Who is the greatest ODI batter of all time?

It also comes down to what kind of ODI players you like best.

The first one-day international was a 40 over match with eight balls per over. It was played at the Melbourne Cricket Ground between Australia and England in whites, with a red ball. Australia won by five wickets and 42 balls to spare. Offspinner Ashley Mallett thought the game was ‘a bit of a joke’. It really wasn’t until the 1990s that everyone really started taking it seriously.

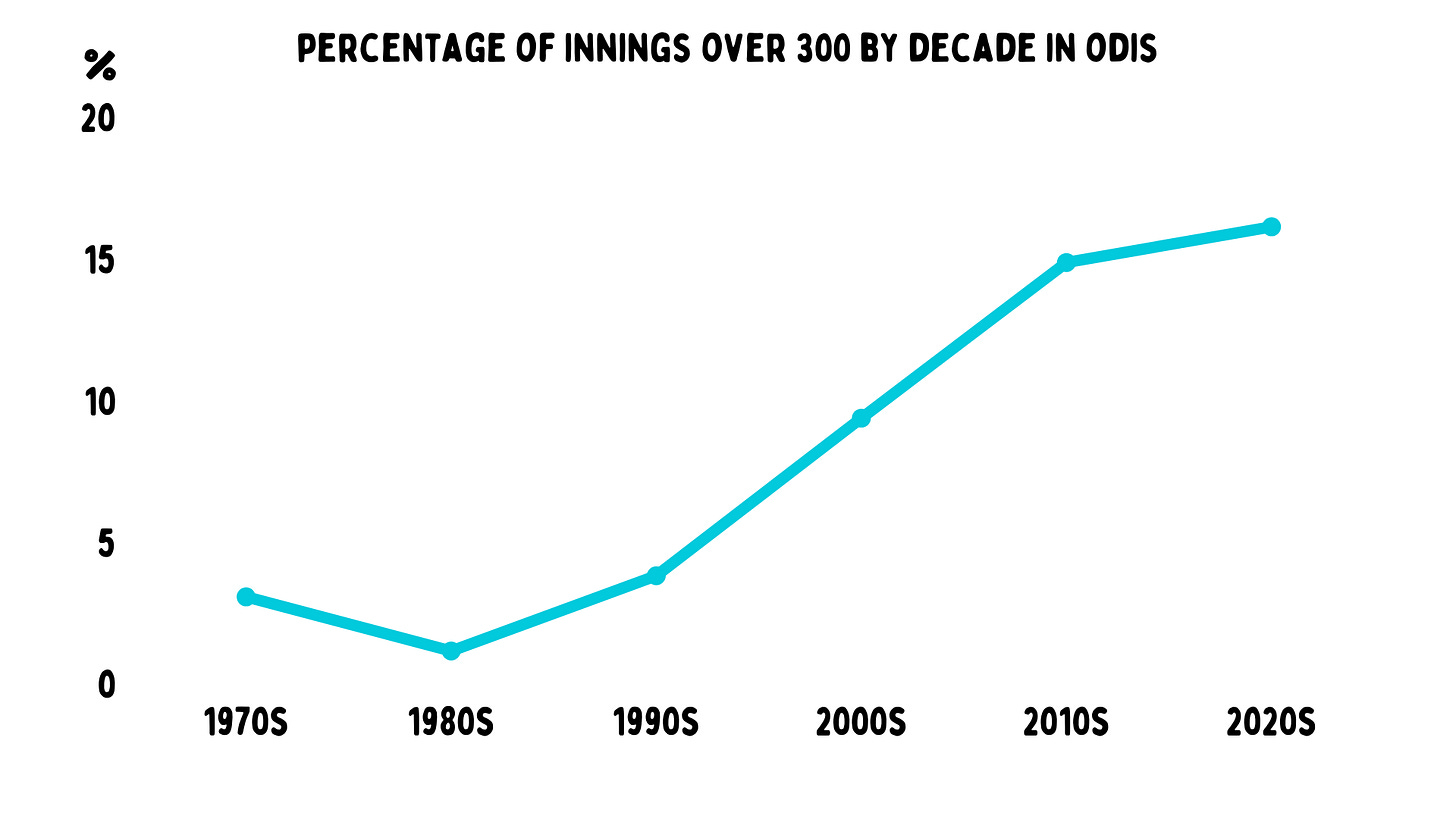

Since then, ODI cricket has changed massively. Teams are scoring over 300 runs like it’s a trip to Cleveland in the modern game. The evolution of the ODI game is down to multiple factors such as changes in the number of overs, field restriction rules, the colour and number of balls used in a match and larger bats, along with a higher emphasis on power-hitting – largely due to T20 cricket.

Apart from geeking and passionately arguing for your favourite players, why does it matter who the greatest of all time, or the GOAT is? Well, we simply can’t look at the stats of players of the previous generations with a modern-day lens. For instance, Viv Richards’ numbers in his era were similar to Rohit Sharma’s before the 2023 World Cup. Run-flation is real.

So, who is the greatest ODI batter of all time?

