The follow on is a relic from cricket's past. It combines a mercy rule and something brought into the game to give us more results.

And it was so important to early cricket. The quality of the teams were really variable, which is why often one team would be allowed to play with more than eleven in their side.

But while the first follow on law existed in 1787, it wasn't the same as today. It was compulsory if you had a lead to enforce the follow on. After it was changed that if you had a lead of a certain amount, it was usually something around 100, it was automatically enforced.

There is a reason cricket did this; we didn't have a declaration. So you had three choices in these situations. Forfeit your innings, which was a significant risk, as you're now not going to bat again. Bat on and let the wickets fall naturally. Or lose wickets on purpose. This is actually what teams did a lot before.

And so the follow on made sense to move the game on.

But as declarations became part of the game, follow ons became optional. It became a tactical part of cricket. But in low scoring games in the early part of Test cricket, a lead of 150 or 200 was absolutely massive. Also, often the conditions played a bigger part, because of the uncovered wickets, making a follow on quite obvious.

Plus, in Test cricket especially, the teams were rarely well matched. Australia and England were very good, most other teams struggled.

For a long time, this was a fine system. More often than not, teams would enforce. Obviously it went spectacularly wrong on occasion. My favourite is when West Indies enforced a follow on against Pakistan in 1958. 319 overs later Hanif Mohammad had a 970 minute 337.

It is still the second-longest team innings ever played in Tests. It was on a flat pitch, and with an all-time great batter in his career knock, but it's still funny it was from a follow on.

In Mike Brearley's book 'The Art of Captaincy' he says there is two main reasons to enforce the follow on. The first is to prevent draws, which in the era of Brearley was a huge thing. The second is the psychological. "They're falling apart, attack, attack".

Brearley's book was written in 1985. Cricket was differently paced back then. And many of the opinions of the game are from that period despite all the changes since.

Like Brearley talks about the draws, we had over 50% of matches drawn in his writing years. Enforcing the follow on for that period makes a lot of sense to get results. Now, the draw rate is under 20%, and so while on occasion it matters, we enforce less than ever before and still have fewer draws.

What about the psychological? I would assume that is still there. But because Brearley is a psychoanalyst, I assume he probably rates this higher than I would. But suppose there is a psychological impact from enforcing. In that case, there is also an emotional kick from batting on, right? Keeping the entire team out on the field and setting them a scary high total is talked about as scoreboard pressure. And making them go out and field again is grinding them into the dirt.

We also need to discuss the tiredness factor.

But there is one reason why it didn't bother the West Indies as much in that match against Pakistan.

This Test finished on the 23rd of January, the West Indies bowlers didn't have to play another Test for 12 days. In fact, looking at the Tests in that series, there were five of them, six-day matches, and it took 75 days for the entire thing to be played. The closest to back to back was only seven days rest. So even though the bowlers from the Caribbean were stuffed, they had time.

In this current series between Pakistan and Australia, the first Test started on the fourth of march, the third finishes on 25 March. There are fewer rest days than the gap between the first two tests in that 58 Pakistan West Indies series. You only produce so many Test bowlers, running them into the ground is the stupidest thing.

Also, we know more about load management now, and our game is professional. From a sports science and fitness standpoint, we will rarely enforce the follow on. We do the times when it's the last Test of a series, we're rotating players for the next game, or the players have had a long break before and feel very fresh.

