Steve Smith: the all-time good of ODI cricket

He timed his retirement as well as his legside nudges - but where does Smudger stand in the ODI pantheon?

There is one question I get asked a lot, and I think it’s because it’s not discussed or really thought about: how good is Steve Smith as an ODI player. The T20 question with him has been answered long ago, his Test career was goated before Sandpaper or Jofra Archer’s bouncer. But as a 50-over dude, he stands somewhere in the middle.

Two World Cup medals should validate greatness more often than not. But in an era where white-ball cricket has evolved faster than a Pokemon on meth, an average of 43 makes things complicated. A strike rate of 87 isn’t groundbreaking either.

Steve Smith’s 50-over career in an Australian shirt amassed 170 games across 15 years, which tells you a lot about ODI cricket’s decreasing popularity. 5800 runs in 154 innings, with 12 tons and 35 fifties, is a significant tally, but the fact that Virat Kohli has scored more runs in singles alone makes it look puny.

For a man known for making runs, he just hasn’t made a lot in 50-over cricket. And yet, two World Cups, plenty of incredible innings, his legacy is still, at best, complicated. His retirement from the format didn’t end with an outpouring of emotion, even from the Smudgeheads out there who are obsessed with his every move. He was yawned into 50 overs pension.

But he did play it, and win a lot. So just how good was Smith in cricket’s middle child format?

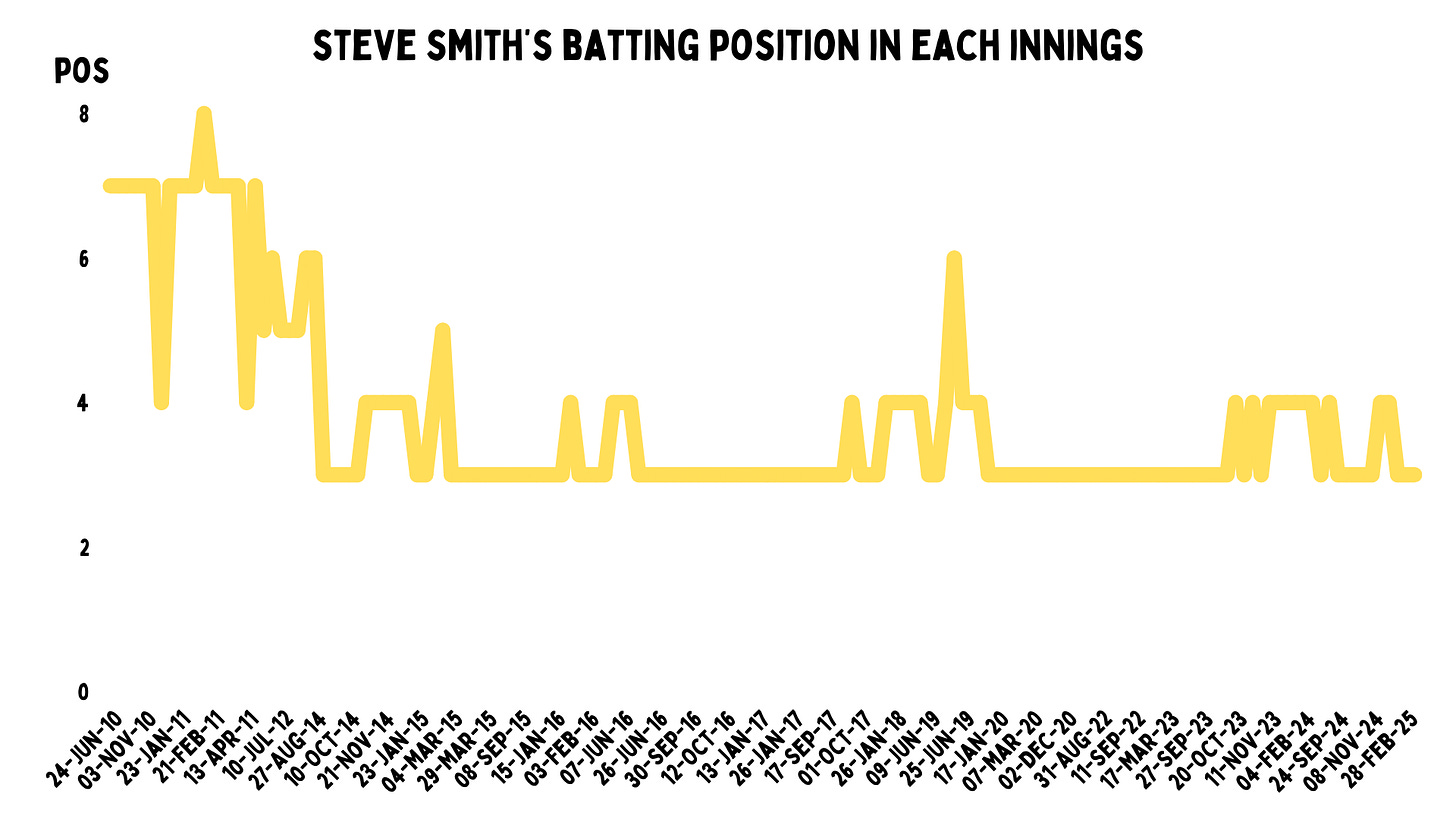

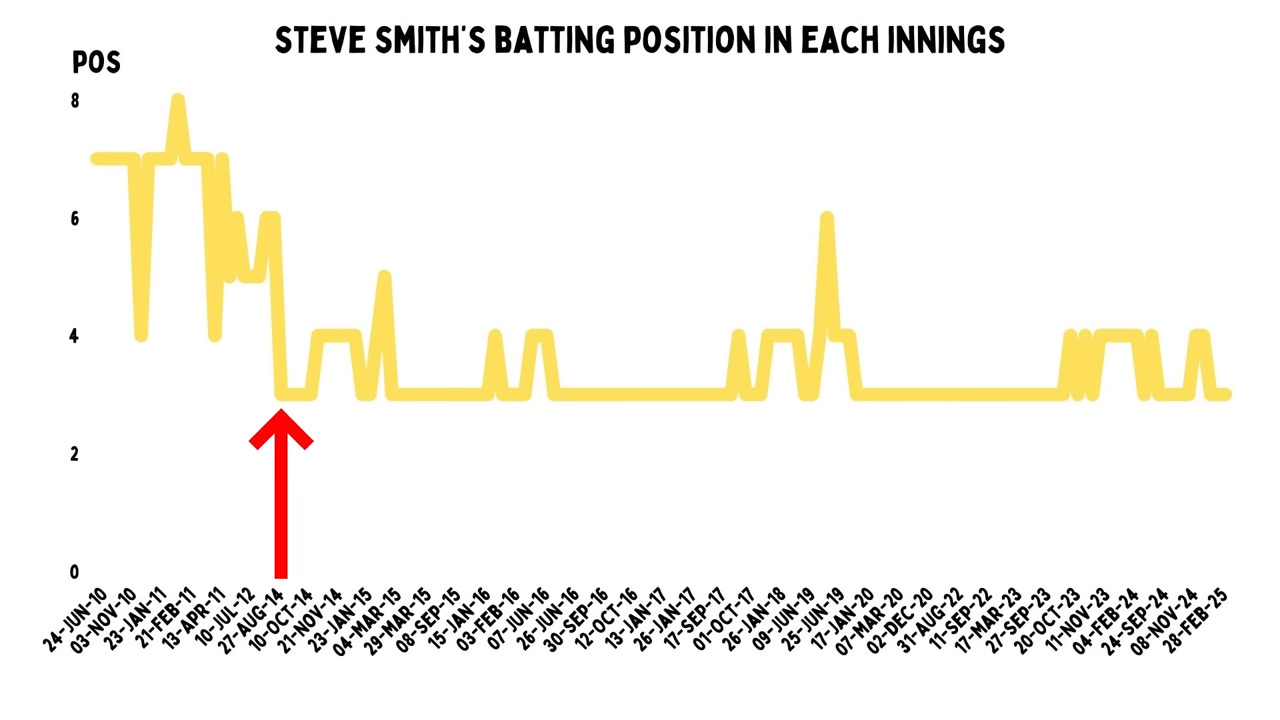

Steve Smith made his ODI debut all the way back in February 2010 at the tender age of 20. He was drafted into the first team primarily for his ability to bowl wrist spin, and was pencilled in to bat in the lower order. This was exactly like Tests. He was also a brilliant fielder, making him a great young prospect.

In his first 25 innings, he managed 431 runs at an average of 21 and a strike rate of 91, with no fifties or hundreds. And 15 of those knocks came at number seven. For casual fans, Steve Smith was a mere Shane Warne impersonator who could bat a bit. Not many knew that he was a full-time batter in junior cricket. Many of his early highlights in the Big Bash or at the international level were fielding.

He changed those perceptions after he was promoted to bat at three versus South Africa in September 2014. In the next nine innings he played that year, he scored 490 runs, including two tons and three fifties. This was actually after his breakthrough in Tests, so even with all those runs coming in, Australia were not sure about him in his format.