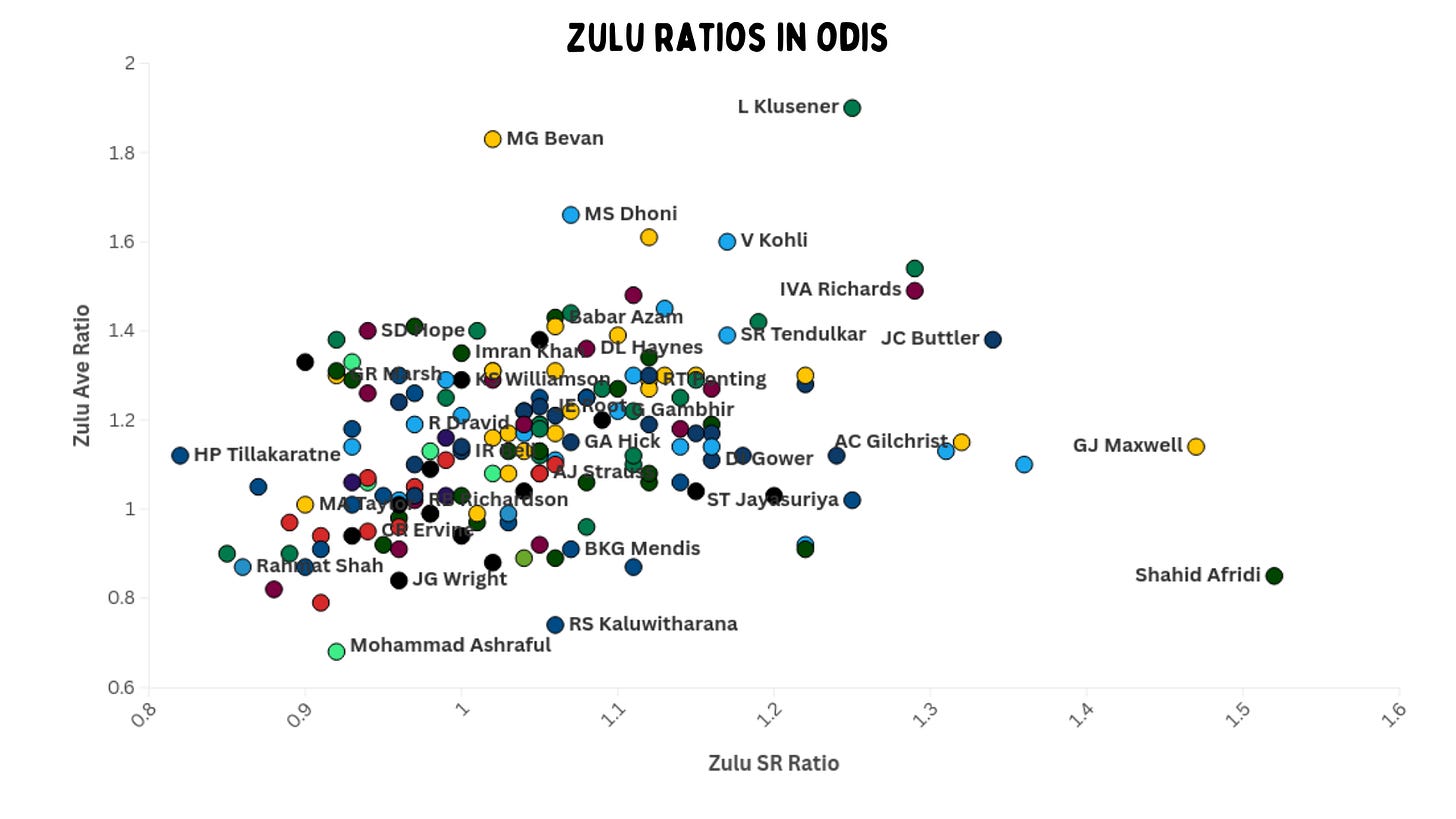

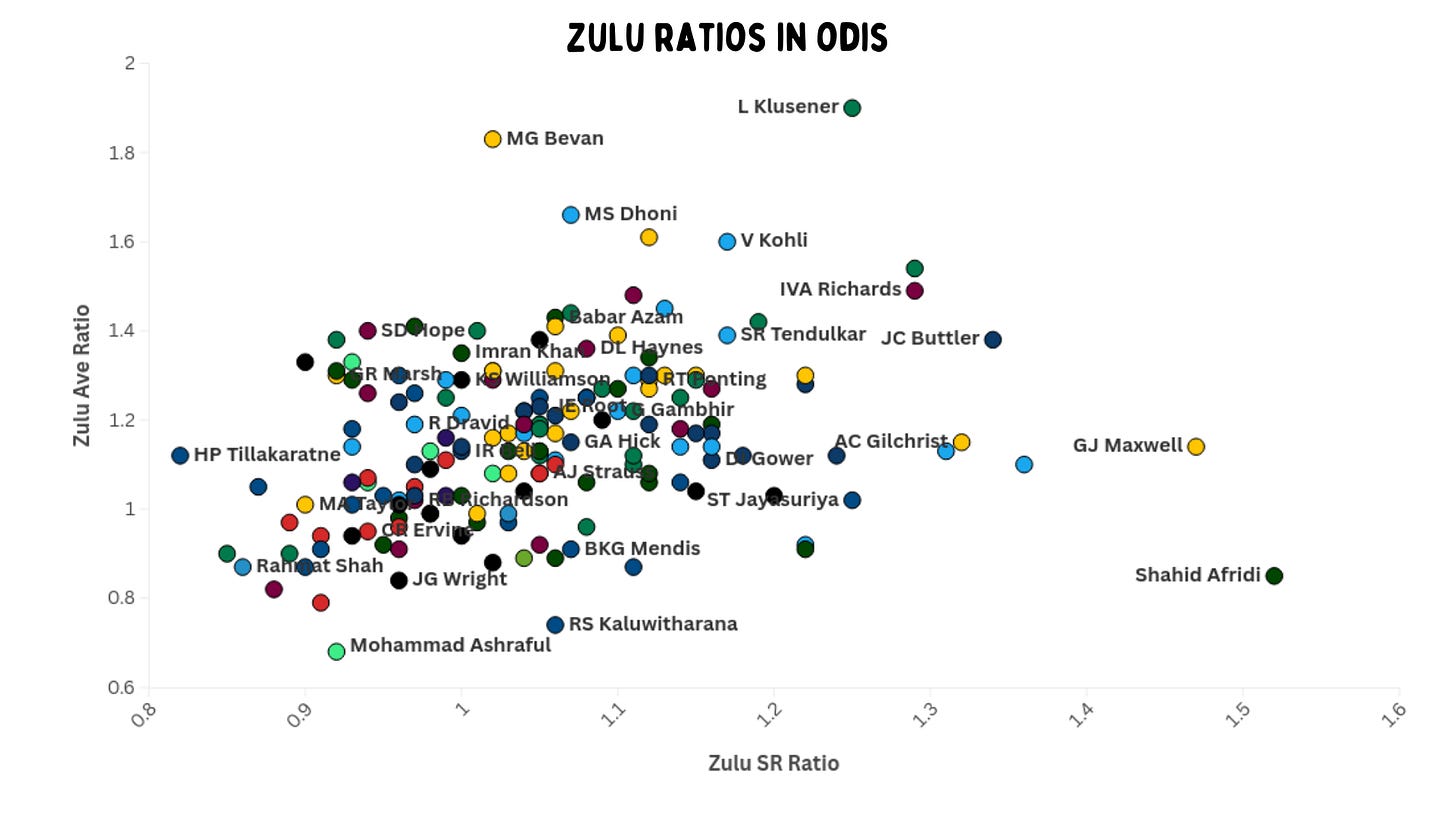

The Zulu ratios are quite simple. We see how good a batter is in his batting position for their eras and normalise them to the modern era. If a batter has batted in numerous positions, each position is weighted by the number of times they have batted at that position. We’ve defined the modern era as 2016 to now.

The assumption for these statistics is linearity. Essentially, we assume that if a batter was 20% better than expected in the 1980s, they're projected to be 20% better now. That may or may not be accurate; they could be 10% or 30% better depending on what suits their gameplay. But for the sake of simplicity, we'll stick with that premise.

You may be wondering why we’ve called this the Zulu metric. Take a look at this graph and see where Lance Klusener, also known as Zulu, is. He’s 1.9 times better on average and 1.25 times on strike rate. He was truly his own genre. He was a batting allrounder who was treated like a bowler who can bat by South Africa for most of his career.

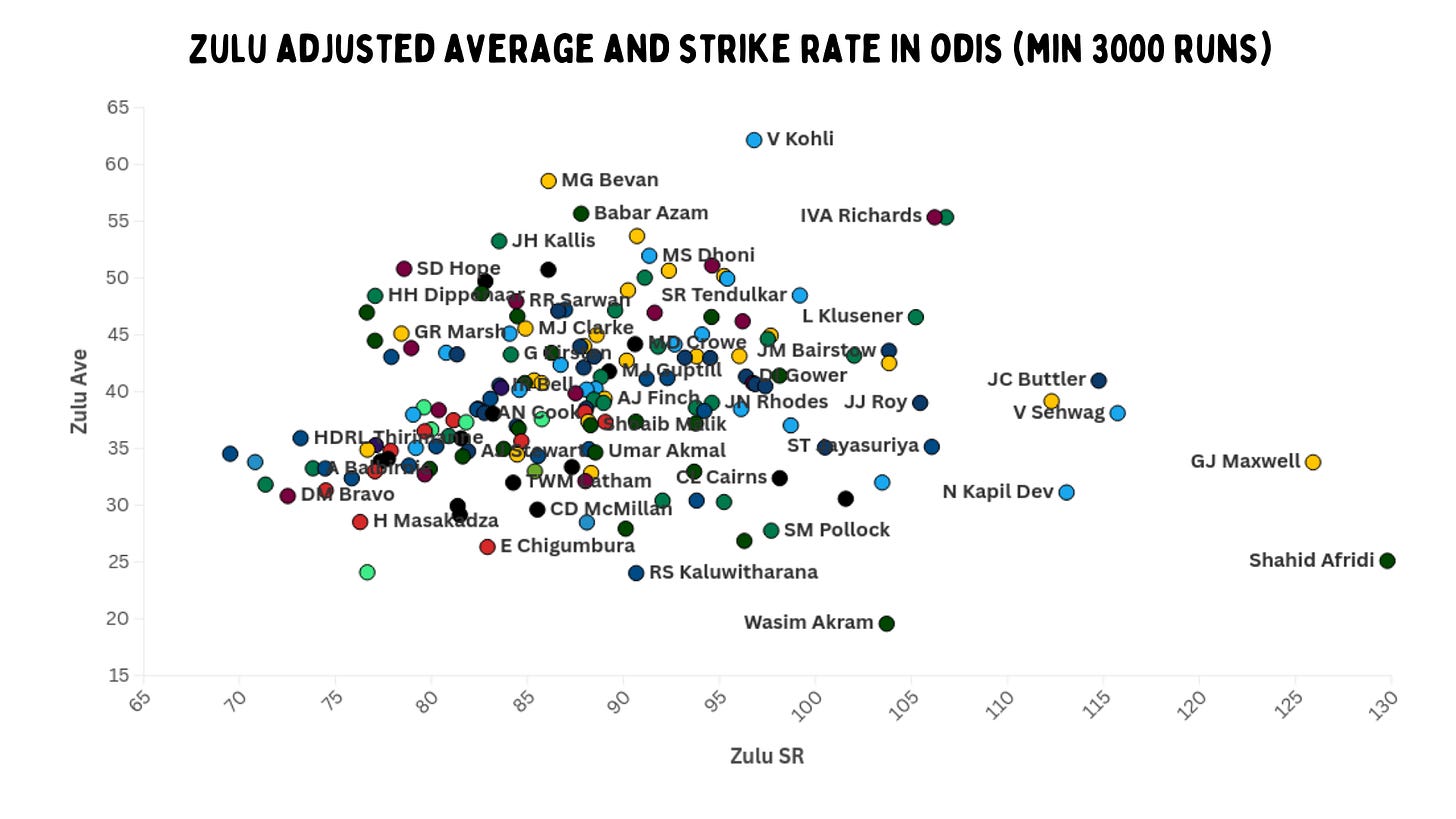

Now let’s actually display these ratios in a more familiar format – the Zulu-adjusted average and strike rate.

