No run(s) for Marnus Labuschagne?

What brought about the decline in Marnus Labuschagne’s run-scoring?

Download Hitwicket Cricket Game 2024 - Be the Owner, Coach and Captain of your own Cricket Team | The Ultimate Strategic Cricket-Manager Experience | Not a fad. No ads.

Marnus Labuschagne is dropped by Virat Kohli in slips off only his second delivery. With 150 runs on the board, dropping the number three is massive. For the next hour, Kohli gets to think about it as Marnus bats on. Watching a batter you’ve missed make runs is a special kind of frustration.

That is not what happened to India, because Marnus’ innings goes nowhere. His misery—and that of the watcher—is ended when Mohammed Siraj pins him leg before wicket. He was seeing the ball so poorly that he also reviews, and has to watch it crash into leg stump. He saw off five teammates, but in all that time, he made only two runs. This drop didn’t matter.

But drops are part of the Marnus story. CricViz’s Ben Jones tweeted about the catch success percentage of Labuschagne versus pace compared to all batters. In recent times, there hasn’t been a huge difference. In fact, he has had relatively fewer dropped chances since the start of 2022. But in the time period before that, less than half of his chances against seamers were caught.

Aussies are asleep, keep it on the quiet pic.twitter.com/0QgAMlwPWu

— Ben Jones (@benjonescricket) November 27, 2024

Marnus Labuschagne averages only 27.41 in 13 Tests since the 2023 Ashes. So, is this just a reversion to the mean? Was his early career an outlier? What is the truth about this man and his divergent career? Why has Marnus Labuschagne started making no run(s)?

"Marnus is a young player with plenty of potential and a great work ethic. He has performed well in the Sheffield Shield, has shown he’s a good player of spin for Australia A in India, and is an elite fielder who offers added variety with the ball as a leg-spin option." This is what selector Trevor Hohns had to say on picking Marnus Labuschagne for the tour to the UAE back in 2018. Legspin, playing spin, fielding and work ethic were the reasons he was there.

At that stage, he hadn’t made too many runs. He never averaged over 40 in a Shield season till then, and this was well before the Kookaburra ball change in 2020/21.

Oddly, his breakthrough season in first-class cricket wasn’t for Queensland, but Glamorgan in the 2019 County Championship. He was the second-highest run-getter in Division Two, and also picked up 19 wickets at 38.1 runs apiece.

He somehow went from that to a mini-Steve Smith in the same summer. He was the poster boy for the concussion substitute, and was suddenly facing peak Jofra Archer—nothing like the Division Two bowling of before. He survived that, and made more runs in the 2019/20 home season.

His mannerisms and bromance with Steve Smith meant that Australia had two of these quirky run-getters at the same time.

Somehow, Marnus Labuschagne had gone from a struggling first-class player to one of the best batters in world cricket. His career average was 60 after 52 innings. That is some peak.

40 innings later, it’s less than 50. We looked at his 20 innings rolling averages. He has two careers, one with an average of 60, the other going at 30. He is half the Marnus we first saw in Test cricket.

What brought about the decline in Marnus Labuschagne’s run-scoring? The first thing I’ve noticed is that he’s being dismissed differently than before. He is getting bowled and LBW less often against pace now compared to the start of his career—about 21% now, compared to 35% back then.

That’s a—pardon the pun—big drop.

When I was working for ESPNcricinfo, there was a theory in the office that some of Bairstow’s early numbers might have been influenced by being dropped a lot. This started a huge discussion on drops in general. The players who were dropped the most were usually New Zealand top-order players. That was during the period when the Kiwis couldn’t find an opener. So, the players they had struggled and often nicked the ball. But something about the opposition catching was off. In fact, most of the list of the players with a high percentage of drops were top-order players. Slip catches are tough. Middle-order players were often caught at a higher ratio, because their chances are usually miscues inside the circle.

But Bairstow’s drop percentage was certainly higher than pretty much every other middle-order player. So, it was clearly an issue. In 2019, Bairstow averages less than 20, and his struggles continue when he’s back in the side in 2021. All his catches were taken in those two years. So when he was among the runs, he was being dropped a lot. When he wasn’t, every chance was taken. That seems simple.