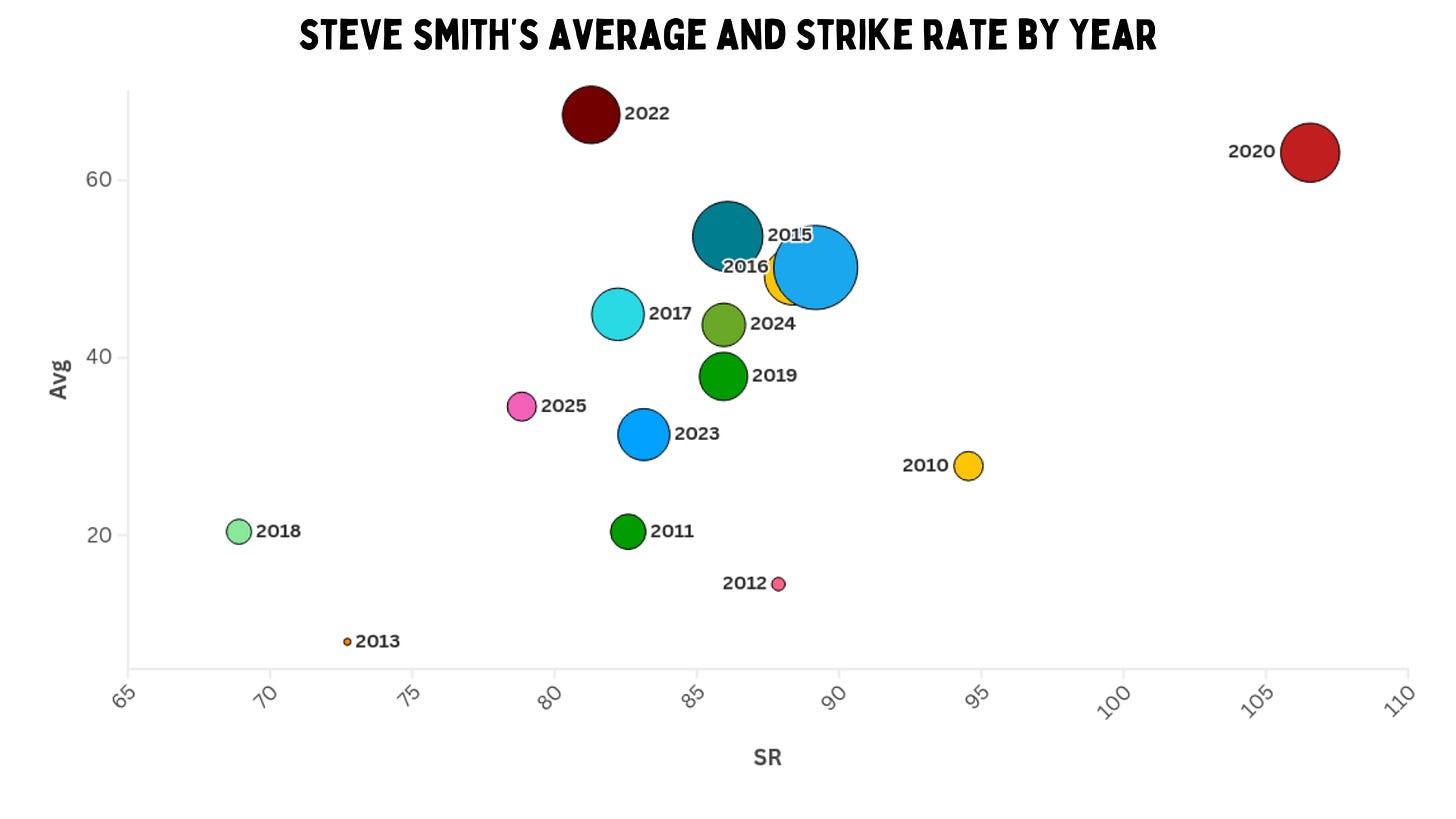

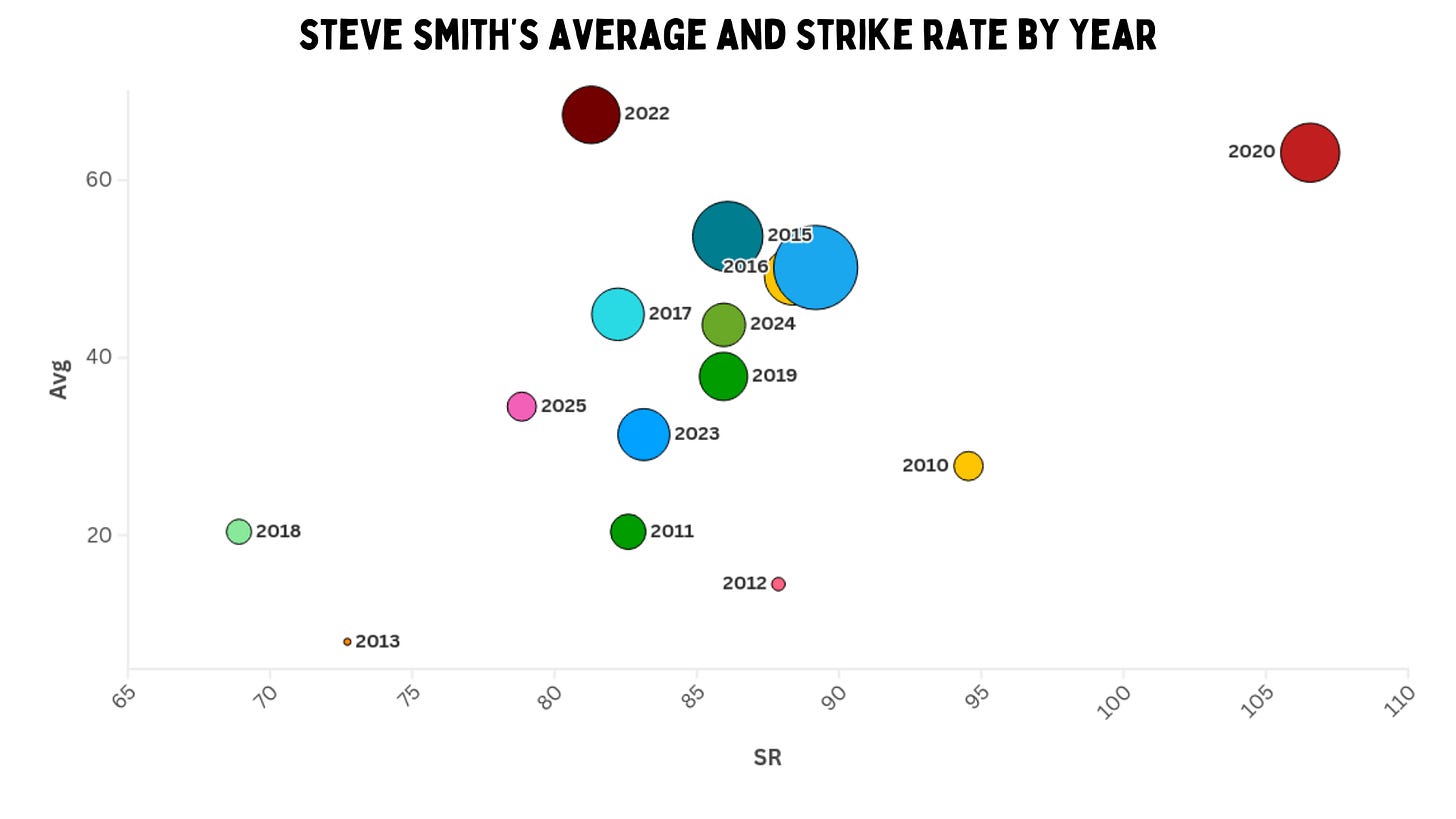

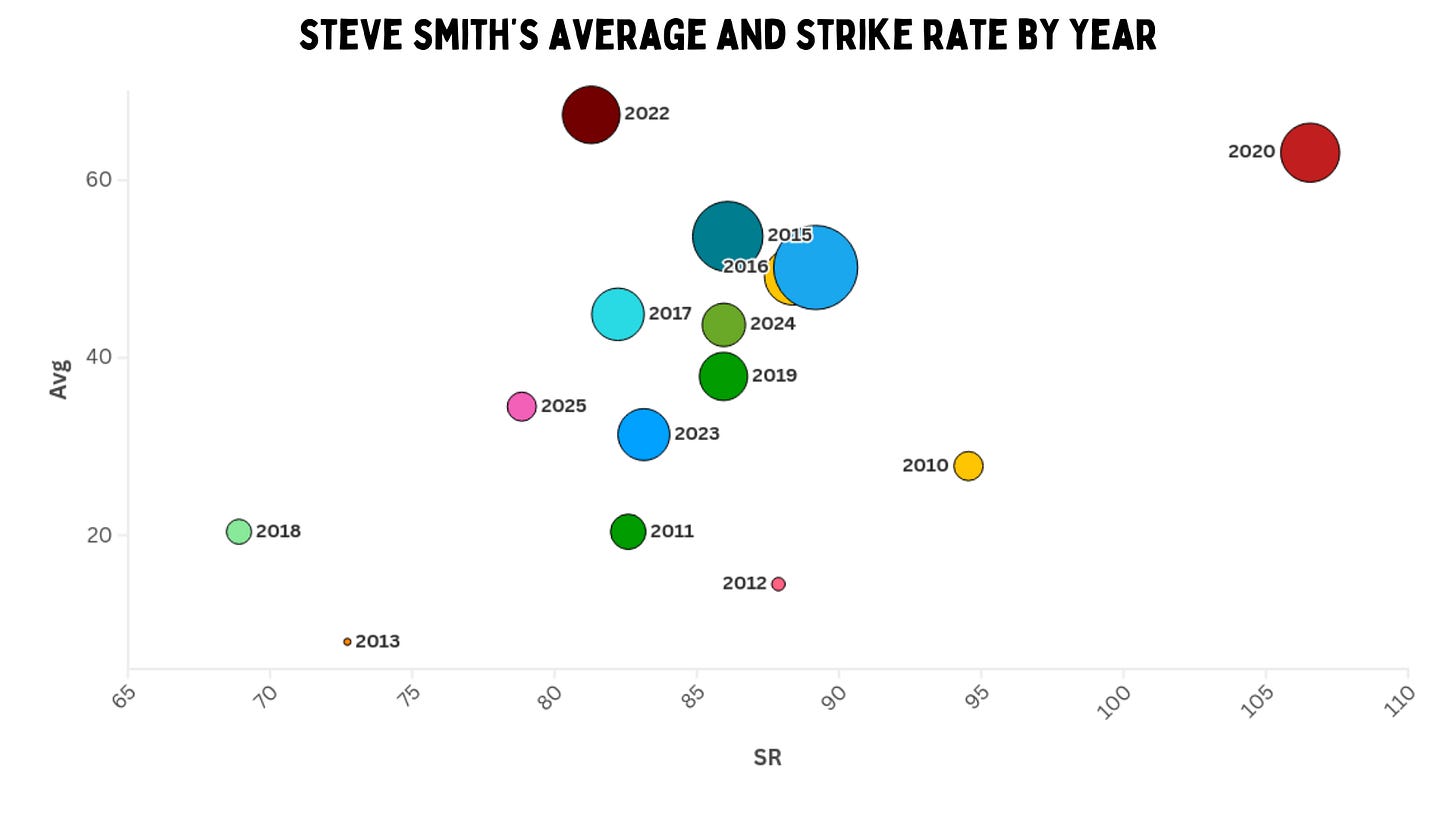

In the two years that followed, Smith averaged north of 50 and added 5 more tons, while also lifting a World Cup on home soil. At this point, ODIs kind of suited him as you couldn’t get him out. It was before the middle overs scoring revolution, and he could do his thing without anyone complaining. His batting average dropped to below 45 in 2017, 20 the year after (when he was out of the team due to Sandpapergate), and just under 38 in 2019, another World Cup year.

At times, it was unsure how much he cared for ODIs as well. In Tests, it looked like he wanted to bat forever; you never got that feeling in the 50-over game.

But in 2020, something seemed to inspire him. He averaged 63 and struck at over 106. Two back-to-back 62-ball tons against India were at the forefront of his worldie year, and they were scored against an attack featuring both Jasprit Bumrah and Mohammed Shami. For a player who often plodded through, he seemed to have found a real purpose and style. But weirdly, that was it. 2020 remains the only year he scored at more than run a ball.

In 2022, he had his best average in a calendar year, four more runs per dismissal than 2020, but his strike rate dropped to 81. Did he lose his scoring ability to Covid in 2021? Because it looked like he was unlocking something special, and since then he’s gone back to solid accumulation.

A natural regression followed, and he never scored another hundred in the format.

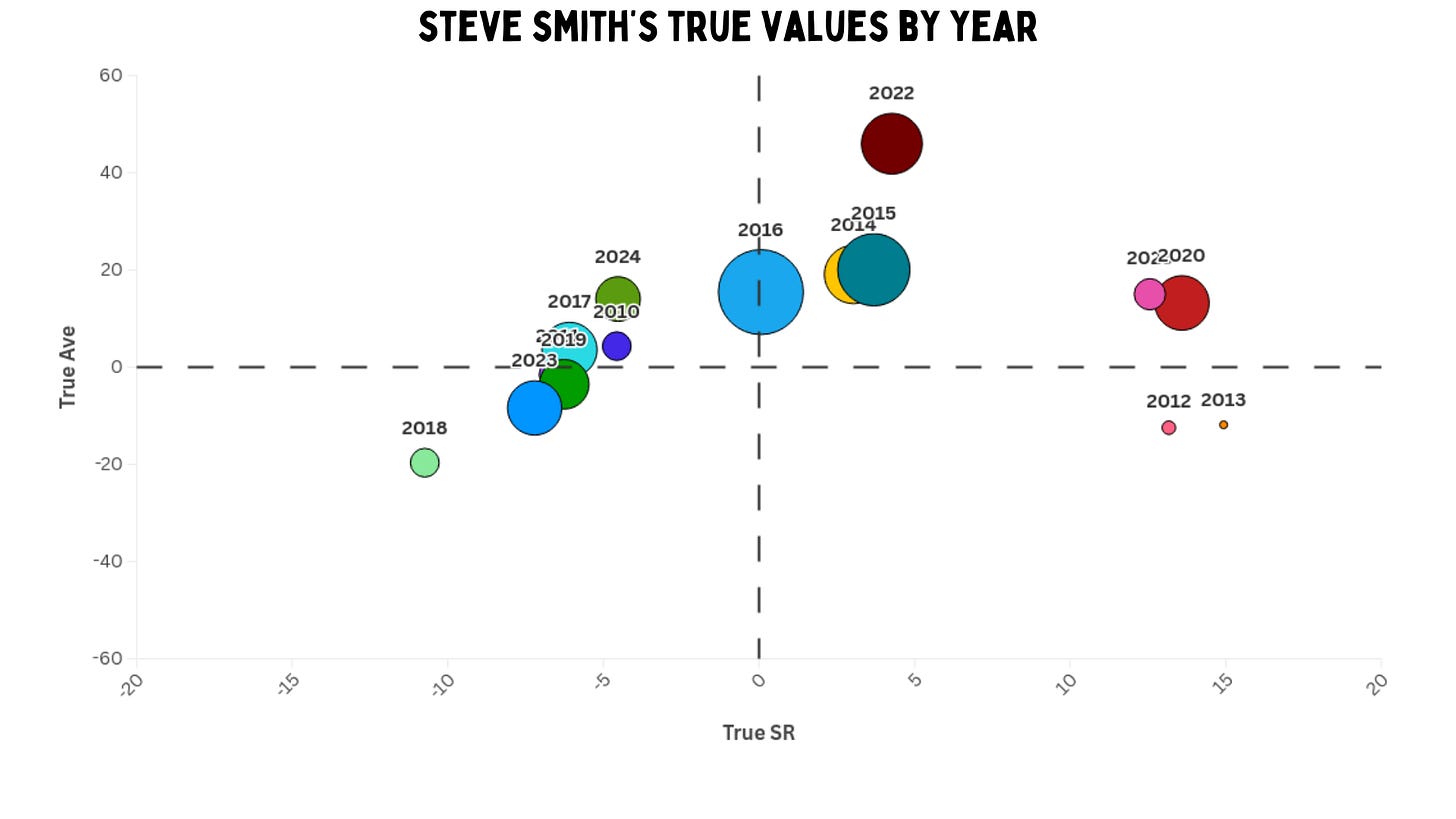

The true values paint a similar picture. From 2014 to 2016, his true averages were in the 15 to 20 range, at a neutral or positive true strike rate. He had a faster scoring year in 2020, with a true average and true strike rate around 13, while 2022 was one where he had a true average of 46 and a true strike of 4.

However, he left a lot to be desired on either side of these years. That really sums up his ODI career: you think he’s hitting his ODI peak, but that streak doesn't carry on.

Interestingly though, his true values this year have been close to that in 2020. He’s only played five innings, of which three were in Colombo (RPS) and Dubai. Because of that, the expected average and strike rate would have been lesser than normal.