Virat Kohli has the highest average – he is the only one to cross the 60 mark. Michael Bevan is second, with 57.4. AB de Villiers and Viv Richards average about five runs less than Kohli, but they are nearly 10 runs ahead on strike rate. Klusener scores at almost the same rate as them, but averages about ten runs less. Sachin Tendulkar is another batter who performs incredibly well on both metrics, despite playing over 450 matches in the format.

Rohit Sharma, Gordon Greenidge and Michael Hussey average close to 50 at a strike of 95 on this metric. Dean Jones, Ricky Ponting, Hashim Amla and MS Dhoni are close neighbours, averaging over 50 at a strike rate of over 90. These are some of the greatest batters, who are incredibly important in the evolution of the format as we know it. Matthew Hayden isn’t too far off them either. Another batter with an incredibly high average is Babar Azam, who is going through a significant form slump right now.

Shahid Afridi is a massive outlier in terms of strike rate. Essentially, his adjusted strike rate is like that of an anchor in T20s. Maxwell is a bit slower, but a lot more consistent than Afridi. We see Virender Sehwag, Jos Buttler and Adam Gilchrist in a cluster – though the English skipper bats in the middle order. But let’s talk briefly about the Indian opener.

We believe Sehwag is the most underrated ODI batter ever. To this day, it confuses me that a vast number of fans question his ODI record. He played in the powerplay the way it was supposed to be – obliterating bowlers and changing the plans of the opposition. Few openers have utilised the first ten overs better than him.

Kapil Dev is another batter that strikes at over 110, and averages over 30. Sanath Jayasuriya and Jason Roy have a similar strike rate of around 105-106. Although Roy is a bit ahead on average, Jayasuriya played nearly thrice the amount of games as him.

From these numbers, we realise that as a cricket community we have somehow underrated an entire era of ODI openers – the ones who played in the 1970s and 80s. Desmond Haynes, Greenidge’s opening partner, was a solid anchor-type batter. Kris Srikkanth was basically playing his own version of Bazball, but because he didn’t have a huge average he isn’t remembered the same way.

The other extreme of this is Sunil Gavaskar being considered a worse ODI batter than he actually was – his projected stats in the modern era would have been the same as Navjot Sidhu, who is thought of as a much more attacking player because of his six-hitting.

Who are the best batters by each match innings?

Shubman Gill has basically started his career as the best first-innings batter ever on the Zulu metric. Of course, it’s a small sample size, but it has been a ridiculous start. But the real boss of the first innings is Viv Richards. De Villiers is close in terms of strike rate, but Richards is averaging a staggering 10 more.

Zaheer Abbas and Dean Jones also have a brilliant record. Both those batters have been lost in ODI history, but both of them played a great part in the evolution of the format. Jones especially inspired great Australian ODI batters like Ricky Ponting. It’s fascinating that we see Hussey, Ponting, Dhoni, Tendulkar, Kohli and Haynes with very similar numbers in the first innings. Hashim Amla and Rassie van der Dussen are close to them as well. Babar is slower, but only four batters average more than him.

Enough about averages, I feel the need for speed. Again, Afridi and Maxwell top the charts on strike rate, but Maxwell averages nearly eight runs more. Kapil Dev has the fifth-best scoring rate of the batters on this graph. Sehwag and Buttler average above 40, and strike at a little less than 120.

In chases, Virat Kohli’s numbers are just insanity. His Zulu metrics are an average of 70 and a strike rate of 97. De Villiers scores at a run a ball, and still has the third-highest batting average. Richards has a record that pales in comparison to his first innings numbers, but it is still incredible – averaging 52 at nearly a run a ball.

Bevan, one of the greatest chasers ever, is second on Zulu average. Another player of a similar archetype – taking it deep in a chase – is Dhoni. But their adjusted numbers aren’t as similar as we would have expected. Bevan averaged more, but Dhoni was quicker.

Again, Afridi is the quickest, striking at nearly eight runs per over. Maxwell, Gilchrist, Sehwag, Klusener and Roy are the others in the top five. Bairstow isn’t far off the last three either, and he does it while averaging nearly 50. The fact that we see so many players from that great English white-ball side shows they were incredible in run-chases. After the end of the 2015 World Cup till the 2019 World Cup final, they had the best win-loss ratio (3.09) of all teams batting second.

Apart from the more obvious ones, the other great batters in chases are Shane Watson and Hansie Cronje. Interestingly, Gavaskar’s numbers – despite the famously slow World Cup innings against England – also hold up batting second. It’s not too far off Ponting and Dhoni's records on this graph.

True values look at how much better or worse than the mean a batter performs for the balls they face. This accounts for the phases they bat in as well as the pitches. We’ll use this to look at who are the best batters in each phase, and against pace and spin.

