Test batting strikes back

There’s a line in Jurassic World when they talk about the new dinosaur escaping from its paddock: “She is learning where she fits on the food chain, and I’m not sure you want her to figure that out.”

I’ve been thinking about this a lot while watching India destroy Bangladesh and now England demolish Pakistan. For over a century, we’ve been saying cricket is a batter’s game. Yet, there haven’t been many times when batters truly dominated. In fact, after 2000-2017 - arguably the best period for batting ever - it got really tough for batters again.

Still, we kept saying it was a batter’s game. Some of this, in Tests at least, was due to format leakage. In limited overs, where bowlers are restricted and the ball deteriorates, it makes sense that batters take over. And so they must be doing it everywhere.

Tests have always been different. Batters don’t win matches very often. There are some standout knocks, but you need 20 wickets in the end. Sure, they keep you in some matches, and without good batting your team won’t be consistent. But throughout Test history, bowlers win Tests—not batters. But right now, that’s not true.

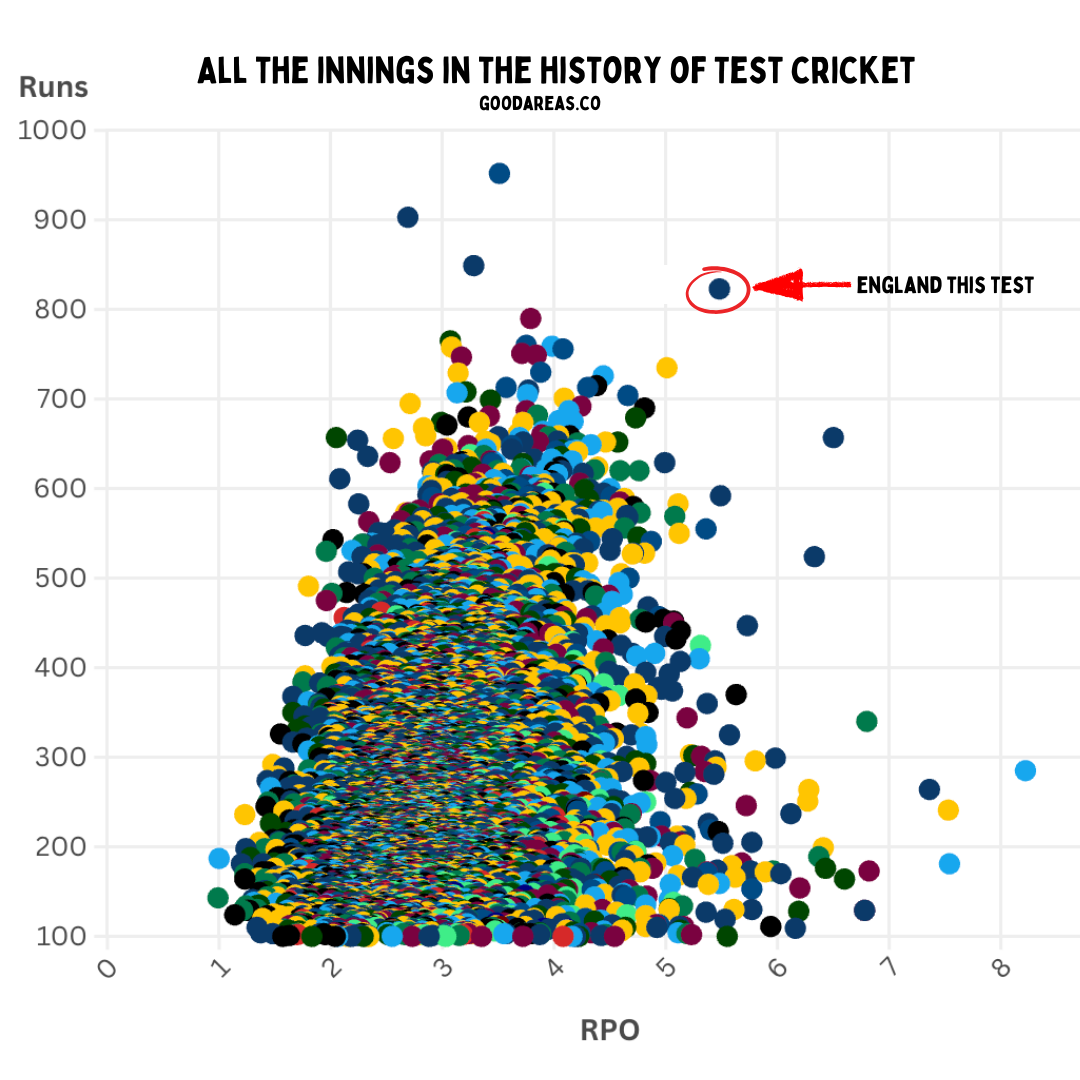

England is about to beat Pakistan by pounding them into submission—823 punches in 150 overs. Is this the moment batters rise to the top of the food chain in Test cricket?

For the longest time, batters were trapped in a metaphorical cage. We judged them on one metric: average. It looks at how many runs you made and how many times you were dismissed. Sure, hundreds were important, and total runs helped, but the average was always the first thing we looked at.

An odd part of cricket is that we know how many runs bowlers went for per over through history, but we never looked at batters’ strike rates. Bowlers were always held accountable for everything; batters only for runs and average.

Limited overs cricket changed that. Efficiency of scoring became important. No one’s saying Shai Hope is a great ODI player just because he averages 50. If anyone suggests it, his 77 strike rate gets brought up faster than any innings he’s ever played.