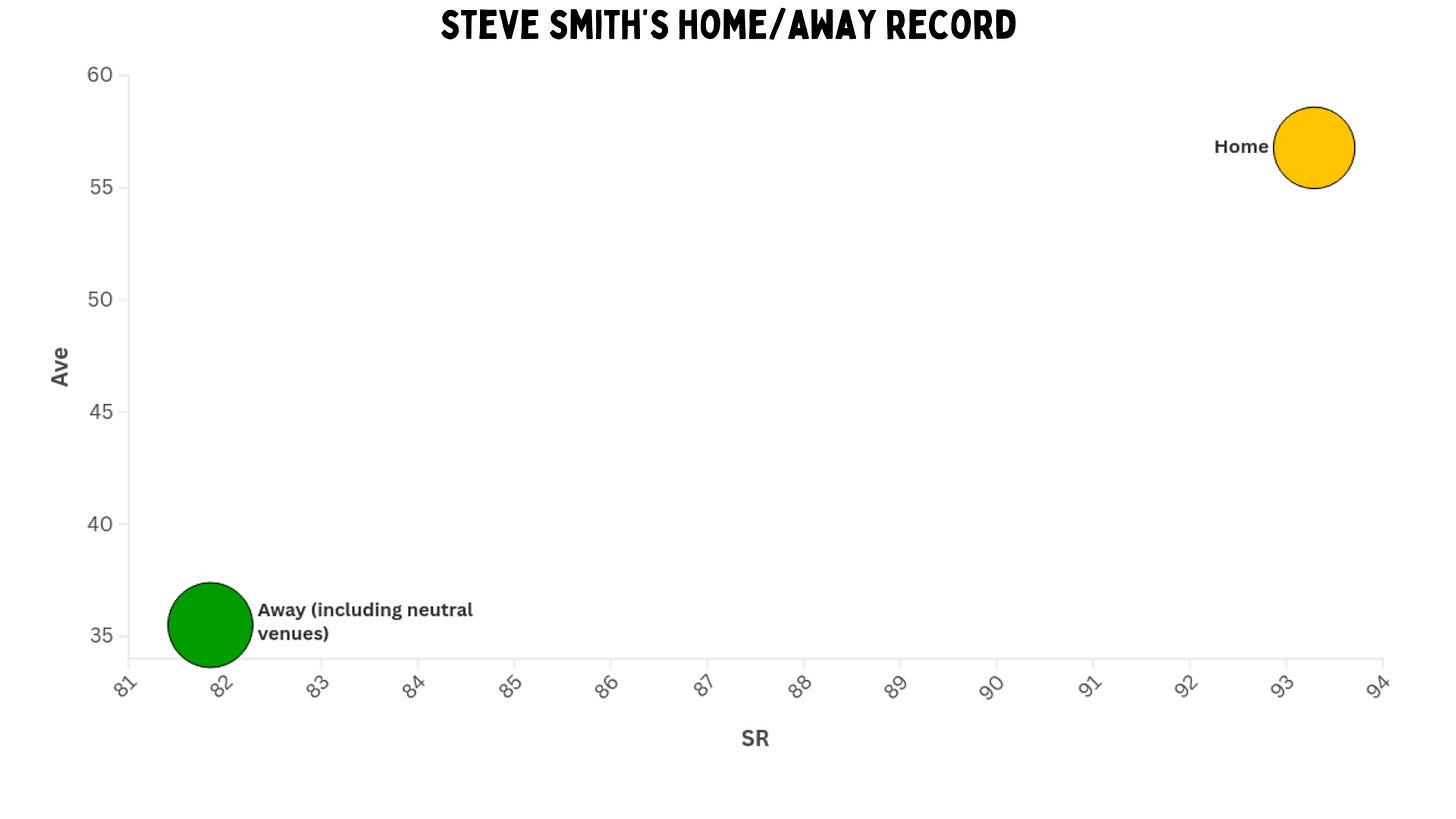

Was Smith a home track bully? It's a statement that obviously doesn’t hold true in Test cricket, but ODIs paint a different picture. In Australia, he batted 60 times, at an average of just under 57, and a strike rate of 93-plus. Most of his greatest work is at home, with nine of his 12 ODI tons. Away from home, he averaged in the mid 30s, striking in the low 80s, which is mediocre by the most lenient of benchmarks.

At home his numbers would have him as a GOAT, away he’s a struggling role player. It’s weird, because there isn’t a great reason for this with his talent.

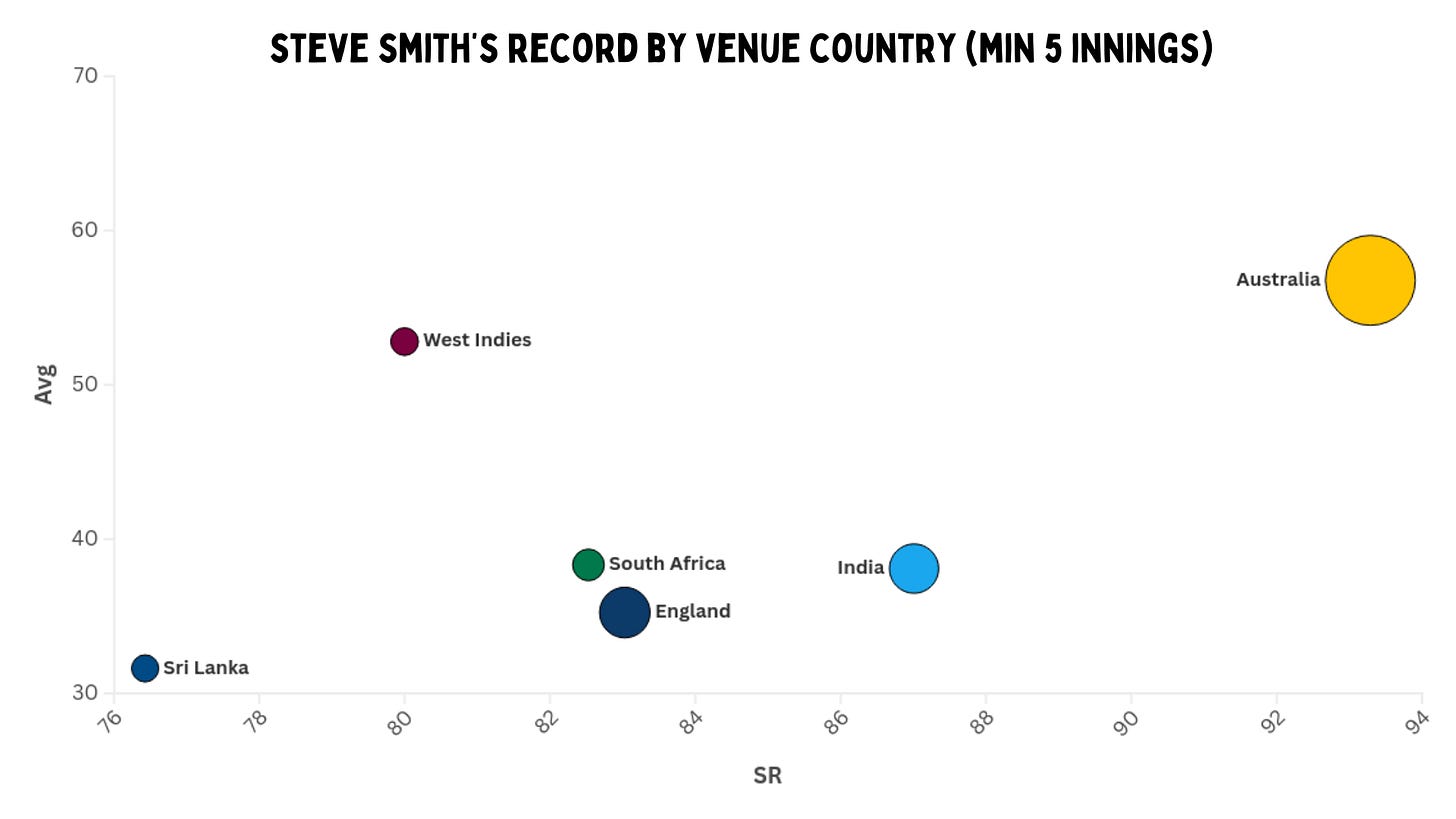

The only countries where he averaged over 50 apart from Australia were in the UAE (263 runs in four innings at an average of 65.75 and a strike rate of 78.74) and the Caribbean, spanning a grand total of 10 innings combined. Beyond those regions, Smith couldn’t manage an ODI batting average of 40 in any country across the globe, which is below par.

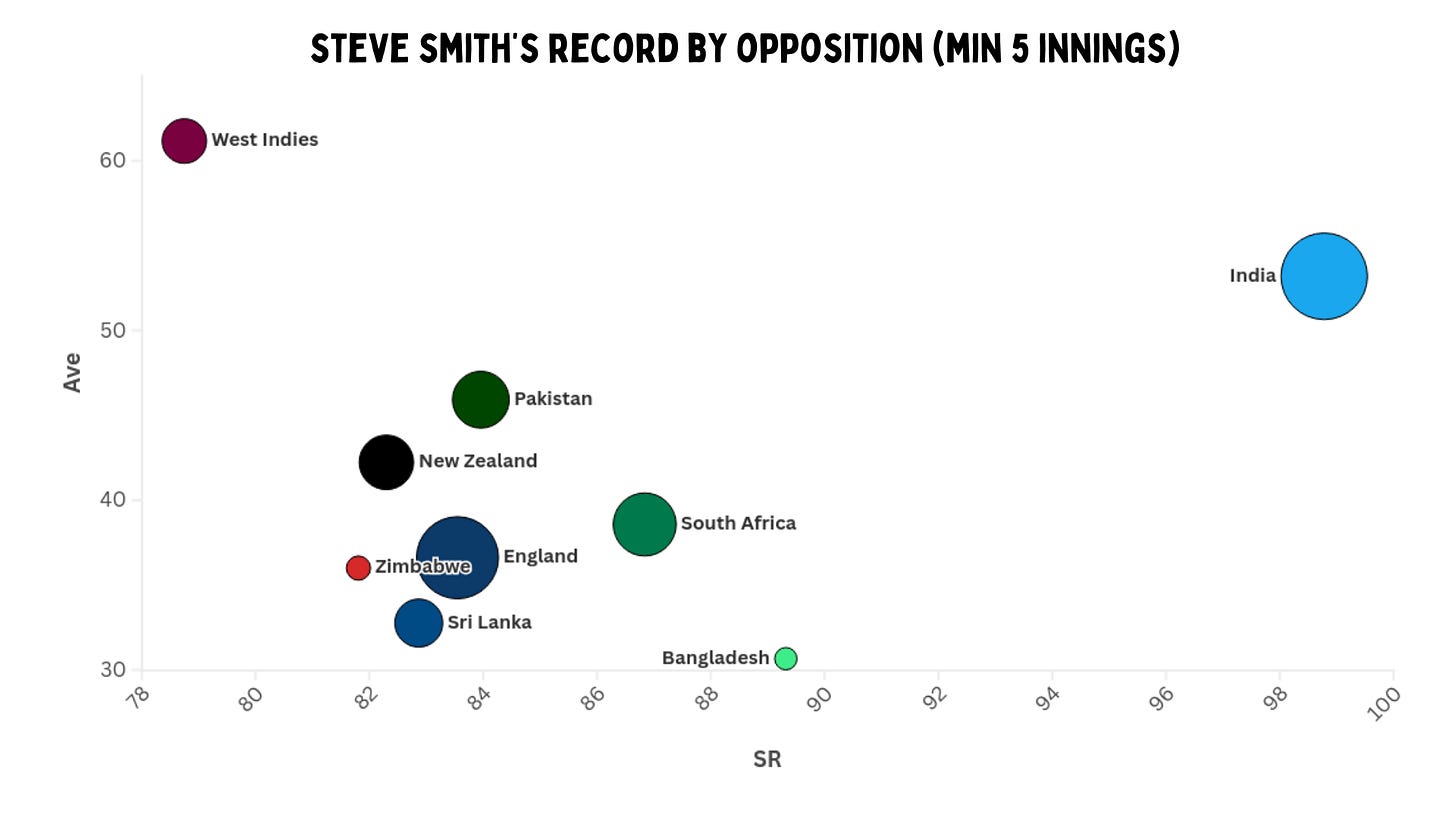

How about Smith’s record against different opposition teams then? Unsurprisingly, his record versus India is spectacular. He averages nearly 59 against them in Tests, and just five runs less per dismissal in ODIs. Five of his 12 tons have come vs India, one of which was in a World Cup semi-final, that Australia won. And remember, an all-time great performance in the Border-Gavaskar Trophy preceded that World Cup triumph.

Without wanting to bring up his nocturnal habits in Tests, it did at times feel like he sleepwalked through 50-over cricket. But perhaps the challenge of India’s bowling woke him.

Amongst teams against whom Smith has batted against in a minimum of five innings, he has averaged most versus the West Indies, with 61 runs per dismissal at a strike rate of 79, but in eight innings only, with no hundreds.

He has done alright versus Pakistan and New Zealand, averaging in the mid to low 40s, but his average slips to less than 40 against the remaining five teams.

An India specialist, without doubt, but somewhat unremarkable against the rest.

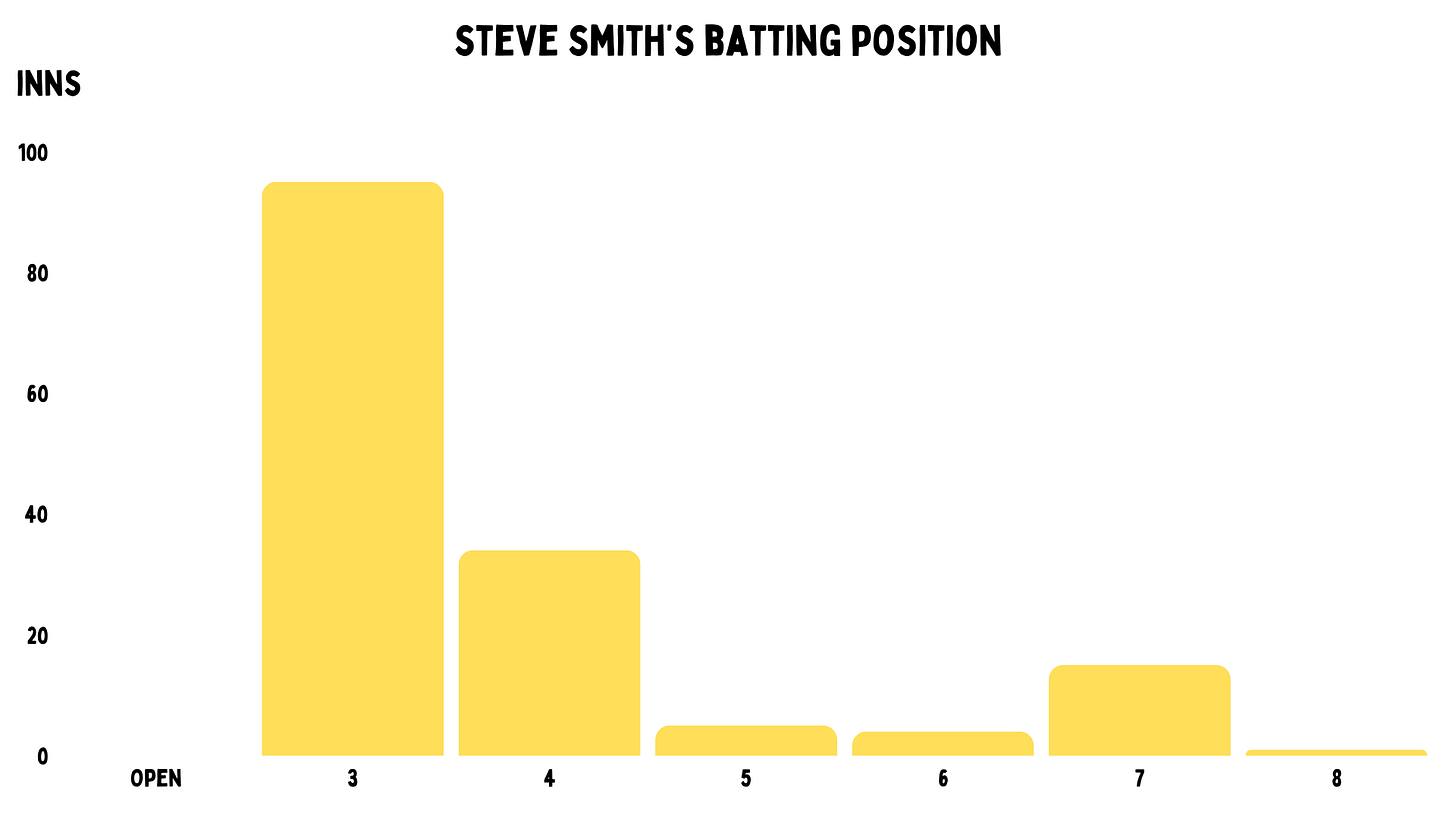

You could argue that the fact that Smith has batted in every position from number 3 to 8 in ODIs has impacted his overall stats. But he was also really a three (or four when World Cups came around) for a long time.