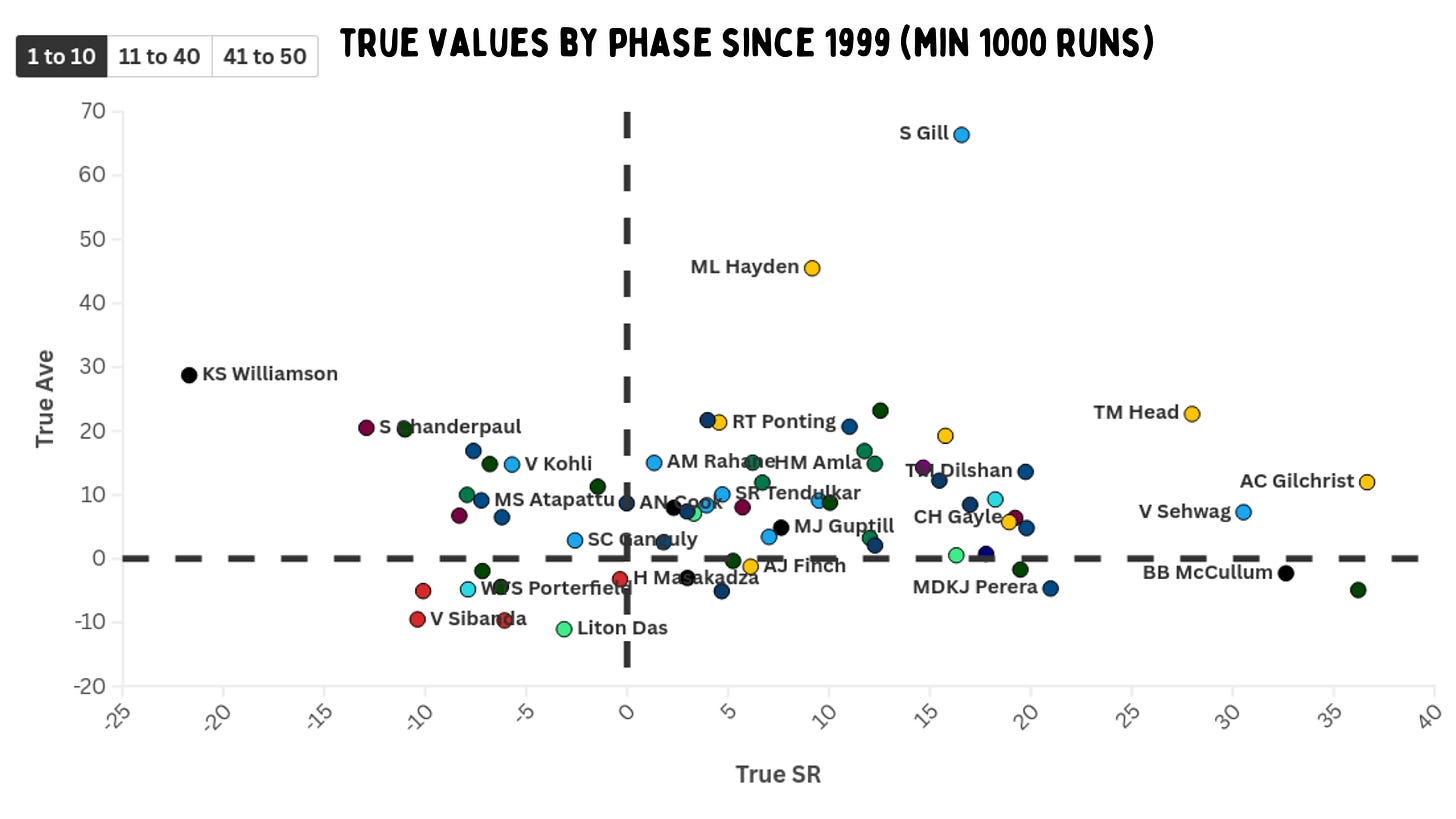

Gilchrist is the quickest scoring batter in the powerplay, striking at 37 more than expected with a true average of above 10. Afridi isn’t far behind on true strike rate, but he has a negative true average. McCullum, Sehwag and Head complete the set of the five quickest scorers in this phase. Gill has an outstandingly high average, but it’s from a small sample size compared to some of the others. Hayden – Gilchrist’s opening partner – had a true average of more than 45 while still striking at nearly 10 more than the expected rate.

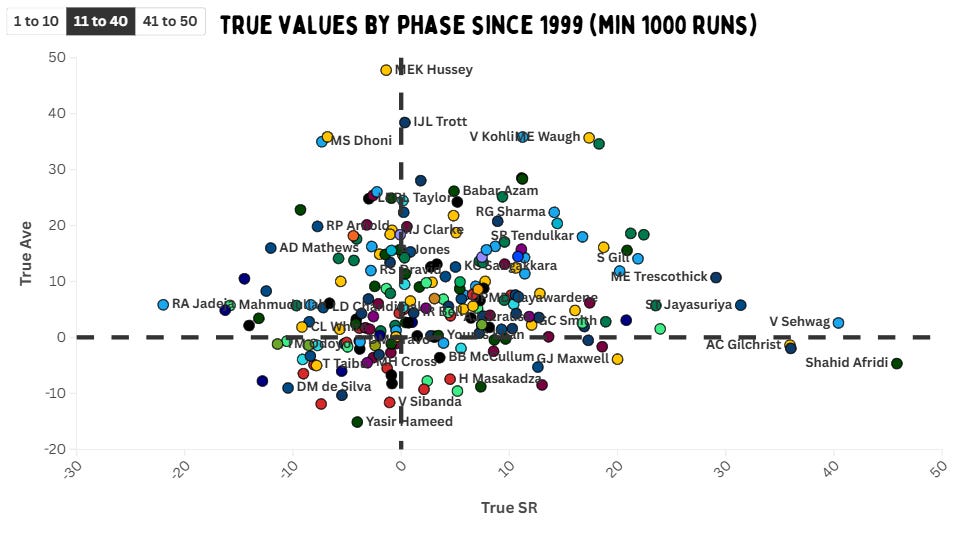

Five openers continue smacking the ball around even after the field restrictions are lifted – Afridi, Sehwag, Roy, Gilchrist and Jayasuriya. Hussey has the best true average from overs 11 to 40, but at a negative true strike rate. Kohli does his best work in this phase of the game – with true averages comparable to Dhoni, Bevan and Trott – but at a true strike rate well above 10. De Villiers and Mark Waugh have a similar true average at a true strike rate of around 17 to 18. However, for Bevan and Waugh, this doesn’t include their career numbers before 1999.

De Villiers is an outlier in the death overs as well, with a better true strike rate than the likes of Maxwell and Afridi. Buttler is a bit slower, but has the second best true average. Rohit and Morgan are the other two batters that have a true strike rate of over 40 in the final ten overs of the innings. Miller has the best true average.

I’ve said this before, AB de Villiers might just be one of the greatest players ever against true fast bowling. But this includes all types of pace – medium, medium fast and fast – and he’s still the most obvious outlier on our metrics. Gill has started his career with de Villiers-level numbers against pace, but he has some time before getting into the territory of greatness. Bevan, Trott and Kohli make the top five in terms of true average. Afridi, Gilchrist, Sehwag, Jayasuriya and Maxwell all have a true strike rate above 25.

Afridi is again the quickest against spin – except this time nobody even comes close. Maxwell is also an outlier, yet his true strike rate is a staggering 25 less than Afridi’s. Tendulkar, Brian Lara and Buttler are the others in the top five – and they also have solid true averages. De Villiers is just a bit behind Tendulkar. Inzamam-ul-Haq, Sourav Ganguly and Gautam Gambhir are also really good against spin bowling.

Dhoni and Hussey have very similar numbers against spin – massive true averages at true strike rates close to par. Interestingly, they both also played together for CSK – a franchise that built their dominance on a spin-friendly home wicket. Marvan Atapattu is third on this metric. Despite Kohli’s current issues against spin, he has a superb record against it – a true average above 35 and a true strike rate of over 10. Rohit is ahead of him on true strike rate, but at a slightly lower true average.

Graeme Smith, what’s the deal here?