But look at the amount of chances each year. From 2016 to 2018, he gave 37 chances, averaging 0.54 chances per innings. He played 36 innings in 2019 and 2021, but the number of chances was just 11. The chances per innings reduced to 0.31.

It wasn’t that he stopped making runs because fielders started catching him more often. They bowled differently as well. It was in this period that teams started attacking his stumps and pads, which meant that any off-side catching options were rare. It looks like the drop percentage means far more than it does. But you have to look at where teams bowled at him. Bairstow wants the ball outside his off stump, or short. The last place in the world he wants it is at his stumps.

The moral of the Bairstow story is confusing, but let me try to stick the landing here. When he made a lot of runs, teams bowled wider to him, and he loved that. He swung hard at the ball and was dropped as he made runs. Then the bowlers went after his stumps, he stopped producing as many catches. When he did, they were taken. But the line was what slowed him down far more.

Bairstow wasn’t making runs because of drops, but because of the line.

Marnus Labuschagne is not a typical Australian cricketer. He is a South African by birth, and one with a name that is not as common in Australia. To South Africans he is La-boo-skach-nee, and to the Aussies, Lab-u-shane. He doesn’t mind either, he just likes to be Marnus. But that does mean he stood out.

Marnus is a devout Christian. According to the 2021 Census, about 10 million Australians aren’t religious. Now, religion has played a part in Aussie cricket before, when the Protestants and Catholics didn’t get along. But it is barely mentioned most of the time.

Marnus is religious in a way that hasn’t been seen much in Australian cricket for generations, including placing an eagle sticker on his bat to represent a quote from the Bible. Aussie cricket is not an easy place to be an outsider, and Marnus’ name and beliefs do that.

Then there is his disposition. He’s more pixie sprite than hairy warrior. He’s like a small boy on stage for a show who has learnt the songs and accompanying moves with a passionate desperation to show everyone. But he’s performing his own separate show with nerdish enthusiasm and individual flair.

It was clear that the old guard didn‘t like him. Andrew Symonds and Shane Warne were caught making fun of his ADD (their uneducated medical diagnosis), and how, in the old days, Marnus would have been beaten into submission. There is feeling like an outsider, and there is hearing that on TV from two cricket heroes.

There just aren’t many Australian players like Marnus Labuschagne. Steve Smith is an outsider. But while these two might share an unbreakable hetero-life bond, Smith feels like he is inside the tent. Marnus is dancing to songs only he can hear from the outside.

When you look at the history of Marnus Labuschagne and dropped catches, it goes back to 2021. People were quick to notice the pattern.

Shiva Jayaraman's analysis for ESPNcricinfo was one of the best looks at drops and luck. At that stage, Marnus did have the most drops, so it made a really compelling case. But the piece went deeper and looked at percentages.

Shiva found a batter who was dropped more often than Marnus—Bangladesh’s Mushfiqur Rahim. Why didn’t we obsess over him? Is it because he didn’t start his career this way, or because he just didn't make as many runs? Perhaps being a veteran from a cricket nation outside the Big 3 meant that fewer people around the world noticed.

In fact, I don’t remember much about Abid Ali or R Ashwin being dropped a lot either. But the most interesting player here is Usman Khawaja, who not only got dropped a lot, but also went on to make plenty of runs himself, often with Marnus.

After Khawaja’s eight drops, he averaged 52.4. So, not only were his catches missed at significant rate, he went on to be great with the bat in those innings. Almost 50% of his runs came after drops. Khawaja had luck, but he still batted like a legend after being dropped.

Which brings us to Shiva’s last stat. According to this, if every first chance had been taken, Khawaja would have averaged 22.59, and Marnus 42.38. Everything still suggested that although Marnus had been lucky, he was batting really good to begin with. He added 567 runs after drops, but 1653 before them.

About a year later, the calls got louder as Marnus had an incredible innings where he had 29 edges and 16 play-and-misses up to 40 minutes before lunch on day four, according to Australian statistician Lawrie Colliver. He was also out off a no ball. In that match, he made a double century in the first innings, and added a hundred more in the second.

At that time, Colliver checked that if Marnus had been caught every time he gave his first chance, his average still would have been 44. That is still really good, especially for a new batter who did not have a great first-class record. This was at a time when many of the best players in the world were struggling.