Even in the old days, we had fast scorers like Clem Hill or Victor Trumper, but we had no way to include strike rate in their cases for greatness. Yet, attacking batters have always been crucial.

Ian Chappell has long been a fan of attacking openers. They do two things: mess with the bowling team’s plans, forcing them to adapt quickly, and they speed up the game, buying time for bowlers to take 20 wickets. Teams have always understood this, even without focusing on strike rates.

But traditionally, Tests were still played to avoid losing, rather than to win. If you had someone like Gordon Greenidge or Matthew Hayden, they’d give your team extra time, but most sides didn’t have the bowling attacks to back it up.

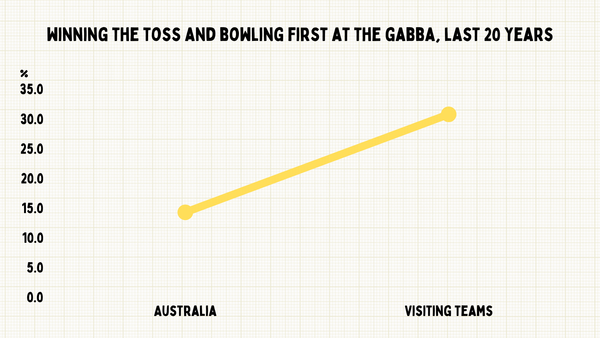

Australia did with Warne and McGrath, so they were the first team to intentionally increase their strike rate. In the late ’90s, Australia was frustrated because it was the best team but kept drawing matches. So, it decided to score quicker to give the bowlers more time.

But they could only do that with a bowling attack as dominant as Warne and McGrath. They sacrificed some runs, knowing their bowlers were the perfect insurance policy.

😱 "HOW DO YOU SCORE 556, AND ALMOST LOSE BY AN INNINGS INSIDE FOUR DAYS!"

— talkSPORT Cricket (@Cricket_TS) October 10, 2024

👀 "England batted for one over more and scored 260 more runs!"

🎙️ @FulhamJon & @ajarrodkimber in disbelief over a flattened Pakistan display! #PAKvsENG

📺 WATCH 👉https://t.co/6a1jkSSuib pic.twitter.com/etIXAQZoHp

What we’re seeing now is different. England’s current bowling attack feels like it’s been scraped from between the couch cushions, and they got hammered in the first innings. Yet England is winning by having their batters score so many runs that Pakistan has no chance left.

We discuss scoreboard pressure and how large totals mess with batters’ minds. But what do you do when you know your team faced almost the same number of balls and the other side scored 267 more runs? Pakistan wasn’t slow—they scored at 3.7 runs per over, which is fast for any era, even now. But England mocked them.

It didn’t matter who was bowling for England. The sheer weight of runs, combined with the time left, meant Pakistan had to either score 450 or block out 110 overs to save the game. Those are historically difficult feats.

If this match were played a generation ago, Pakistan couldn’t have lost after scoring 556 in the first innings unless the opposition produced a legendary bowling performance. But England batted so aggressively that Pakistan’s first innings became irrelevant.

In 1959, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower came to watch a Test in Pakistan. He witnessed one of the worst ever, as Pakistan added 104 runs for five on the day. Then it got worse. Eisenhower turned to Pakistan’s president Ayub Khan and asked, “Isn’t cricket played on grass?” At the time, Pakistan was still playing on matting pitches. Imagine the embarrassment—trying to impress a world leader and instead showing off your national obsession at its worst, on the wrong surface.

I mention this because I think it was probably the most embarrassing day in Pakistan’s Test cricket history—until today.

But, of course, Pakistan can take solace in the fact they’re part of this new era, twice now at the hands of England. History is being made, though unfortunately, at their expense. It is also funny people are saying, well Pakistan are terrible now. That is true. But Test cricket has had quite a few terrible teams - even worse than this current Pakistan lot - and no one has thought, let's score 800 against them at two runs an over quicker than any team to score this many.

This is the change we’re seeing in Tests. Teams traditionally attacked with the ball and held firm with the bat. Now, both sides can attack, and either can win it for you. That’s a whole new world.

For years, people said T20 cricket was killing bowlers. But the numbers didn’t back that up. If anything, T20 bowlers have held their own against batters. But the focus was still on averages rather than strike rates. In the last IPL and other leagues, we saw a shift. Batters realised they were the hunters.

And that’s what we’re seeing in Tests now. Batting has been unleashed.

My friend Mohammad Isam messaged me about this match: “In the scale of other sports, how insane is 823 in 150 overs?”

I couldn’t answer. Test cricket is so different. It’s hard to compare it to other sports like golf or cycling. The best analogy is that batters now are like runners after the four-minute mile was broken. For a long time, it was seen as the limit of human ability. But once it was broken, the record fell again and again. Now, it’s almost 17 seconds faster, and the women are only 7.5 seconds from crossing it as well.

But this match didn’t remind me of another sport. It reminded me of movies. Cinema existed for over 70 years before Star Wars came out. From the moment the Star Destroyer appeared on-screen, everything changed. Movies became about blockbusters, lunchboxes and franchises. Some things are so big they shift the entire landscape.

Why was I even watching Jurassic World in the first place? I grew up with Sam Peckinpah and Sergio Leone films, and now I’m watching movies designed to sell toys of made-up dinosaurs with blue stripes.

But in Tests, our Star Destroyer moment was probably Bairstow at Trent Bridge. That doesn’t mean we won’t still see standard Test cricket or some flops. But when New Zealand watched those balls fly over their heads, it felt like the start of Test batters striking back.