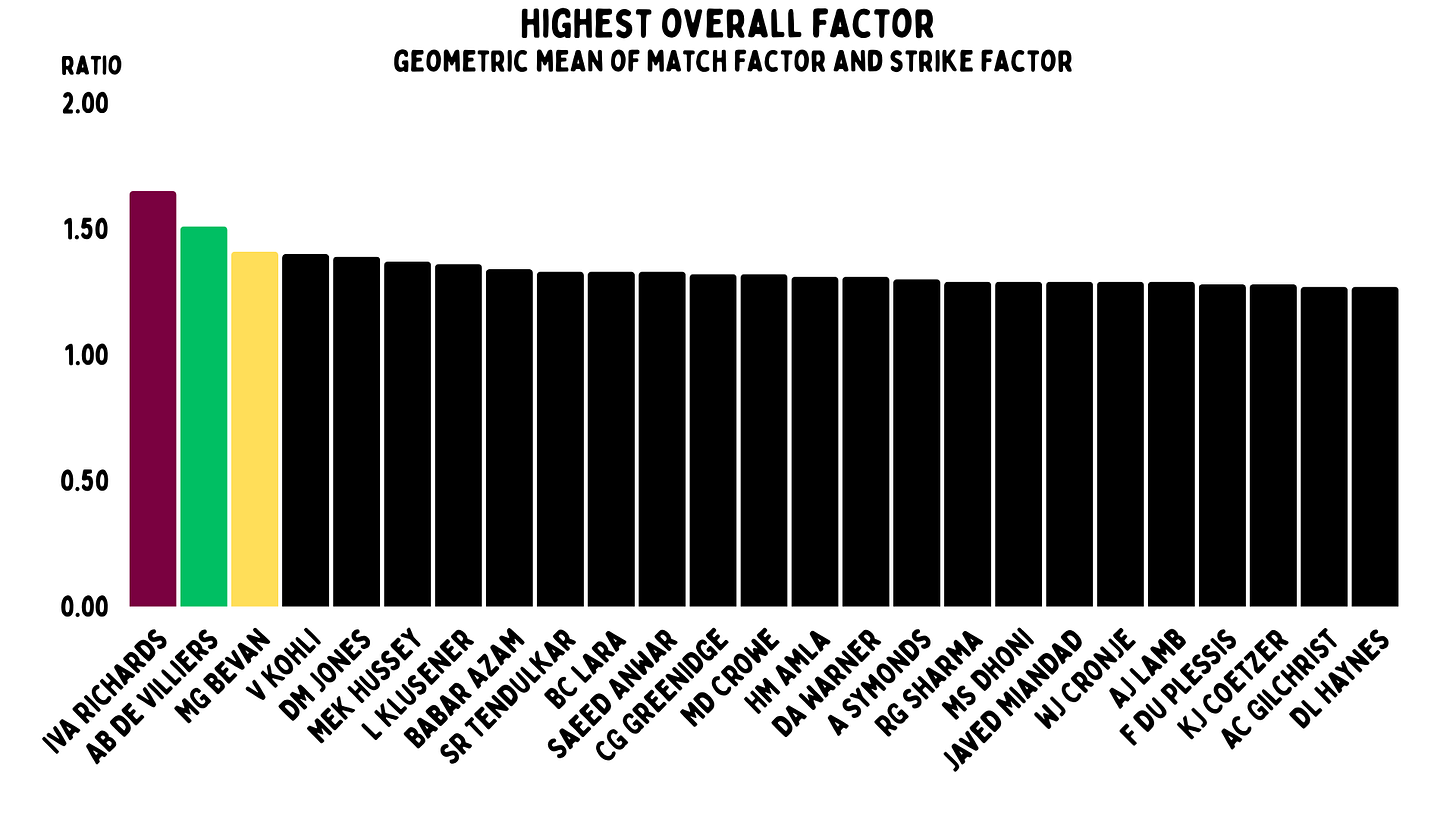

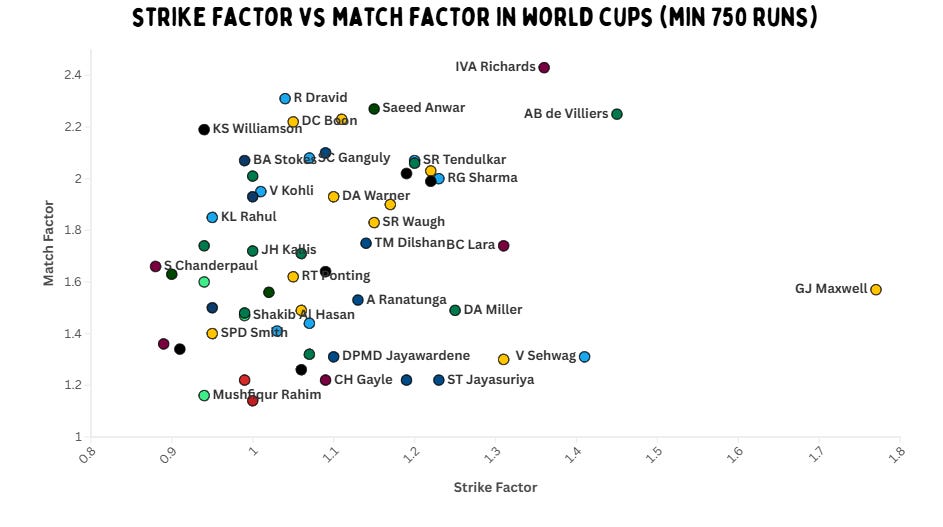

Here’s a quick recap on match factor – it is the ratio of the batter’s average compared to the others in the matches they have played. Strike factor is the ratio of the batter’s strike rate compared to the rest. The only difference from what we do for Tests is that we don’t look at just the top six batters. So all batters that have batted in those matches are considered.

This graph rewards players who don’t play on strong teams, and makes it difficult for the ones who do so – unless you’re an outlier in a great side like Richards or de Villiers.

In terms of strike factor, we again see familiar names – Afridi, Kapil, Maxwell, Richards and Sehwag. But Richards also has the third-best match factor, only behind Bevan and Hope – two batters who score slower than their teams.Sean Williams, Sikandar Raza, Brendan Taylor and Paul Stirling are four players who star on this graph. Martin Crowe, Lara, Tendulkar, Allan Lamb and Arjuna Ranatunga are also incredible compared to their teams.

When the rest of the players in a match score at less than five runs per over, Bevan shines the brightest in terms of match factor, while being 4% up on strike rate. He averages 119% more than the others. Hussey’s second, with 112%. Kohli is quicker than them and is 96% ahead of the others in terms of runs per dismissal. Misbah-ul-Haq, Greenidge, Dhoni, Chanderpaul, Yousuf and Kallis all have a par strike rate but are more than 75% up in terms of average. De Villers, Andrew Symonds and Rohit also perform really well on both metrics.

But all things considered, nobody is close to Richards. Only Kapil and Afridi score quicker, and only Bevan, Hussey and Kohli have a better match factor. He has a better strike factor than even the likes of Sehwag and Gilchrist. Most batters usually have to compromise on at least one metric – but that doesn’t seem to hold up for Richards.

It is worth noting that Richards has actually played a high percentage of such games in his career compared to many others. Naturally, modern-era batters have a lesser proportion of such innings.

In matches where none of their other teammates have made a half-century, Kohli is by far the best in terms of match factor. Hussey, de Villiers and Neil Johnson are not too far behind. But neither of them haven’t been in this situation very often. Tendulkar has played the second-most such innings (118) after Jayasuriya and has the most runs – nearly 5000 of them – with a match factor of 2.85 and a strike factor of 1.34. Afridi, Kapil and Sehwag are the outliers on strike factor.

We compute the overall ratio by taking the geometric mean of match factor and strike factor. The geometric mean is the square root of match factor multiplied by strike factor. To make this clear, this is not like the ‘BASRA’ metric which adds two different units. The match factor and strike factor have different scales and taking an arithmetic mean would not accurately represent the story we want to tell.