95 of his 154 innings have come at number 3, where he has been prolific – 4369 runs at an average of 52 and a strike rate of 86. Still a little slow, but at least the average is Smith-like.

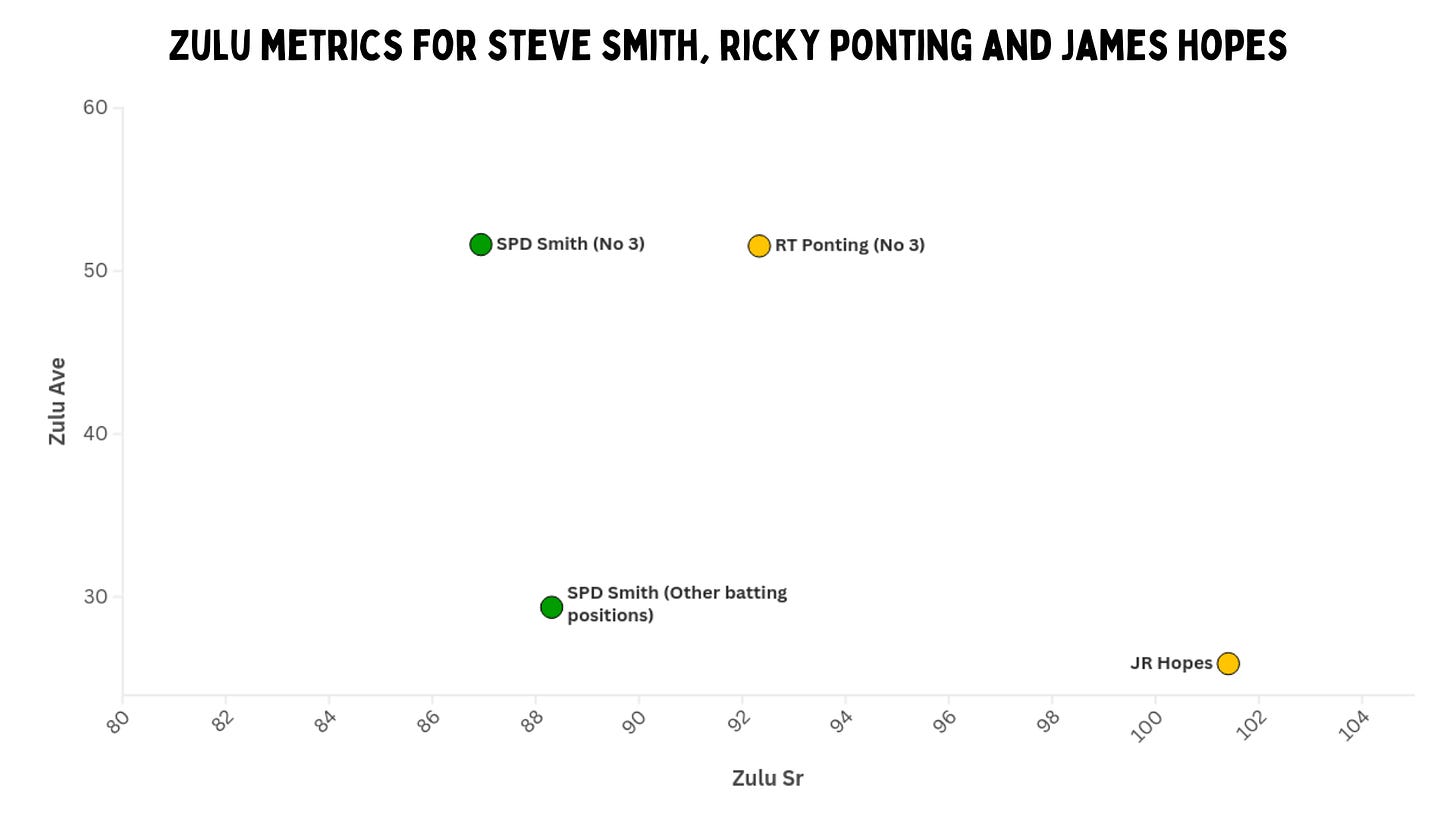

At first drop, he has hit 11 of his 12 centuries and 27 of his 35 fifties. Everywhere else in the batting order, he averaged 29 at a strike rate of 89. That’s a bit like comparing Ricky Ponting to James Hopes.

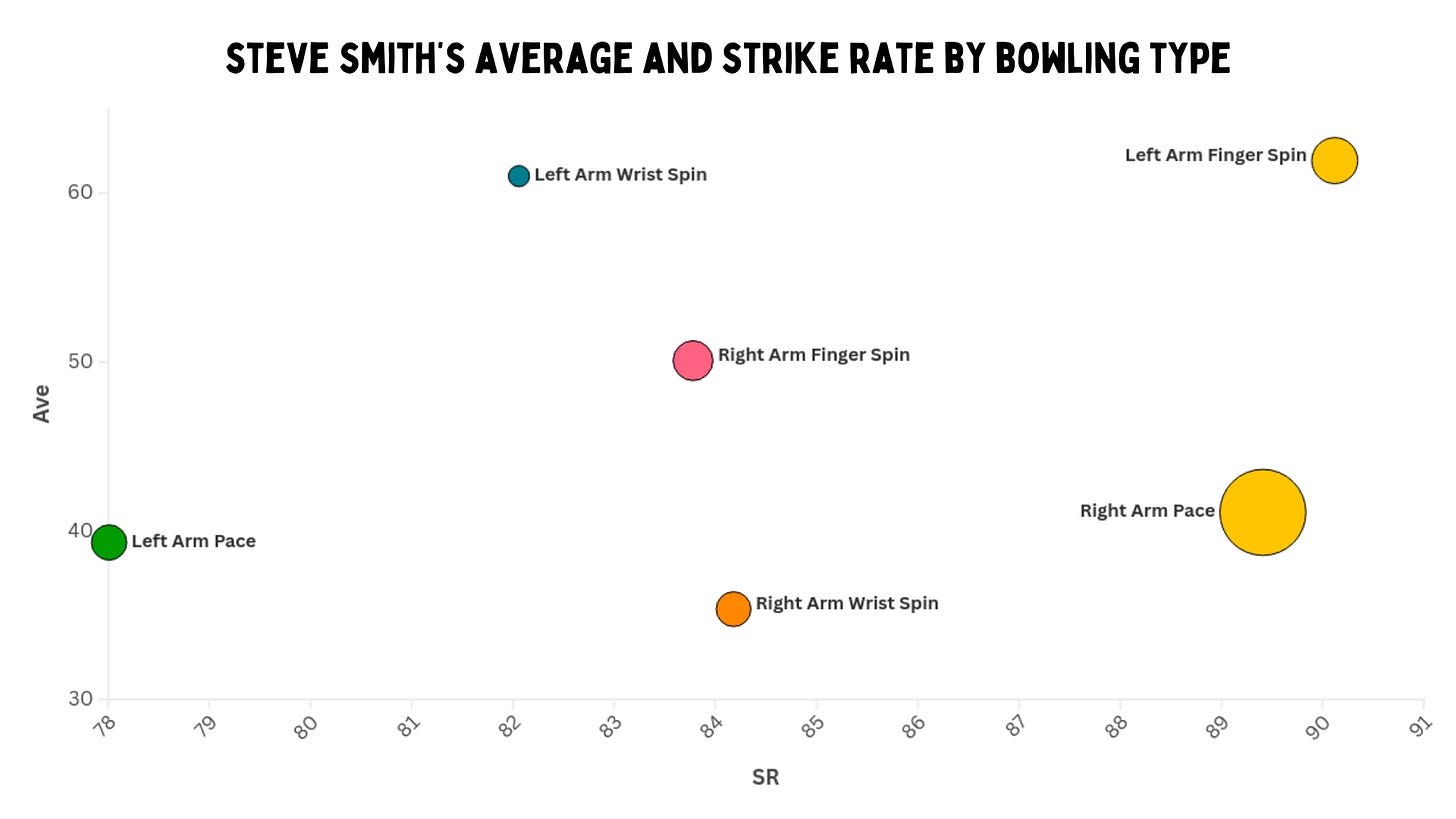

Was there a specific bowling type that Smith struggled against in 50-over cricket?

He averaged below 40 against left-arm pace and right-arm wrist spin, striking at only 78 and 84 respectively. He had high averages versus left-arm wrist spinners and right-arm offies, but at a strike rate in the low 80s. Compared to left-arm quicks, he was significantly better when we went up against right-arm pacers – averaging 41 and striking at nearly 90. His best record came against left-arm finger spin.

In Tests, SLA can trouble him, here he smashes them. His ODI self is only distantly related to his Test version.

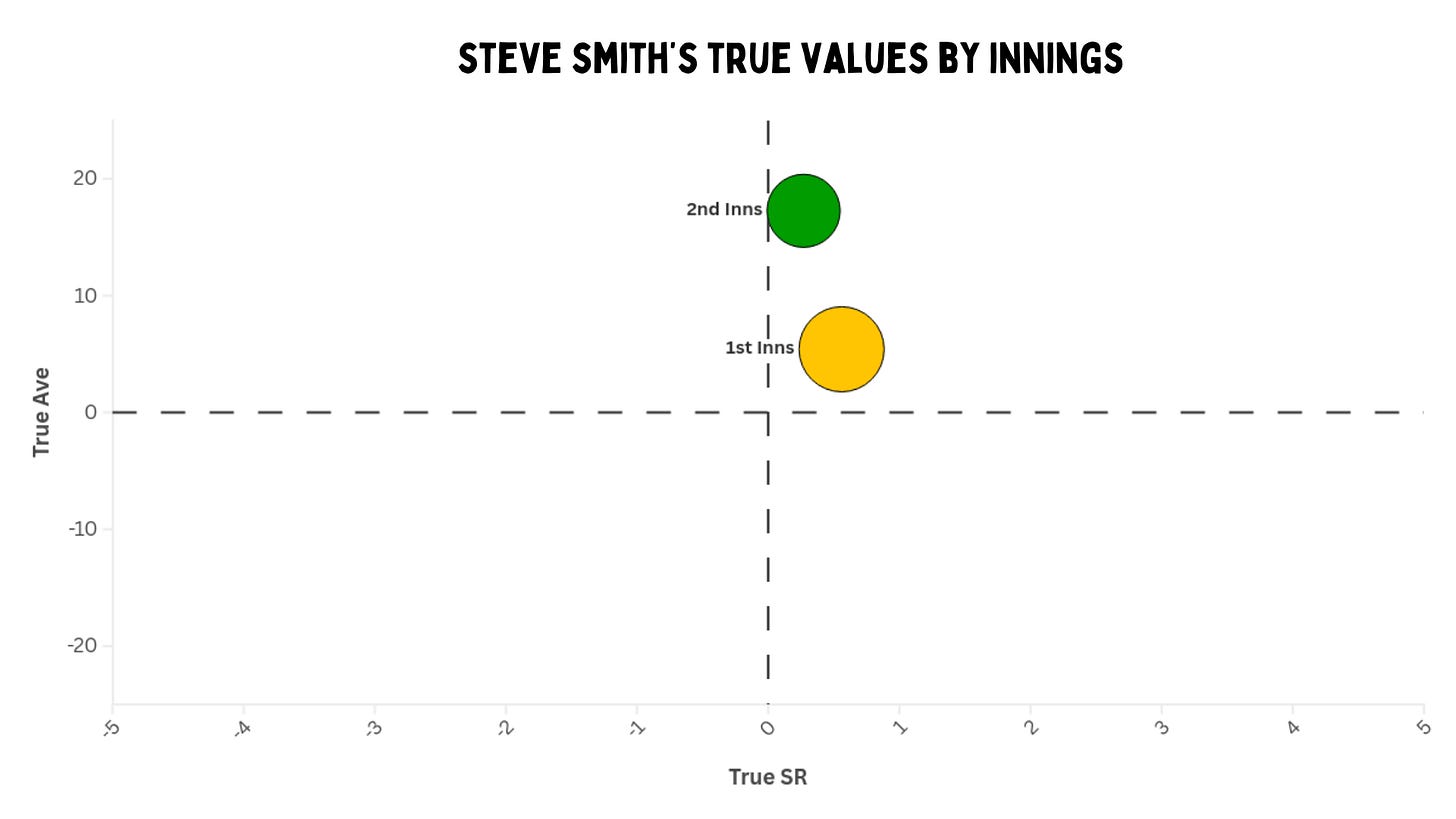

Smith has a slightly better true strike rate in the first innings, but there is a significant difference in the true averages. In ODIs, he seems to prefer batting when he knows the target. Again, this doesn’t really follow the pattern. We’ve seen that he is incredible in the first innings of a Test match, and not so much in the fourth. Even in T20s, he has a superior record batting first.