Marnus was good before being dropped, and good after being dropped. The best way to understand this is he made a lot of runs, and got a lot of drops.

When the wobbleball takes over, we see players in the game who were doing great suddenly stop making runs. Virat Kohli and Steve Smith have never been the same again; others were just dropped. Greats, good players, and replacement level batters—all struggle. The same batters, fewer runs. Only five of the 17 batters average more.

This is why we refer to this era as the pace playing pandemic. It changed cricket entirely.

But there were anomalies. Babar Azam doesn’t make many runs before the pace playing pandemic. But when bowlers change their lines and lengths to fuller and straighter, he goes on a tear. Four players come into cricket in this period, and they all score plenty of runs. Three Kiwis—Tom Blundell, Daryl Mitchell and Devon Conway. The last of that group is Marnus.

All of their averages are incredibly high. At various times, they are among the best batters on the planet. Currently, they're all struggling. My theory—and we’re through the looking glass here, people—is that they all came in with techniques that were better for the full length aimed at the top off stump. But as teams saw that didn’t work, they came out with personalized plans, and that change caught them out. Figuratively, in some cases.

So, what’s different for Marnus? Before 2023, he was brilliant against balls that seamed a lot—averaging 45. However, since 2023 that’s dropped to 11.

Since losing his form, he’s tried to change his impact points to further down the wicket, like nearly the entirety of world cricket. Marnus also started to stand outside his crease to intercept this length, changing his overall position on the crease by about 25 centimetres. That is a noticeable difference.

He played 13.8 false shots before he was dismissed till 2022. Usually, it would be about 12 mistakes per wicket. But every player is different. Players with hard hands or who hit in the air a lot usually have less mistakes than those who play late and along the ground. After that period, it has been just below 11 mistakes per wicket. So it isn’t that he’s started going harder at the ball, which suggests a reversion in luck.

But when we look at his false shot percentage by 10-ball blocks, we notice that he has clearly been starting worse. If a batter is making mistakes more frequently early in their innings, their chances of getting out for a low score will increase. A mistake when set is different often does not lead to a wicket, because players are making smaller errors at that point. They are more in control. For example, even if it hits the inside part of the bat, it might not be a small inside edge back onto the stumps but a bigger one into the pads.

Maybe he is simply making more mistakes early, and they are far more glaring. Plus, he almost never looks set now, so there is an element of almost every error looking potentially fatal.

What about when he goes in to bat? Has that changed? The median entry points haven’t moved by a lot, but he’s still coming in earlier than he used to—6.5 overs now compared to 8.2 in the previous time period. I don’t think Australia’s recent issues with openers have caused a problem for him. Warner was struggling for a while when he was doing well.

But how much did that affect his returns during his best years? When he came to bat in the first 10 overs from 2018 to 2022, he would average above 65 in those innings. If anything, that dropped to under 50 when he came in after 20 overs. Since 2023, his returns have dropped the most when it comes to the first 10 overs, but he only averages in the mid-30s even after that. That is a concern, because this is not just a new ball issue.

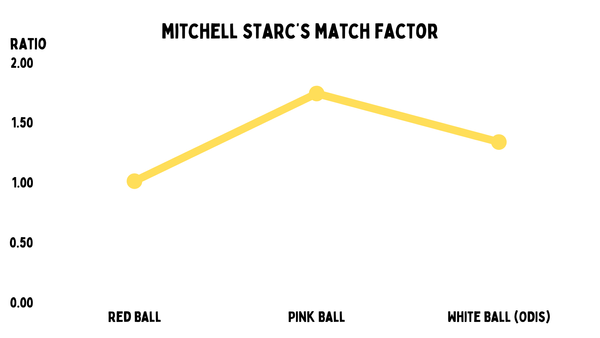

From his debut till the end of 2022, he had a match factor of 1.69. Look at the names around him on this graph. He was well and truly one of the finest Test match batters in the world.

But he is certainly a more dominant batter at home than away. He averaged more than twice the rest of the top six batters in Australia in that time period, while being a par batter on the road. But since 2023, his match factor has more than halved at home. It is less than one both home and away.