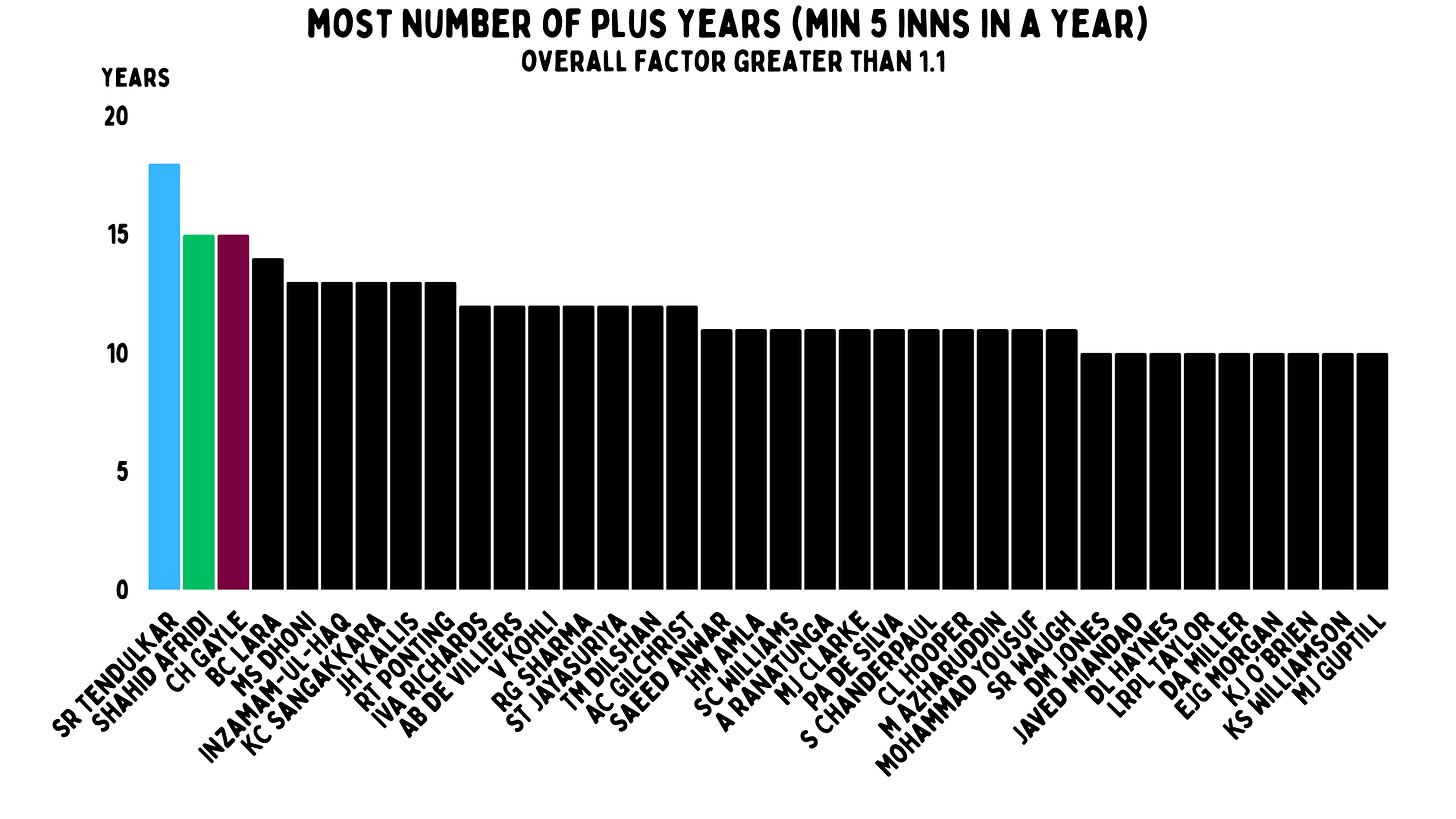

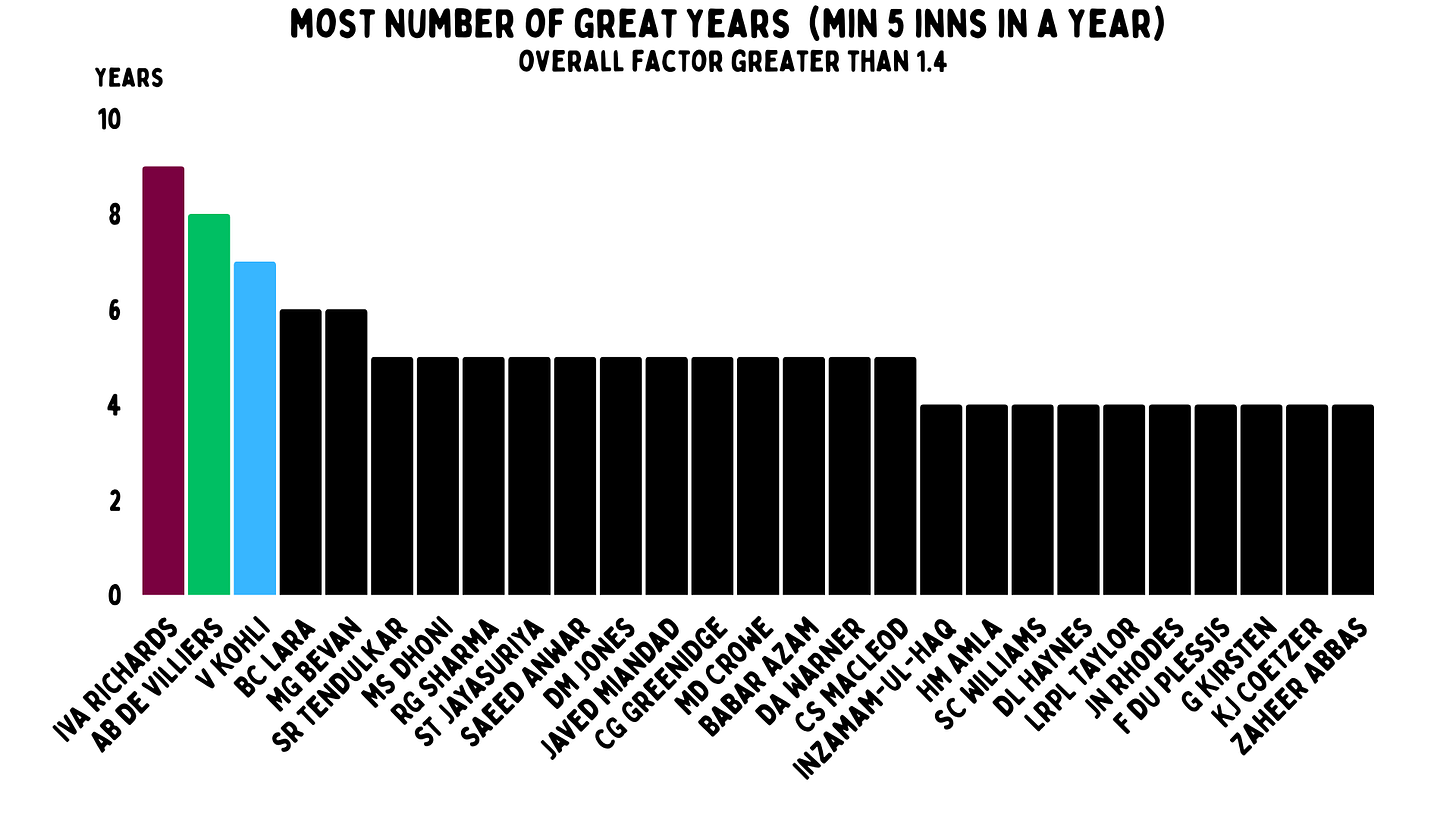

When we talk about greatness, it is important to look at how many plus years and great years a batter has had. This helps us determine the longevity of a player. For those many years, their team doesn’t have to worry about finding another great or above-average player. So, how do we define such years?

A plus year is when the overall factor is greater than 1.1. In the case of a great year, that mark is 1.4. The batters with the most plus years is Tendulkar, with 18. Afridi and Gayle are joint-second with 15.

For great years, the top three are Richards, de Villiers and Kohli – they have nine, eight and seven years of being great. Lara and Bevan are at six, while many others are tied at five.