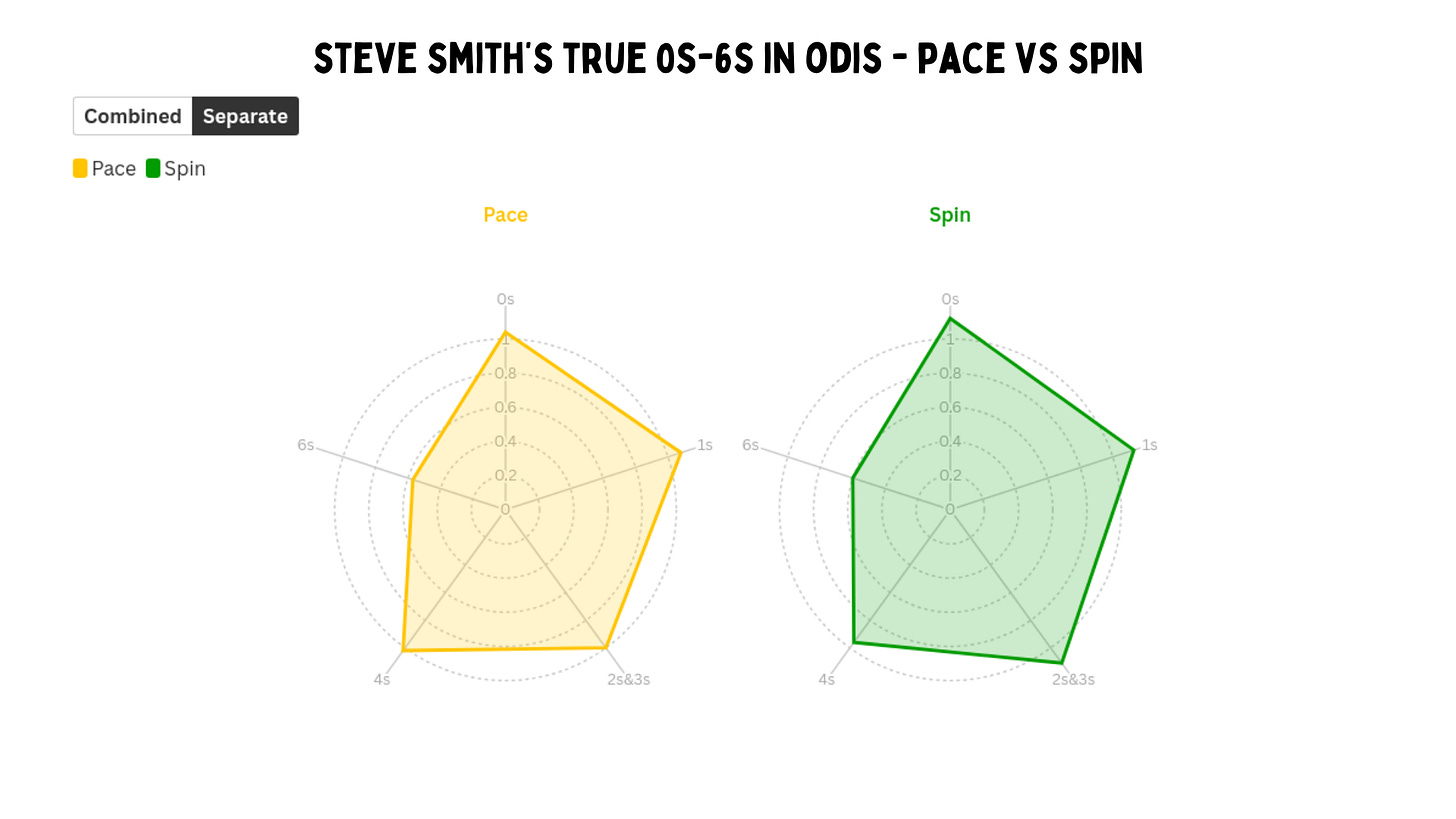

True 0s to 6s help us figure out the profile of a batter with respect to the overs they bat in. Smith is a lot better at rotating strike against spin than pace, and he also faces fewer dot balls than expected versus the slower bowlers. But he scores more fours than par against the quicks, and isn’t really much of a six-hitter against either bowling type.

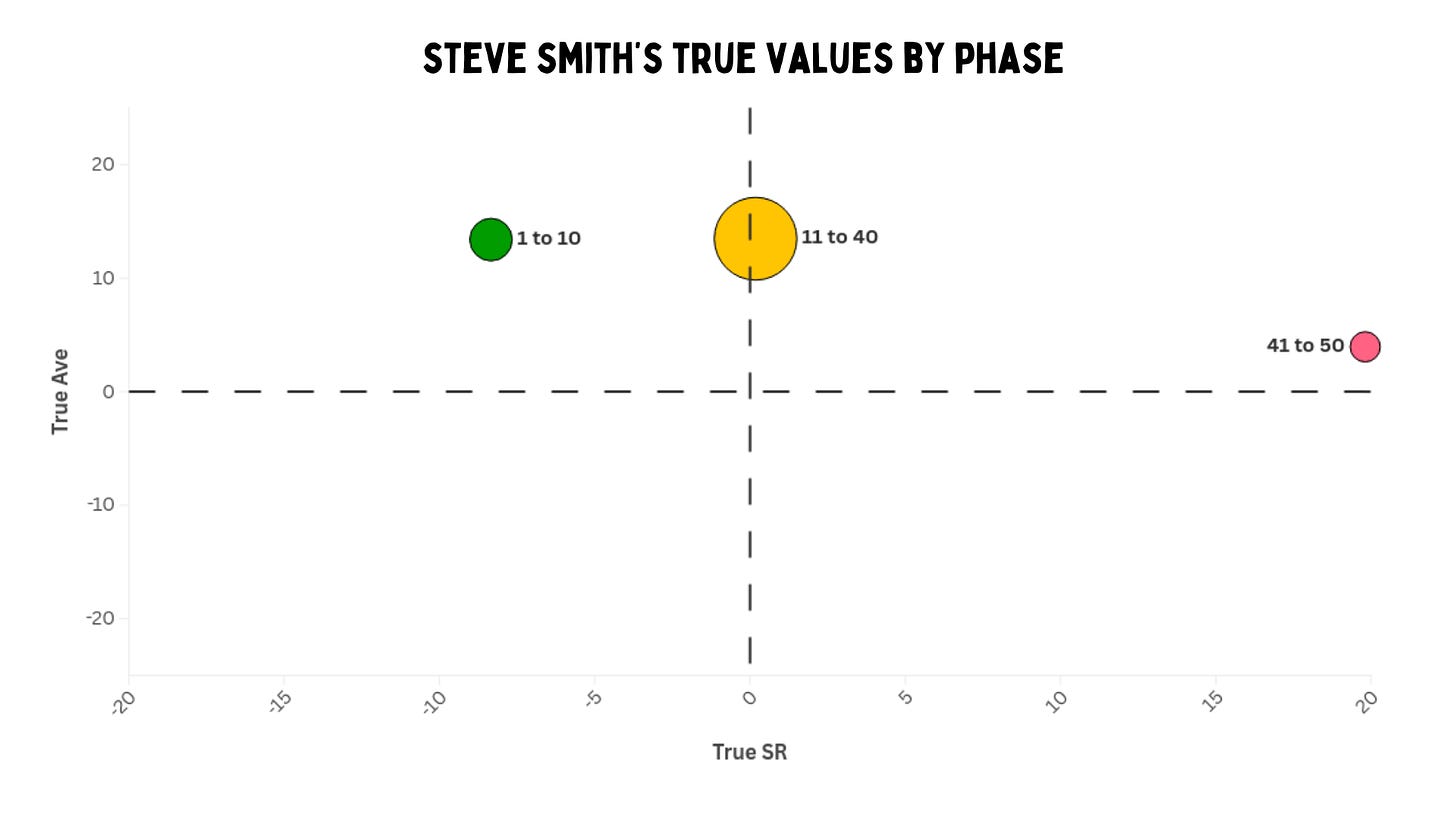

Smith’s template is pretty clear: look to stay in during the powerplay, consistently knock it around in the middle, and smash the ball at the death. In the first ten overs, he has a true average of 13, and a true strike rate of about 8 less than expected. Naturally, most of his runs have come between overs 11 to 40, where he has a similar true average, but a par true strike rate. He strikes at nearly 20 more than expected at a true average of about 4 in the final 10 overs.

It is one of the more fascinating things about him, that he can really accelerate when he wants too. But in ODIs or T20s, he often doesn’t seem that interested in scoring fast.

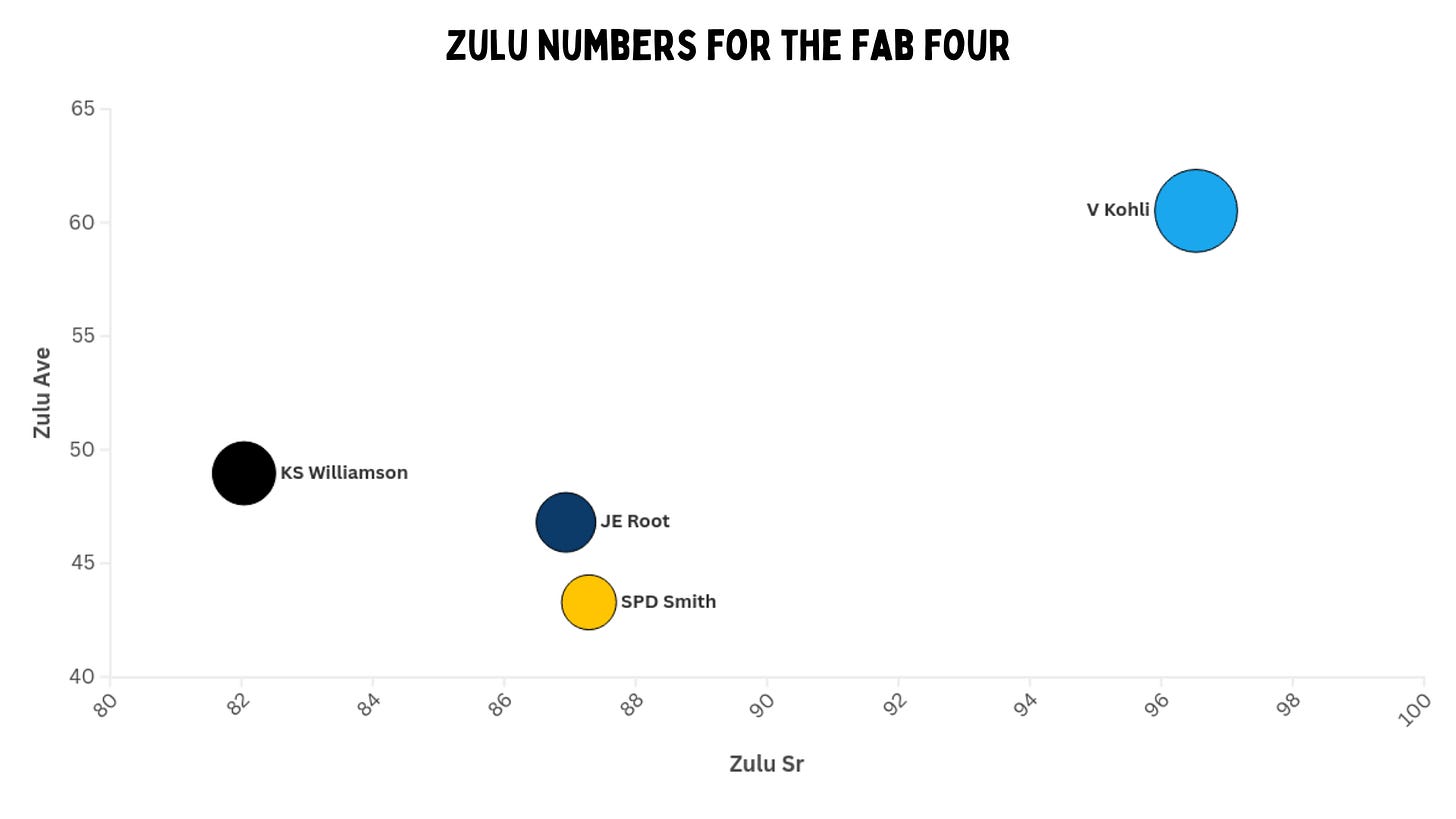

The Fab Four is a Test cricket concept, but they all perform a similar role in 50-overs cricket as well. Of course, Virat Kohli is in a different league, but it’s intriguing how there isn’t much between the other three.

Smith’s strike rate is similar to that of Joe Root, which is around 87. Kane Williamson averages 49, but is close to five points behind them on strike rate. Root has made more than 2000 extra runs as well. But even so, their numbers aren’t that dissimilar. Yet Root is talked about as an ODI player an awful lot more than Smith.