Only four batters with at least 750 runs have a lower overall mark than him since the start of last year.

Although his overall away average of 36 isn’t great, we have to take into account that he has played in some difficult conditions across the globe. The two countries away from home where he has batted the most are England and India, and his match factor is greater than one in both. It is also above one in Sri Lanka. He got a few starts in Pakistan but didn’t score big runs in what was a very high-scoring series. He also had only one noteworthy score in New Zealand. So his away record is probably better than his average, but he was clearly outstanding in Australia.

At home, the Kookaburra ball upgrade didn't really impact his numbers until recently. The only other season where he did not average above 50 was in 2021/22, which was when the Ashes were held. Those games were quite low-scoring in general. Labuschagne was still among the top run-getters of the series, only behind Travis Head.

This is a beehive of all of his dismissals versus pace. From 2018 to 2022, you can see that he‘s been out a bunch of times when his stumps were attacked. But if you check the points since the start of 2023, you’ll see a pattern just outside the off stump or in the channel.

Almost everything has dropped off from his peak, but you can see how much better he was against the balls in the channel—averaging 71. Now, that has gone down to just above 18. Those numbers have fallen off a cliff. When the ball is wider, his mark halved from 52 to 26. He went from almost never getting out to it to being dismissed very frequently.

His record against the full ball has been similar, but it has changed for every other length. The six to seven-metre good length had the biggest drop-off for Marnus, going from 52 to just 9. Again, just a shocking fall.

If we look at both line and length, we can see that the deliveries that land in the six to seven-metre length and are in the channel outside off have troubled him the most. He averages 1.5 versus these since 2023, compared to 28 from 2018-2022. An average of 28 is great, because the global average in that time period was 16.

So, Marnus has gone from being almost twice as good to basically having a negligible average against the exact same ball. Let’s say we do think the drops matter. There is just no way they can explain this drastic change—unless before he was being dropped every time, and now everything is being caught.

Earlier, teams were bowling straighter to him because that is where you bowled the wobbleball. But that clearly didn’t work with Marnus, so they have moved outside off. The fielders and batter were the same, but the line had changed.

Now the bowlers are seemingly playing for more caught behinds. And the key word there is caught.

The 'Lucky Marnus' tag has taken over now. But it is far more complicated than that. Neil Wagner rarely had catches dropped off his bowling. Do we infer from this that his teammates loved him so much that they never wanted to let him down? Or was it more likely that he didn’t bowl for slip catches, so a lot of the chances were easier?

Not all drops are the same. But one of those rare missed chances off Wagner was when Marnus was batting. We went through as many as drops as we could find on NV Play, Cricbuzz and ESPNcricinfo, and we still weren't sure if we found them all.

From what we noticed, it did seem like most were straightforward. But there were a few half-chances as well. It was also clear that he plays with soft hands, and a lot of his slips catches were low, which might add to why he is dropped as often.

There is also the undeniable fact that generally the players who get dropped a lot are out there batting more often. That is because they are in longer, and often their chances are from more full-blooded shots, rather than half pokes early in their innings. Not all catches are the same either. We simply don’t have the equipment in cricket yet to make the most educated call on whether Marnus made a lot of runs because he was dropped a lot.

Catching stats don’t even match across different databases. One person’s drop is another’s near miss. A tough chance for me might be simple in your eyes. And with cricket also being so secretive with its data, this all becomes a mess. So we don’t really have the technology which would involve spatial tracking data, and we’re also short of the basic information.

But let me put this out there. He was making plenty of runs before and after the drops in that earlier period. Now he isn't, regardless of whether he is dropped or not. It does suggest that he was simply batting better in that period than now.

Maybe it is as simple as the fact that he was someone who hadn't made too many runs in first-class cricket, came in with a technique that helped during peak wobbleball era, and now the bowlers have adjusted. Or maybe he’s just seeing the ball terribly right now and is low on confidence. He looks as likely to make runs as he is to colonise Mars and open a baklava shop there.

India could have dropped him several more times and he still wasn’t going to score runs. The question of the drops is kind of separate to what we are seeing now. Marnus used to make runs, whether he was dropped or not. Now, in his own words, there are no run(s).