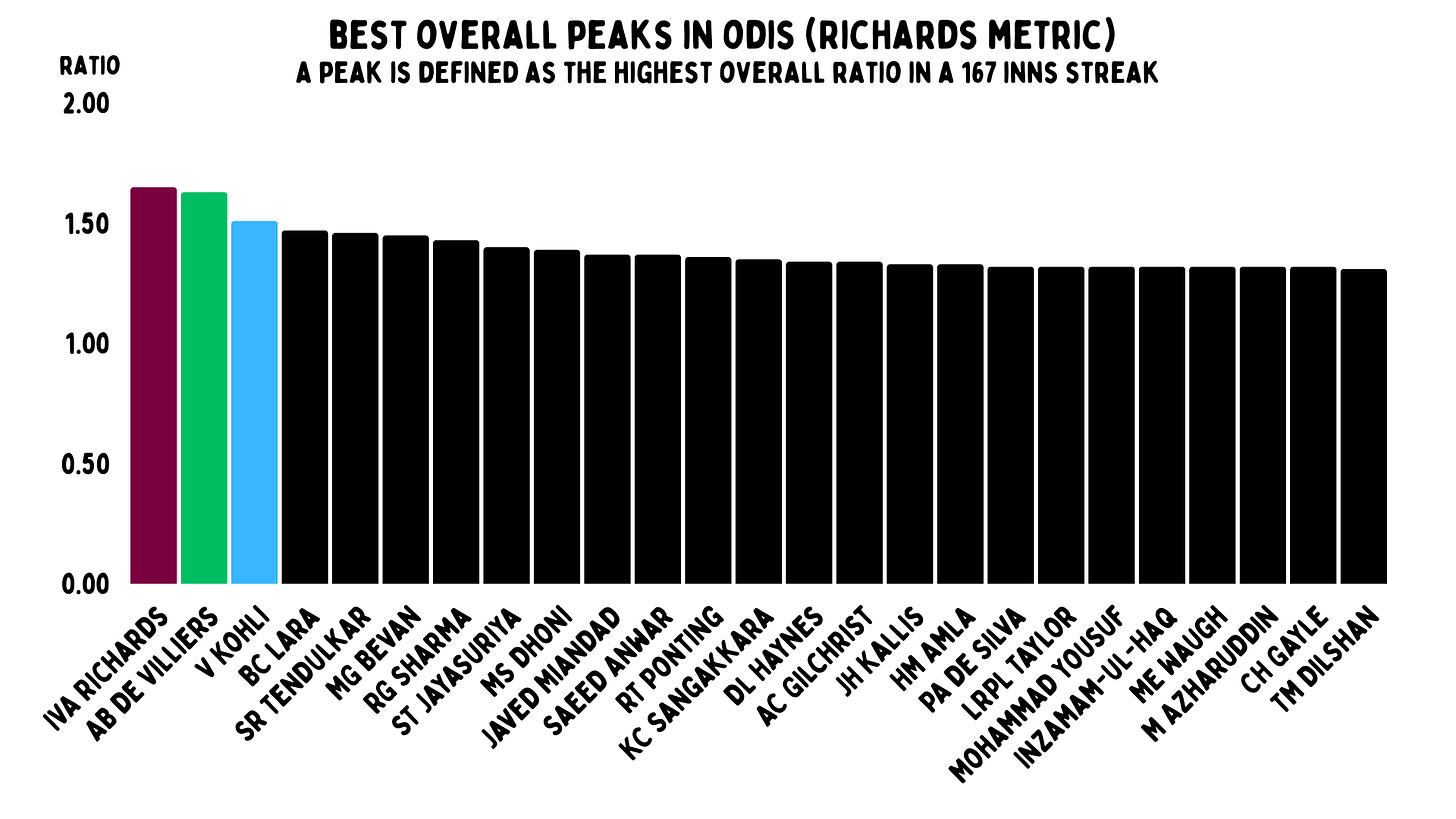

Unlike Test cricket, defining a peak in ODIs is quite tricky. We aren’t just dealing with averages, we also have to worry about strike rates. So we’re going to be looking at batters that were the best on both metrics. Along with that, we’ll combine the two metrics to get an overall ratio to determine which batter managed a great balance of strike rate and average over a significant period.

We’ve decided to use 167 innings as the threshold. Why 167? That’s the number of innings Richards had batted in. And a bit like Bradman, you can make an argument that his entire career was one long peak. He had 12 plus years, with nine of them being great.

And you can just see why we named this after Viv Richards. His overall ratio was 1.65. That is absolutely ridiculous over such a long period of time. You might have noticed a certain freak called AB de Villiers right behind him – he has an overall ratio of 1.63. He loses to Richards by the barest of margins.

There’s a bit of distance between these two and the next best, Virat Kohli, who still manages a great overall score of 1.51. After him, we also see Lara and Sachin. Lara was an underrated ODI player. He also played for a weaker team than Sachin, and featured in lower-scoring games.

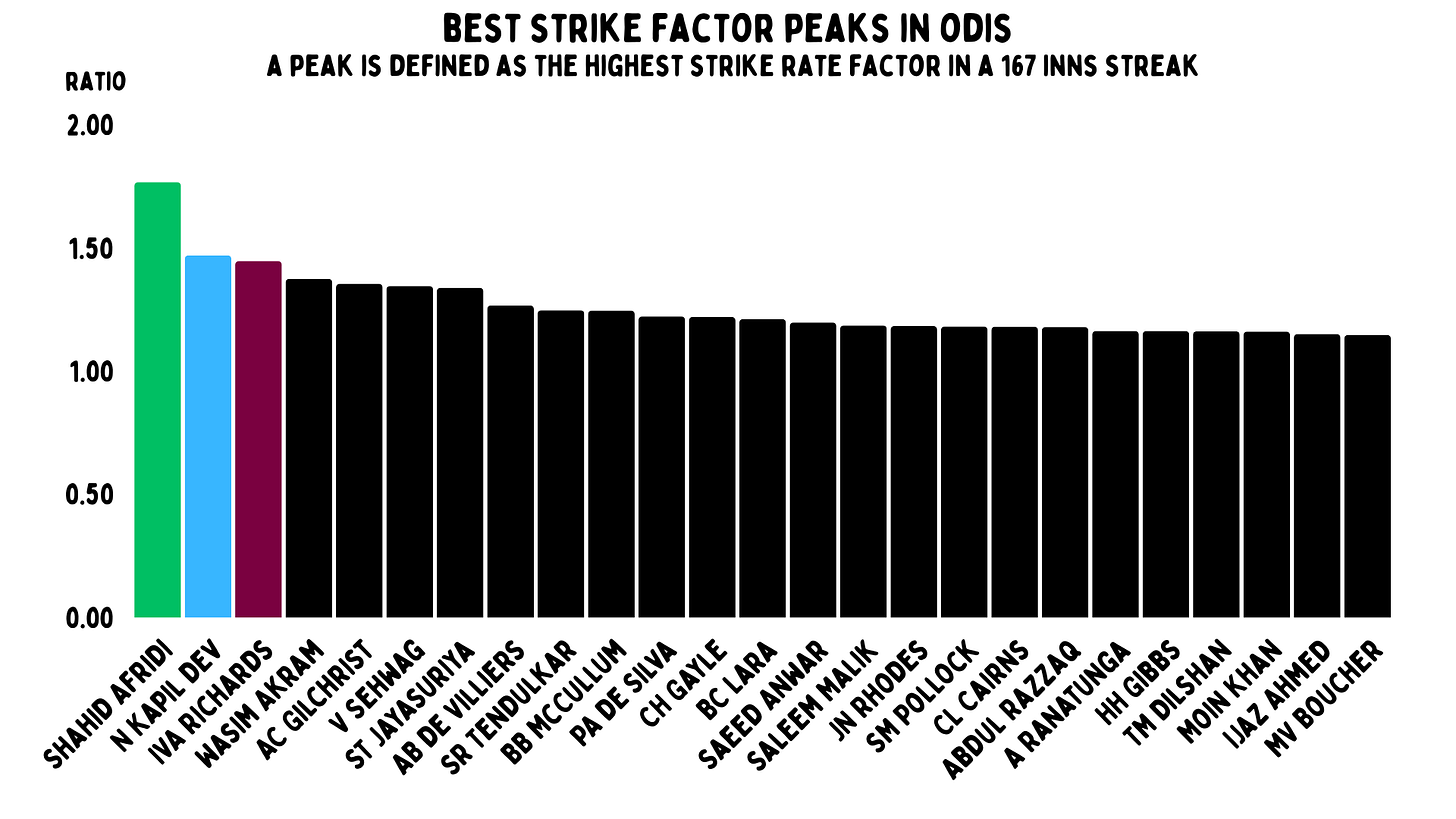

We also decided to see which batters had the best strike factor over a 167 innings stretch. Look at our man Afridi here. He had a strike factor of 1.77. 1.77! He was 77% faster than the other batters in the same games. People just did not understand what Afridi was doing at his best, often calling him inconsistent. We may need to call this the Boom Boom variant of the Richards metric. A distant second is Kapil, with a strike factor of 1.47. Just behind him is Richards, only a miserly 45% faster than the rest. Clearly, they were not inspired enough by Ben Duckett.