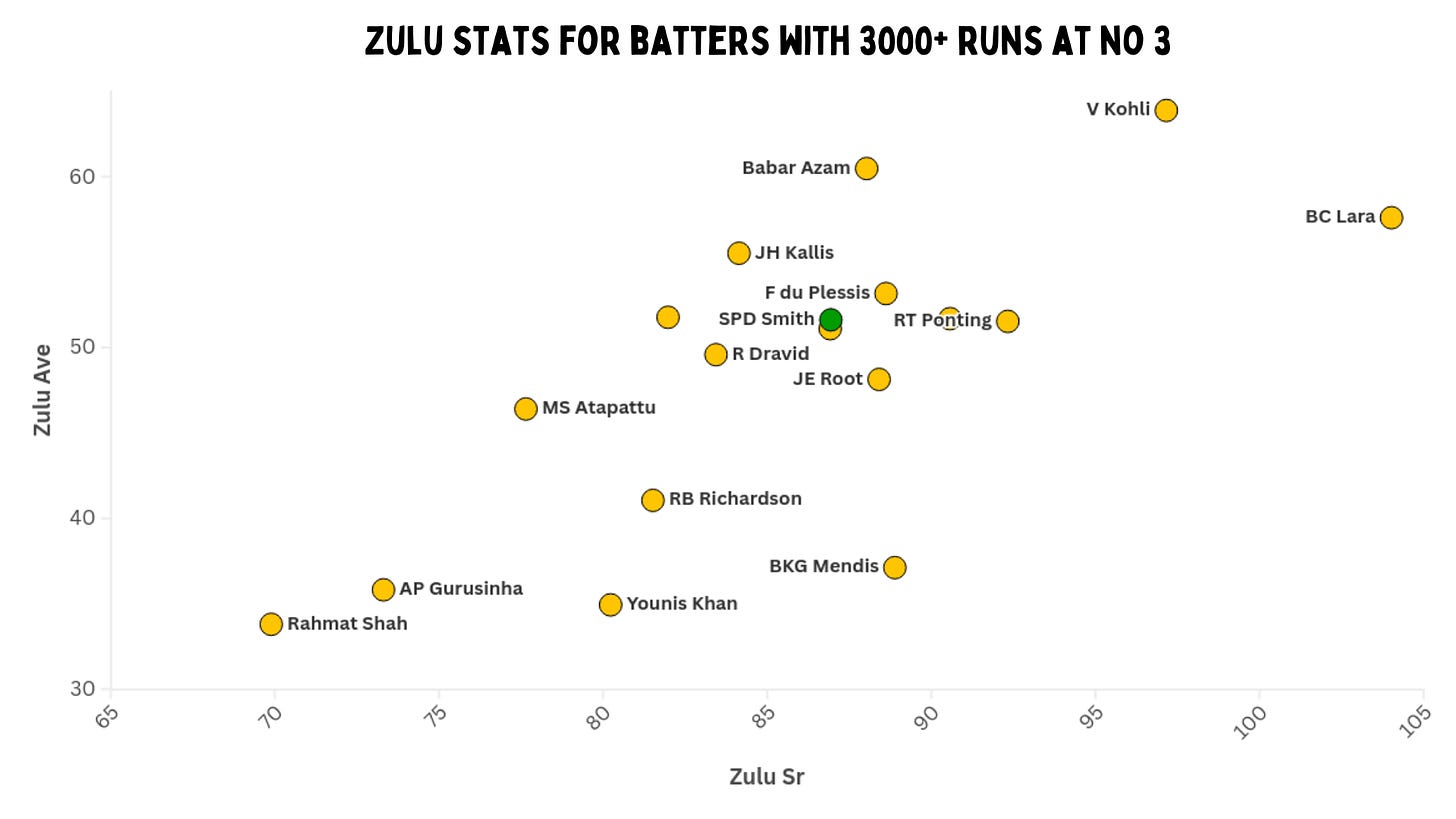

But remember how we talked about Smith batting everywhere in the batting order? So how do his numbers compare with number three batters with 3000 or more runs in ODI history?

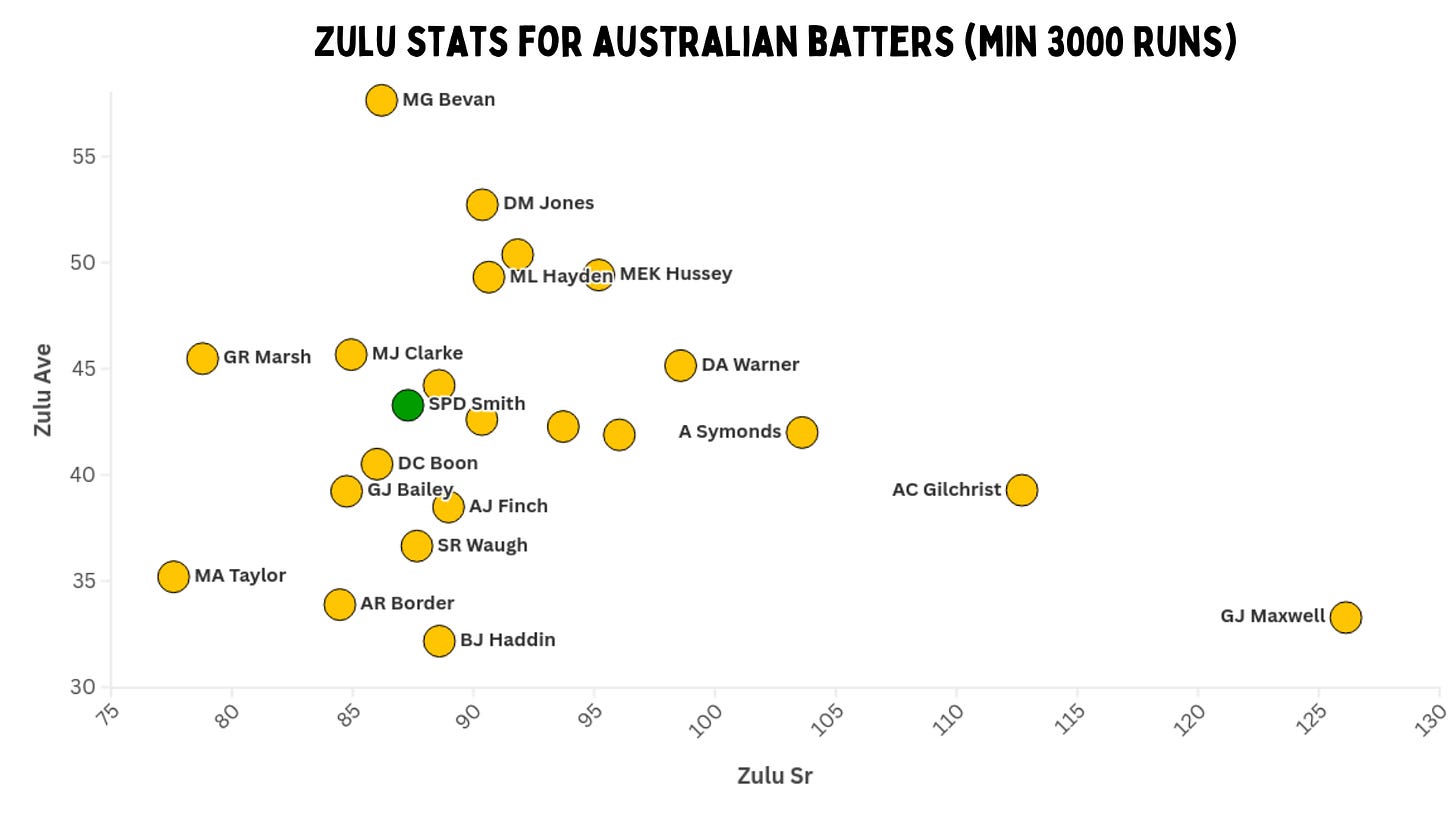

Smith’s average now jumps up to 51, and his nearest neighbour on this graph is Kumar Sangakkara. You can see him a bit behind the first two great number threes from Australia, Dean Jones and Ponting. But I think this is a true representation of who he is as an ODI player. His early career numbers ruin his record, and he never quite worked out how to bat at four. But as a three, his average is comparable to that of Williamson, at a quicker scoring rate. Root averages 48 at a strike rate of 87 at number three, according to the Zulu metrics.

Each of these three batters have also had memorable World Cup campaigns: Smith in 2015, Root and Williamson in 2019.

