They didn’t, and they - and Broad benefit from this. This is Broad and Jimmy together. Notice anything? Around 2012 they are both averaging around 32, by 2014 they are both under 30.

Neither of them will ever average over 30 again.

So what happens here? I am going to guess it is three things. England step up their analysis, or at least, their bowlers and coaches fully buy in. They become the smartest team in the world with their plans, helping out a lot.

Also - thought a little later in 2015 - they don’t have to worry about white-ball cricket any more. They are red ball specialists.

But I think the most major part is that Anderson, and then Broad, perfects the Wobbleball. By 2014, Anderson knows it well enough to start teaching it to others inside English cricket.

In 2017 we see a global drop in averages starting, and by 2018, it’s off the charts. And it has stayed there for every year until this one. We know the reinforced seam of the Kookaburra ball plays a part as well. But essentially in this period, everyone gets better.

Broad’s average drops ahead of the curve, by the time the dip happens he’s a star. Although he has a year where he struggles during it. Unlike many modern bowlers, it isn’t the pace-playing pandemic that changes his numbers. But that is only because he was playing under those conditions beforehand.

Let’s add his mate Anderson here as well. He is very interesting, the first couple of years of bowling with Broad he’s marginally better than average. Then during England’s great years he dominates, before slipping back to average again. Then from you can see that after years of up and down 2014-2017, Anderson just drops. And Broad joins him for those years. From 2014-2016 this does read like two guys who know something no one else does.

Then as to how to bowl the wobbleball gets out, they’re still good, but so is everyone.

Just to go back to Broad, I have split this up. The first section is his playing as an all-rounder through until he is dropped versus India. At that point, with his batting dropping off even before Varun Aaron hit him in the face, England could have moved on from him. But then you can see that he starts to dominate in what was still a good batting period for the world. And then he continues to do that in the pace playing pandemic as the Wobbleball takes over.

So either Broad got good before the wobble ball, with a combination of Stokes doing the dirtier work, the analysts helping and just him understanding how to get the most out of himself. Or he was starting to use the wobbleball as well, and therefore from 2014 onwards, he was getting an advantage that the rest of the world wouldn’t see for a while.

But that is what teams do, South Africa won a Test series on the back of one player working out the wrong’un, and teaching his provincial teammates. Broad still had to be good enough to use it well, and he certainly did.

The last thing to talk about is the wickets. We can talk about the wobbleball, how he was dropped, Stokes helping his longevity, his wickets per innings and the best batters in the world. You could make an argument that is Courtney Walsh to Jimmy Anderson’s Curtly Ambrose. But let’s just look at the poles.

There are two things that matter, wickets, and how many runs they come at. 45 bowlers have between 200 and 300 wickets. Another 20 are between 300 to 400. 10 more from 400 to 500 victims. Only two have 500 to 600. Five players in the history of our sport have 600 plus, one of them has 700, and the other 800.

You can argue a lot of things about Broad’s place in history, but being one of five bowlers - and only the second seamer - with 600 wickets is something incredible. They don’t give many away. He had to stay fit, work out trends, bowl around the work, fight injuries, and keep running in. No matter what.

For most people what will matter on what they like more, bowlers with more wickets, or with lower averages? That is something you need to work on your own. But I have known enough seamers to understand that taking 600 wickets at any level is something incredible. To do it in Tests is mind-blowing.

Broad was a nepo baby with freakish physical gifts who dropped into the most professional culture in cricket. He had access to sports science that other bowlers never got. And he benefitted from having a bowling genius next to him. But none of that explains away running in 33698 times and taking 600 wickets.

But average does matter, at the end, how many wickets you got for how many runs is how we look at Test bowlers. And his record on that is not great. That’s not a slight, being Marshall, Hadlee, McGrath, Garner, Wasim or Ambrose is the god-tier. But he’s not there on average. He did bowl in a tough era at the start of his career, but certainly not at the end. And he also bowled a lot of matches at home, with a very nice ball.

In the end, Broad’s average is 27.68. That probably isn’t great enough for a seamer from England to be an all-time great. But because he played for 16 years, he certainly made his push.

If he wasn’t an all-time great, the many moments he left us were. He was never the best bowler of his era or even his team. But he was incredible theatre.

Right before his final wickets, he trolled Australia by taking the bails off, rehashing a meme he had done days before. Broad was at once the story, and conscious of it. The lead actor and director of his own narrative. Whether he was just an England great, or also an all-time great is subjective, but it would be hard to argue he was a great entertainment.