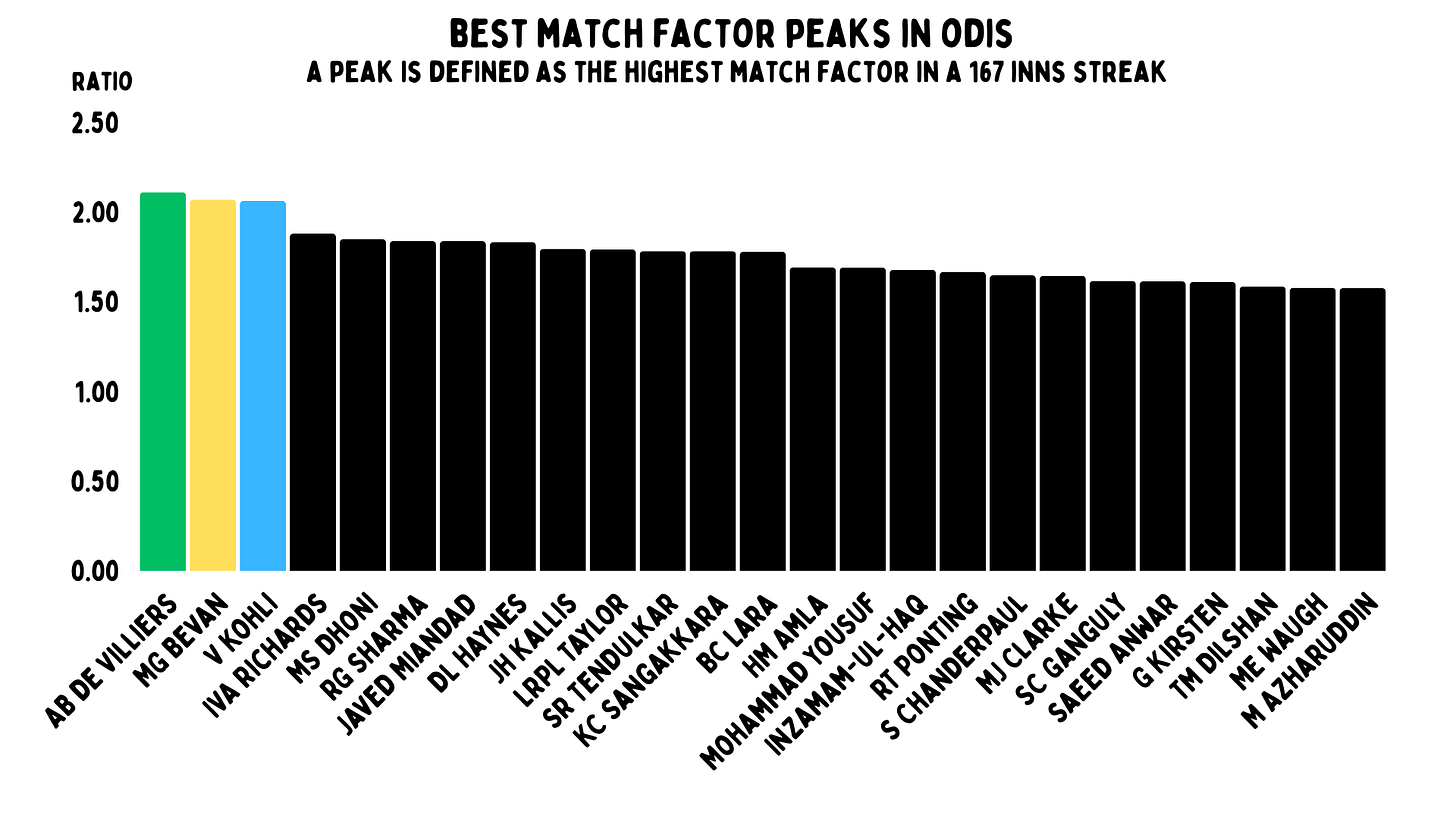

There’s a clear top tier here. AB de Villiers, Michael Bevan and Virat Kohli are the only batters with a match factor of over two. De Villiers tops this with a match factor of 2.11. He was 111 % better than the others in his games. At his best, there were few better than him. Just behind him are Bevan and Kohli, two batters who performed vastly different roles, but are widely regarded as the greatest chasers in ODI history. Bevan was the first finisher who basically batted like an anchor, while Kohli is one of the most efficient run-scorers ever in the format.

Doing well on the biggest stage definitely helps in terms of legacy, and we also think it should reward batters when we are talking about greatness. Maxwell is 77% quicker than the others in matches he has played, while also being 57% above par on average.

The other two batters with a ridiculous record are Richards and de Villiers (yes, despite the fact that South Africa haven’t won a major tournament). Only Maxwell, de Villiers and Sehwag are quicker than the West Indian great. Saeed Anwar, Michael Clarke, David Boon and Rahul Dravid have a similar match factor to de Villiers, albeit at slower scoring rates.

Tendulkar played six World Cups – his first one at 18 and the sixth at 37 – and still managed to have a match factor north of two while scoring 20% quicker than the rest. It is a commendable achievement to maintain such consistency across eras and conditions. We see another cluster nearby, that has Mark Waugh, Rohit and Martin Crowe – three batters who are famous for their World Cup performances.

Before we conclude, it’s worth giving a shout out to batters who have done really well in this format over a small sample size. Ryan ten Doeschate has a splendid record. Gill really seems to be the next upcoming great batter in ODIs – if the format continues to stay relevant after the 2027 World Cup.

Observe one thing – there is an overlap here between previous and current era batters who have simply not played the format enough. We see the likes of Glenn Turner, Greg Chappell, Zaheer Abbas and Clive Lloyd (one of the early great ‘finishers’), and then active players such as Heinrich Klaasen, Travis Head, Shreyas Iyer and Daryl Mitchell with superb ODI records to their name. Had they played most of their cricket from the 1990s to the 2010s, who’s to say what sort of records they would have had?

So, who is the greatest ODI batter of all time? For me, the answer is quite obvious at this point: Isaac Vivian Alexander Richards. He really stands out on almost every single metric you look at. Plus, he actually missed some of his peak years playing World Series cricket, where he was also awesome. He was just made for this format, and was so good that no one could even copy him.

But I think there are fairly strong cases to be made for three other batters, even if they may not necessarily be better than Richards – AB de Villiers, Sachin Tendulkar and Virat Kohli.

These were also the final four batters we came up with when we did our 64 best ODI batters knockout video.

We could make the case that there’s not much between the peaks of de Villiers and Richards. The former dominated two eras, that of one new ball as well as two new balls. He also kept wickets in 59 of the 228 matches he played. What goes against him? He played his final ODI at the age of 33, while the others played on even after that. However, we did see him dominate the IPL after his international retirement.

Sachin Tendulkar was a plus batter for 18 years. We said this for Tests: it means India simply did not have to worry about a replacement with him on their side. He was about a par player before his peak, but that came when he was in his teenage years and early 20s. From 1994 to 2003, his numbers are like the overall careers of Richards and de Villiers. After 2004, he was still an incredible run accumulator.

Virat Kohli’s case comes from being the greatest run-chaser the ODI game has ever seen. He has this machine-like ability to churn out runs and centuries. Like Tendulkar, he’s had to deal with the pressure of playing for a cricket-mad nation. He did well before he was captain, peaked for the majority of his captaincy stint, and has been well above-par after that despite a couple of lean years in the middle.

But the case against him is simply the fact that even at his peak, he did not put pressure on teams with his strike rate the way the other three did. You could argue that was because he played in a strong side for the majority of his career, but so did Richards and de Villiers. And even though he scored the most runs ever in one World Cup – 765 runs in the 2023 edition, the other three have better overall numbers in the tournament.

Also, Kohli doesn’t have to worry about a secondary skill. Richards (five overs a match) and Tendulkar (three) could bowl, while de Villiers kept wickets occasionally (and bowled in a World Cup semi-final for some reason). I don’t know if it changes much, because Kohli also fielded in the hotspots. Perhaps de Villiers had the heaviest load here as he was either the best fielder or keeper. Richards was bowling a proper amount of overs, and was often the most important fielder too. Tendulkar was also a safe and athletic fielder in a time before India’s fielding revolution.

So, our order is:

Viv Richards

Sachin Tendulkar

AB de Villiers

Virat Kohli

Most cricket nerds would agree with the four players we have picked, while arguing about the order forever. And you could easily shuffle these guys up, because they all have great cases to be higher. But who is the fifth greatest batter of all time in ODI cricket?

Michael Bevan or MS Dhoni might be your jam if you like finishing anchors. If you’re obsessed with strike rates, it might be hard to look past Virender Sehwag or Adam Gilchrist. If you like fast-scoring finishers, you might want to think about Glenn Maxwell. We mentioned earlier that Lance Klusener was his own genre. What would we have done had he batted higher more often, and not all over the place in the batting order?

Some of the more conventional choices might include Dean Jones, Ricky Ponting and Brian Lara. What about Rohit Sharma? High-intent Rohit has been a roller coaster ride, but let’s not forget that he used to take his sweet time to get going in the first ten overs before he took over the top job. But if you love watching batters evolve over time and make significant changes late in their careers, you might just pick the Indian captain.

A lot of this also comes down to what kind of ODI players you like best. If it’s anchors and finishers, then Dhoni or Bevan makes sense. If it’s scoreboard carnage, then Sehwag, Gilchrist and Maxwell are in the conversation. But if there is anything we can all agree on, it’s that it should be Lance ‘Zulu’ Klusener, though South Africa wrongly believed he was a bowler who can bat.