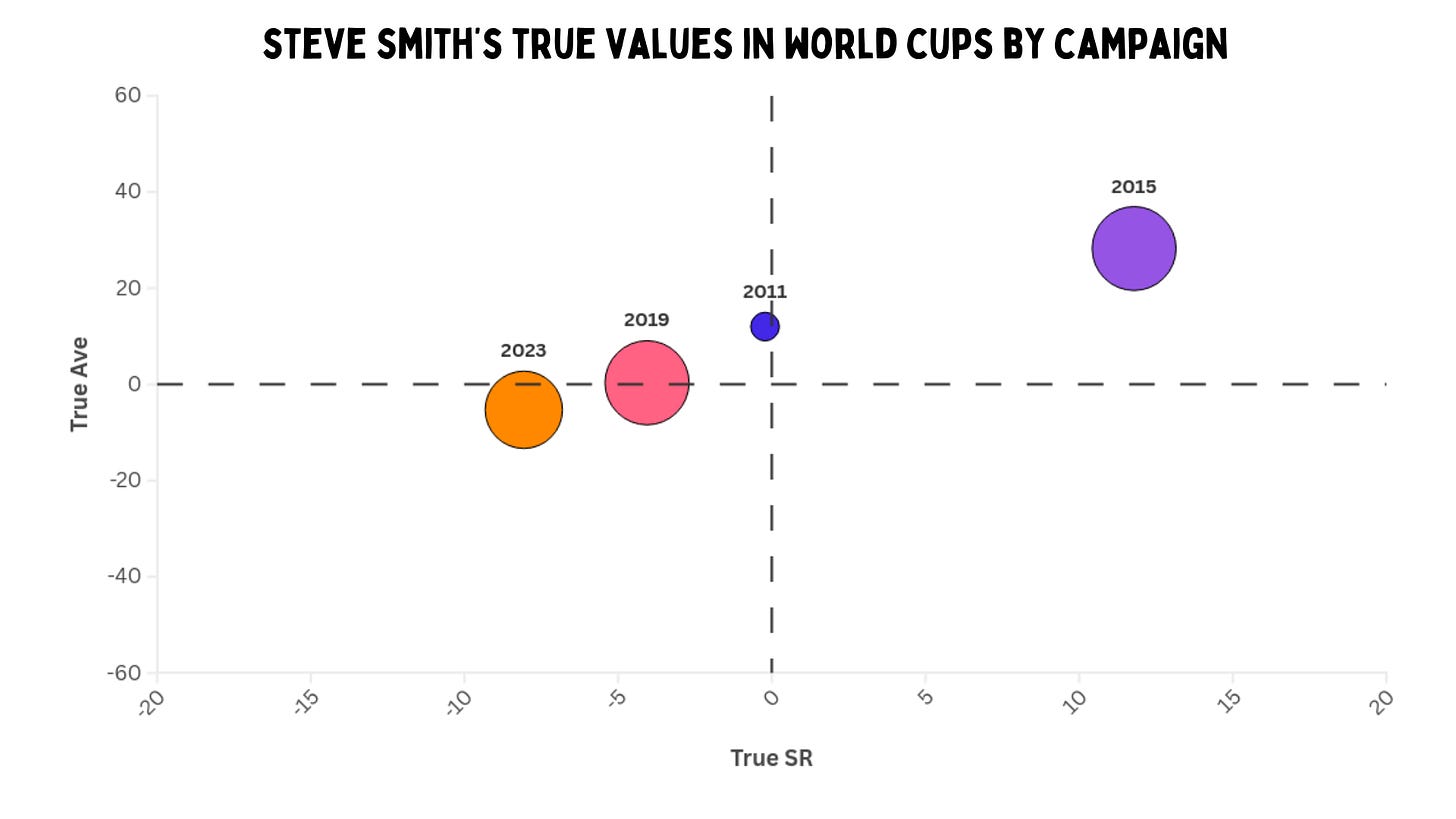

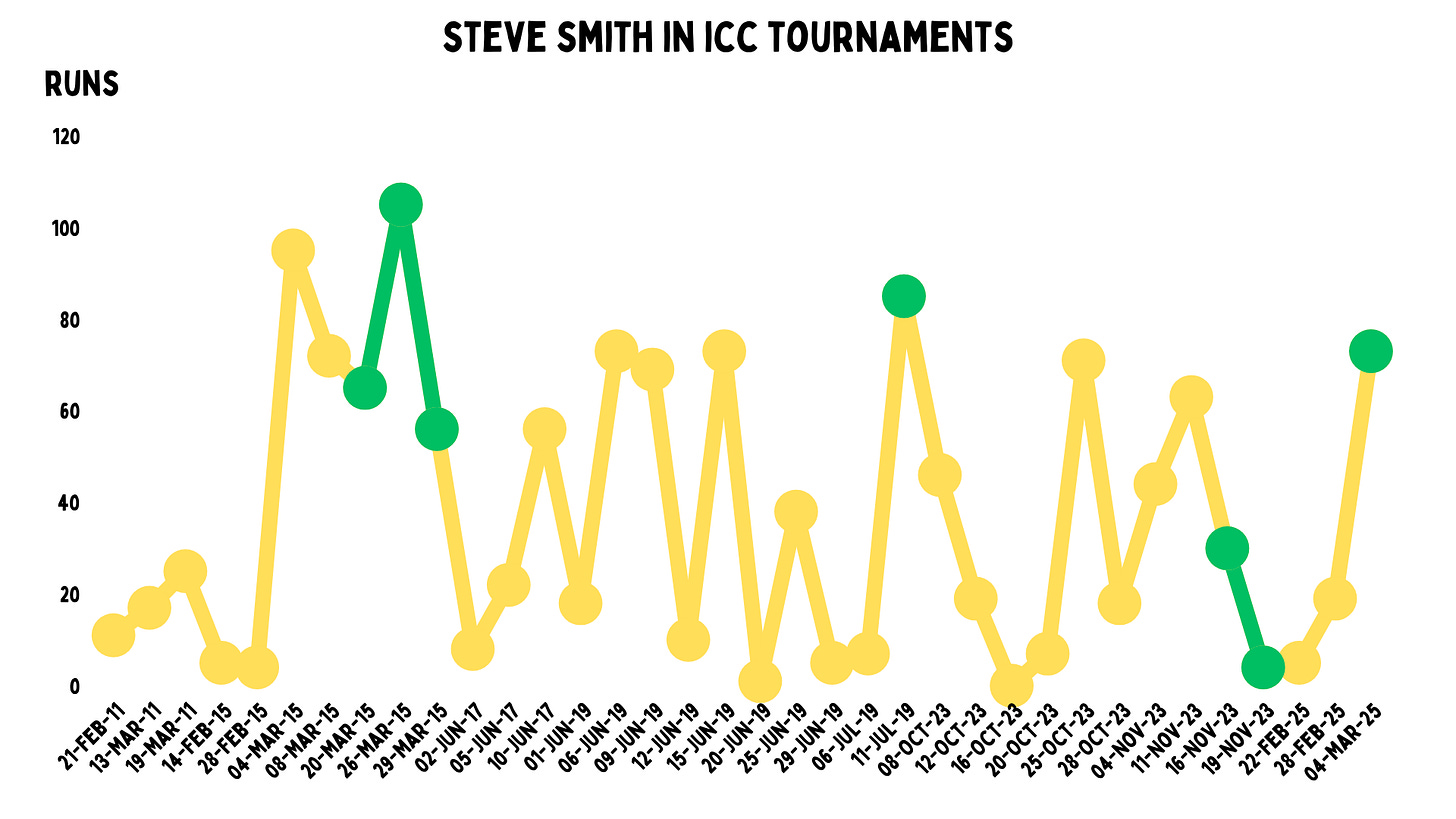

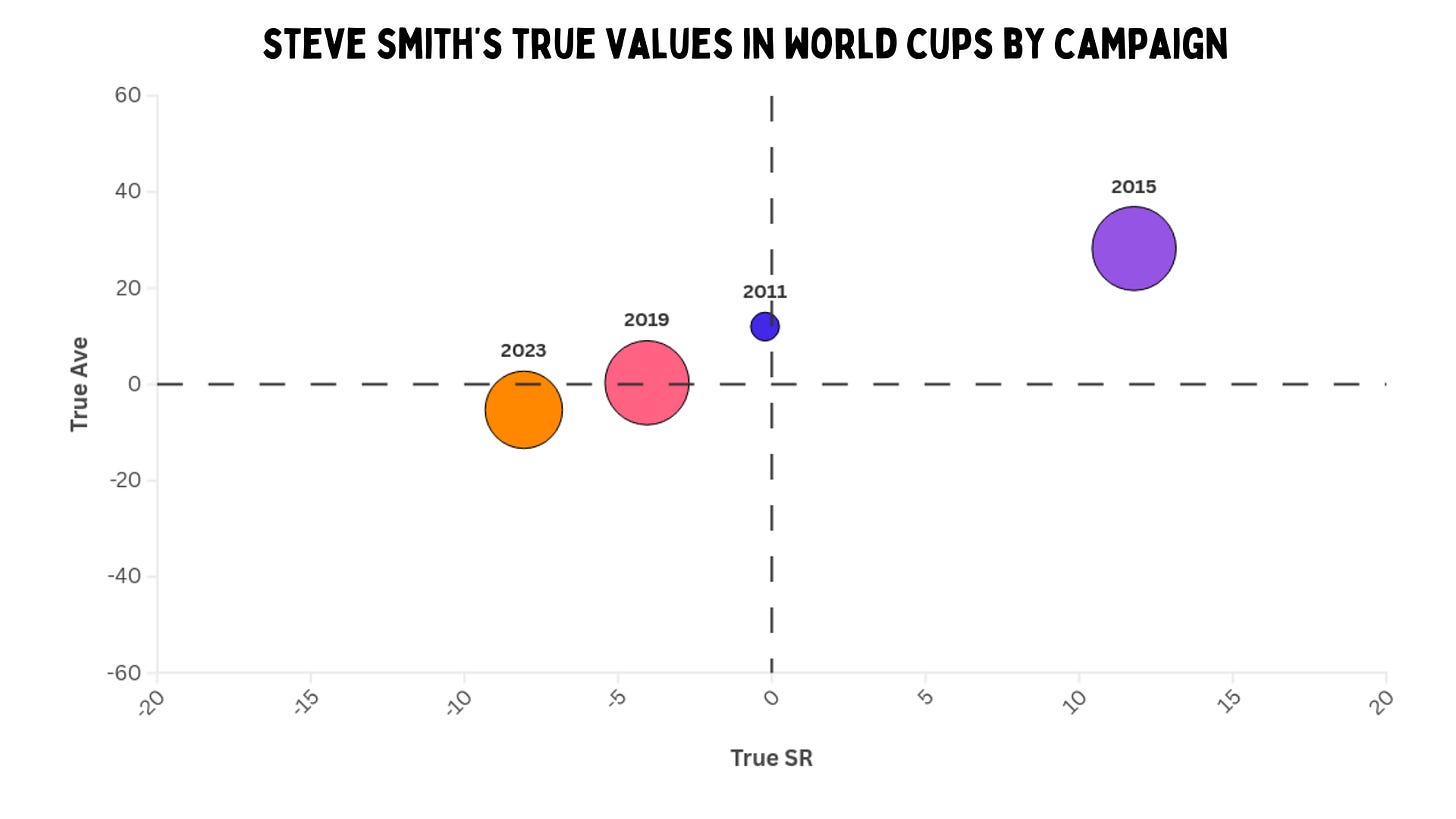

When Smith won his first World Cup with Australia, he scored 402 runs at a true average of 28 and a true strike rate of 12. Those are incredible numbers.

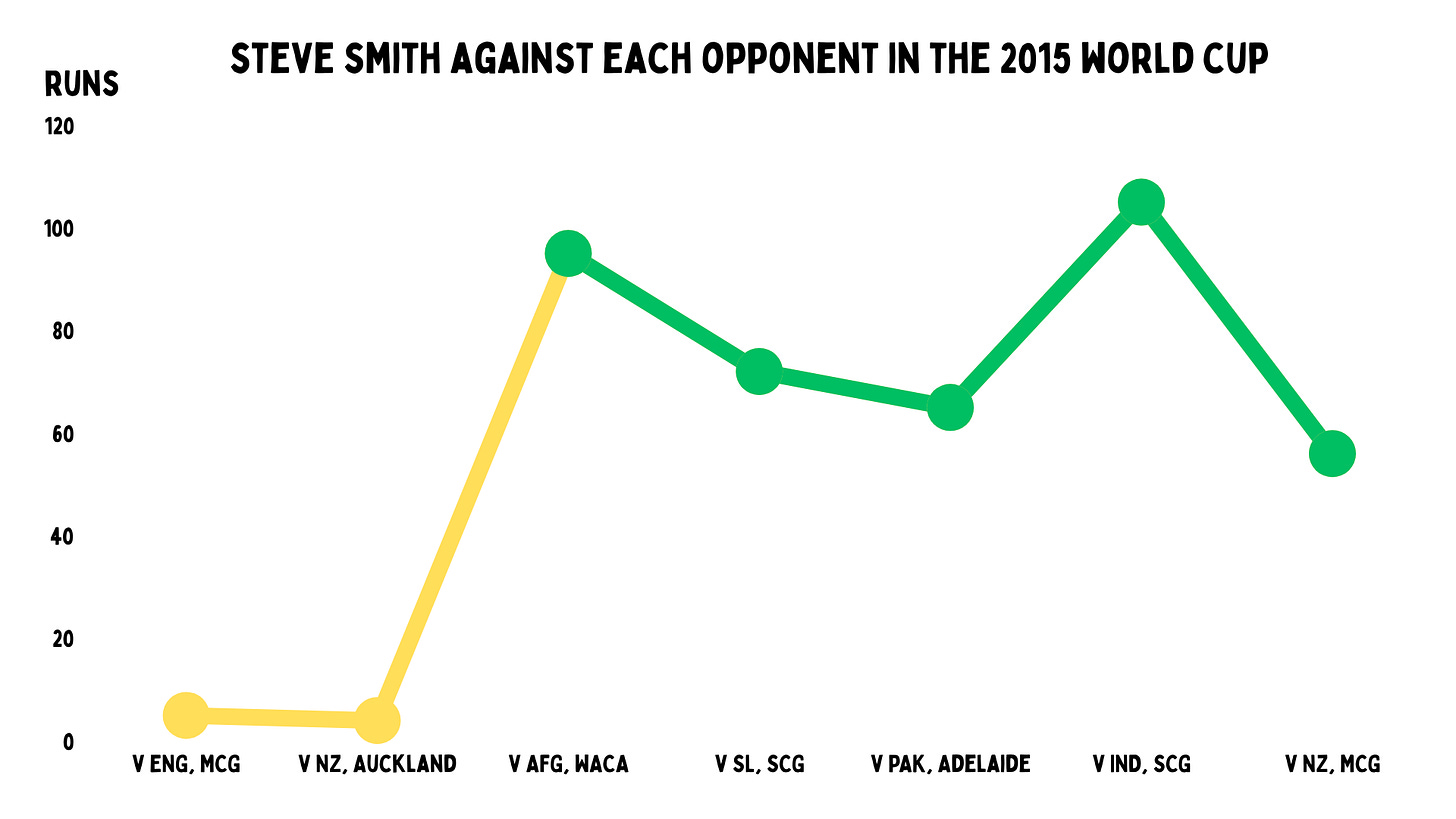

He actually started the tournament with a couple of low scores against England and New Zealand, batting at number four and five respectively. But his entry points (the 8th and the 14th over) were not unusual for a number three. Australia started the tournament with Shane Watson at first drop, but after the famous one wicket loss against New Zealand, Smith would move to the position and score more than 50 five consecutive times, on four different grounds.

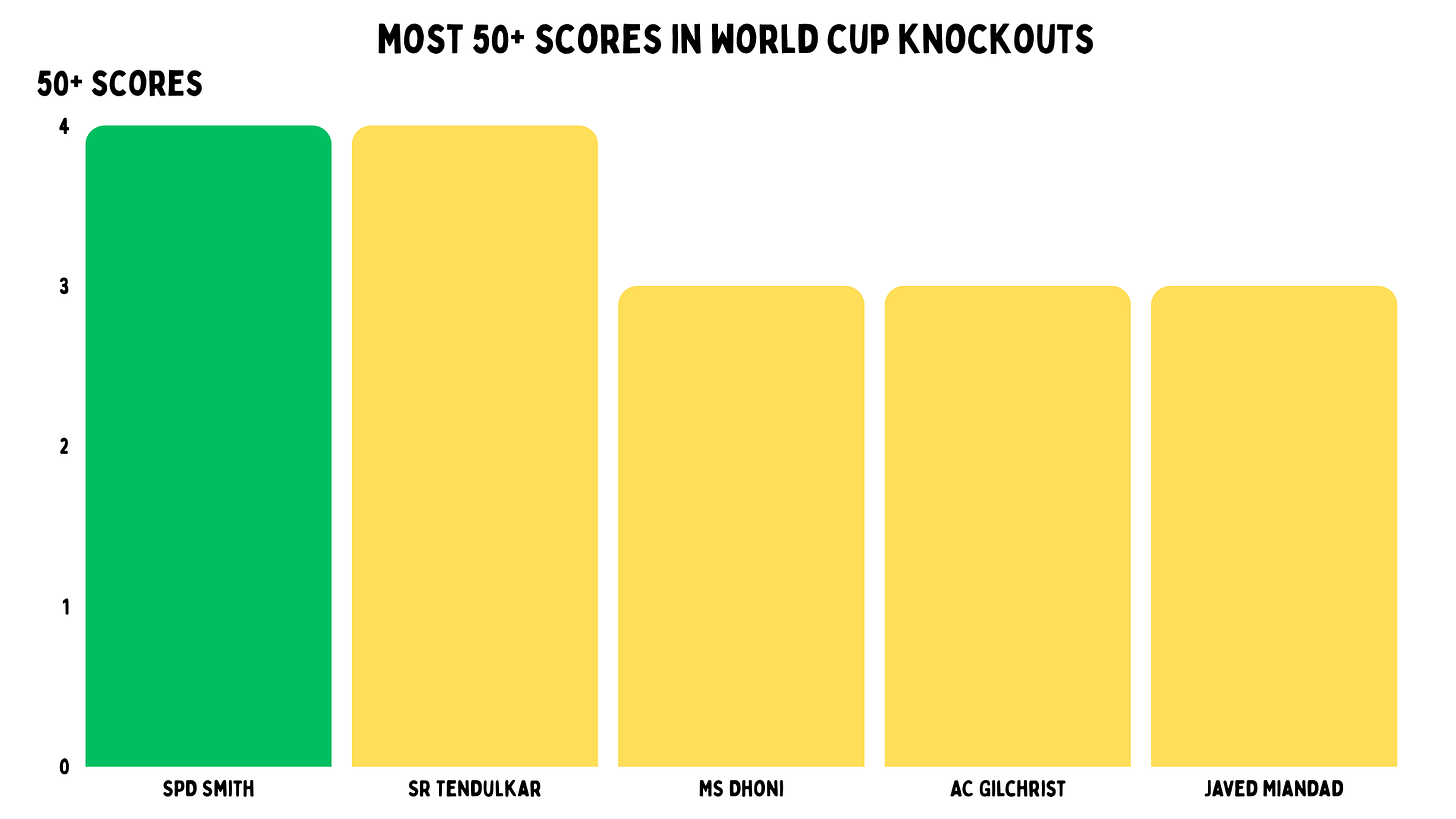

The only other batter to have repeated this feat in a World Cup is Virat Kohli – in 2019 and 2023. What makes Smith’s accomplishments even more special is that three of those fifty-plus scores came in World Cup knockouts. Nobody else who has ever played a quarter-final, semi-final and final in the same tournament has achieved this.

He also has the joint-most fifty-plus scores (4) in World Cup knockouts, alongside Sachin Tendulkar. Smith got his scores in six innings, while Tendulkar has seven. The others on this graph have also played a comparable amount of knocks in these games.

Smith’s fourth score above 50 was against England in the 2019 World Cup semi-final – 85 off 119. Although England chased down the target comfortably, Smith’s knock was still a very good one. Australia were 14 for 3 in the seventh over, and the next-best score in the innings was 46 off 70 by Alex Carey. Only two other batters crossed 20: Glenn Maxwell and Mitchell Starc.

His final ODI innings was another fifty in an ICC knockout game, on brand with his legacy in this format. The only time he made a single digit score in such a game was in the 2023 World Cup final – when he got a wrong LBW decision against Jasprit Bumrah and chose not to review it. In total, he had one century and 12 fifties in 36 innings in the World Cup and Champions Trophy.

When we look at 2019 and 2023 overall, he didn’t really stand out on either true average or strike rate. In fact, both of those values are negative in 2023. He only scored 30 or more five out of ten times. He did play an important innings in the semi-final versus South Africa, scoring 30 off 62 in a tricky run-chase. Like Williamson, he stood out for his ability to score on pitches where others could not. That is when he was at his best.

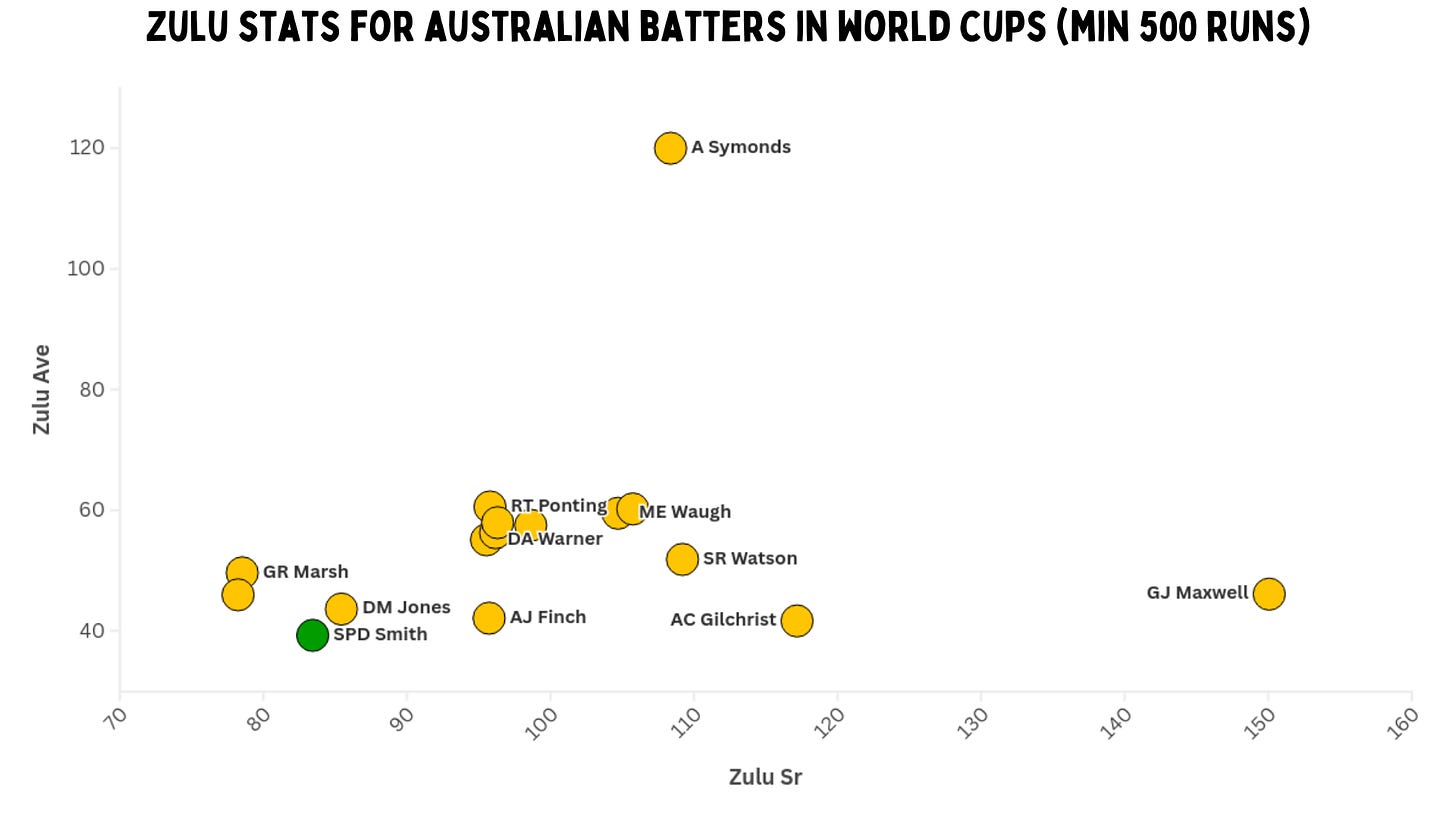

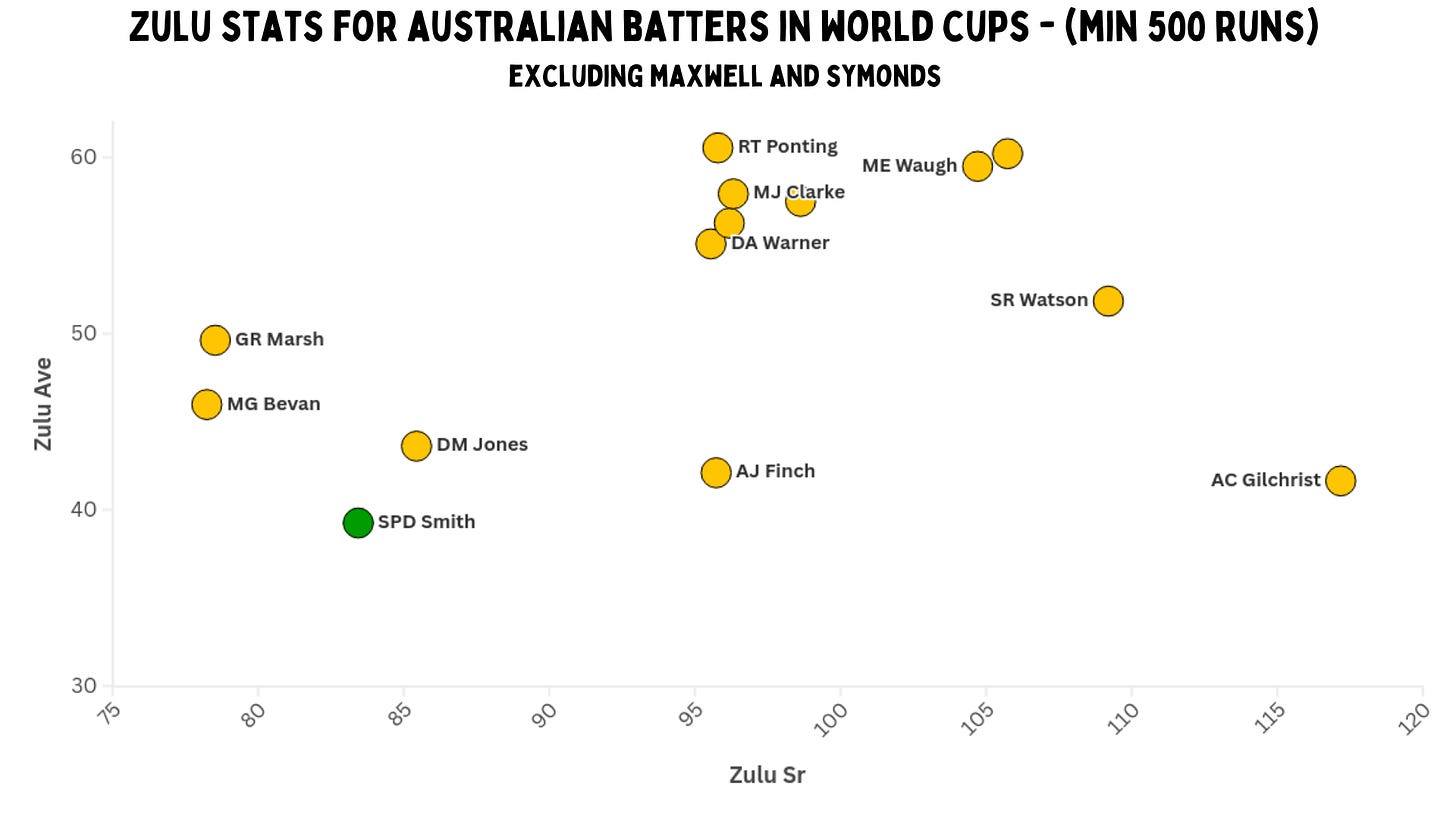

His World Cup numbers don’t scream ‘great’ when compared to the other Australian batters with 500 or more runs. But remember, Australia have more batters with over 500 runs than most, and a few of them were awesome. Also, Smith did play three innings at number seven in his first World Cup in 2011, and batted once at number six in 2019. Those innings do have an impact on his overall numbers in World Cups.

Glenn Maxwell makes the others look silly because of his ridiculous scoring rate, and the same holds true for Andrew Symonds in terms of average.

Here’s the same graph excluding those two. There’s a cluster of batters with a Zulu average between 55 to 60 and Zulu SR in the high-90s. Smith has the lowest average, and only Geoff Marsh and Michael Bevan scored slower than him. Of course, Australia have six World Cup titles to their name for a reason, so the bar is insanely high.

How about adjusted numbers over full careers?

Smith is closest to Damien Martyn in terms of Zulu average and strike rate, and Mark Waugh, Michael Clarke and David Boon aren’t far off either. But it wouldn’t be unfair to say there are quite a few batters with better consistency and speed than him.

So his World Cup legacy is confusing, and he finds it hard to stand out among the Aussies. He was the kind of player everyone wanted even a few years ago. The guy who would make runs when it mattered, albeit a bit slow. But now his entire method seems from another era.

Smith calling it a day from ODIs also means he can focus specifically on Test cricket. He has four tons in his last five Tests. What if there’s another mini-peak coming?

His T20 returns have also risen in recent times, and he seems to be targeting the 2028 Olympics, which does feel like a very Steve Smith thing to do.

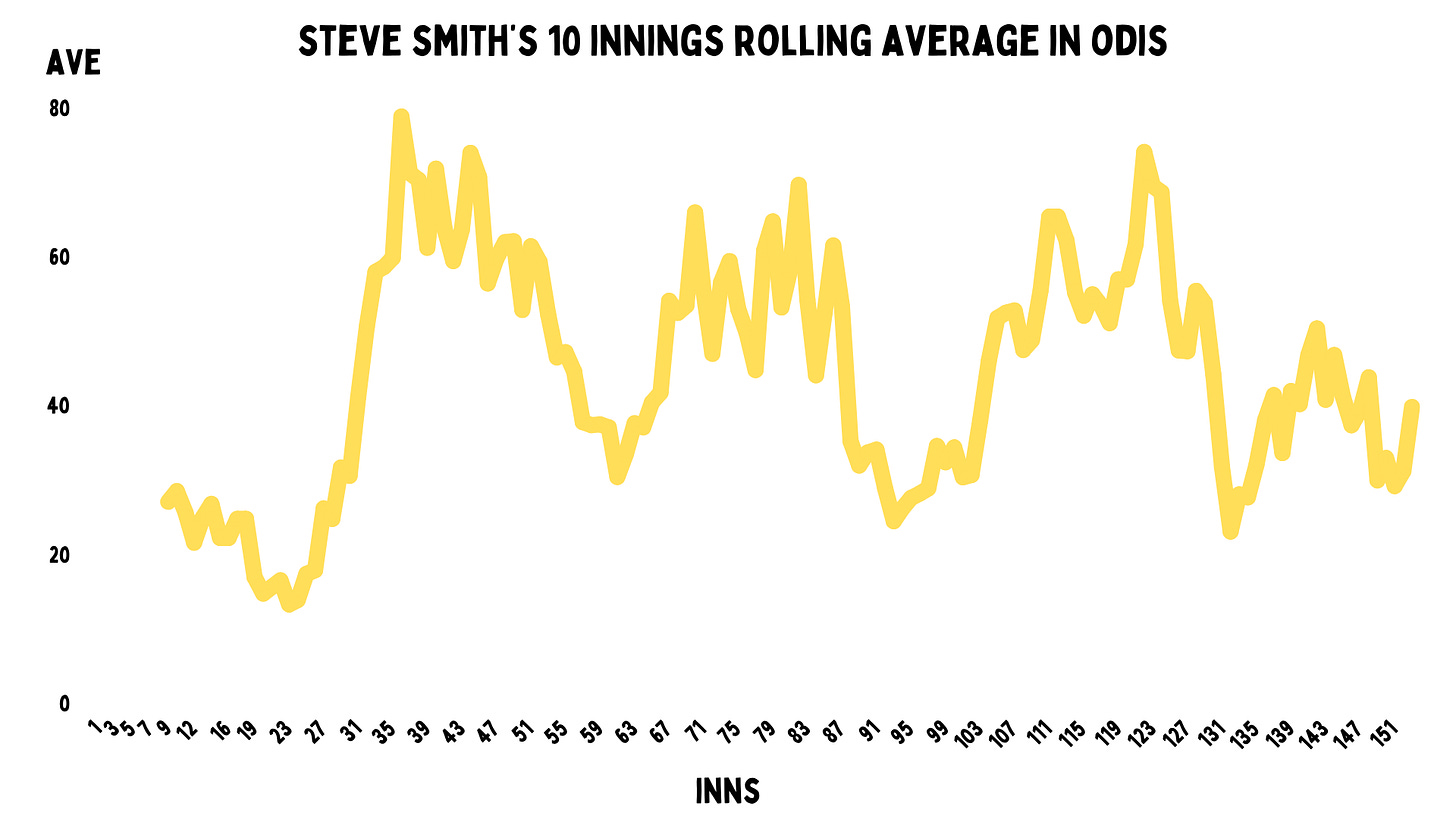

As for ODIs, Smith's 10 innings rolling average suggests that his success in the format is nowhere near his peak years. Even though true values suggest his numbers in 2025 are close to those in 2020, it’s from a sample size of five innings this year compared to ten in 2020. Plus, he wasn’t great in 2023 and 2024.

His powers have withered in 50-overs cricket, and he'll be past his 38th birthday when the 2027 ODI World Cup kicks off.

Watching him play it at times, I did feel strong he’s just-not-that-into-you vibes.

It makes sense for Australia to identify their next number three or four in ODIs for the next two and a half years. So looking at things long term for Australia, Steve Smith might have timed his ODI retirement as well as his awkward nudges on the onside.

No matter how you view his entire career, he’s definitely played a role in Australia winning white-ball cricket’s most coveted title, twice.

He wasn't the next Ricky Ponting, but he's been better than your normal average Marsh. He loved batting at three, versus India, at home and in World Cup knockouts – all of which culminated in his most memorable innings in the format. As far as careers go, those are nice boxes to tick. So if you saw those knocks, you’ll rate him very high. But overall, Smith just never took apart 50 overs like he can the red ball.

Not an all-time great, rather an all-time good in ODI cricket.