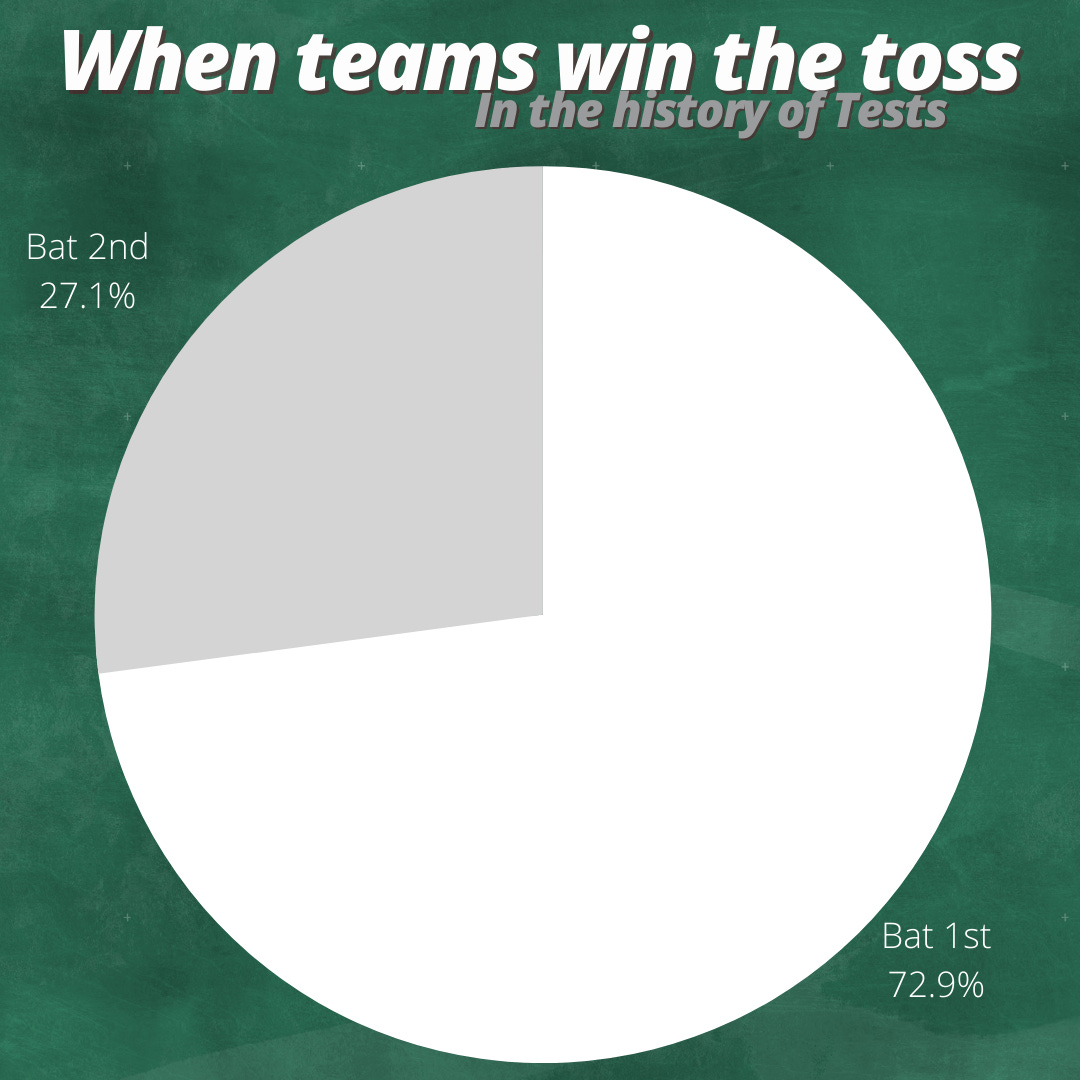

Then there is the batting in the best conditions thing. 73% of teams bat first in a Test, one of those reasons is to not bat last. If you enforce the follow on, you often give yourself the toughest batting conditions. When the it was mandatory a 100 lead was so insurmountable it didn't even make sense for a team to turn it down. Now, 200 runs isn't something as impossible. And in a series, a follow on can have ramifications way beyond that.

It's also worth talking about commentators and golf. Whether it's saying the declaration is too late or that the team should definitely enforce the follow on, commentators usually go for the more aggressive way. That is because it's not then who will be embarrassed if a team completes an unlikely chase. Most commentators would prefer to be playing golf on day four, or even day three, than commentating. I have never met a person who wants to work more hours in any job. And the third innings chip around is one of the most tedious parts of our sport.

Commentators have a huge role to play in our the public feel about the follow on. Often they sway opinion when the captain has made a tactically sound decision.

What is also overlooked too often in cricket is the fitness of the opposition bowlers. If you're playing back to back Tests, not only do you want to protect your lot, but you want to tire out the guys you're facing. Even if it's only 60 overs, that's often two spells.

I want to talk about the flat pitch theory a bit too. I have rules for the follow on. How tired are you bowlers, will not enforcing limit your chance of getting a result, how much better are you than them, and what is the pitch doing. The last one is the most important.

There are plenty of different kinds of collapses. Flukes, every play and miss is an edge, a bowler has a great spell, the opposition bat like idiots, and so many more. The best time to enforce a follow on is because the pitch played a part in it. Because unless conditions change, you're still likely to have a short innings. So often a team collapses on a flat wicket.

There was a Test in Cape Town for 2011 where Australia made 248 in the first innings, and then South Africa lost 49 runs for the loss of one. That's an average of 27 runs per wicket. Then the following 19 wickets fell for 96 runs. That's an average of five. Then South Africa made 236/2 to win the game so damn easy. The story Neil Manthorp tells me is that Gary Kirsten left the ground as coach for the birth of his child with South Africa two wickets down, and then came back later that day. South Africa were two down still, but for a few more runs, and Kirsten assumed there had been rain, not knowing in a few hours he missed two innings.

And that was a perfect example of the fact that sometimes teams just fall apart when batting. And you can see that in India's 36 all out, or Broad demolishing Australia at Trent Bridge. It is possible for excellent batting to just fold up. But it often doesn't happen in consecutive innings.

While these are rare, you can add the 2001 Test between Australia and India to this. Australia get a big total, India collapse, Australia get excited, send them back in. Then VVS Laxman - ably assisted by Rahul Dravid - set up the unlikely win.

This match is the Adam Gilchrist of follow on moments. Let me explain, Gilchrist is seen as the Big Bang of batter keepers. But in truth the game was hurtling towards keeper batters for generations before Gilchrist.

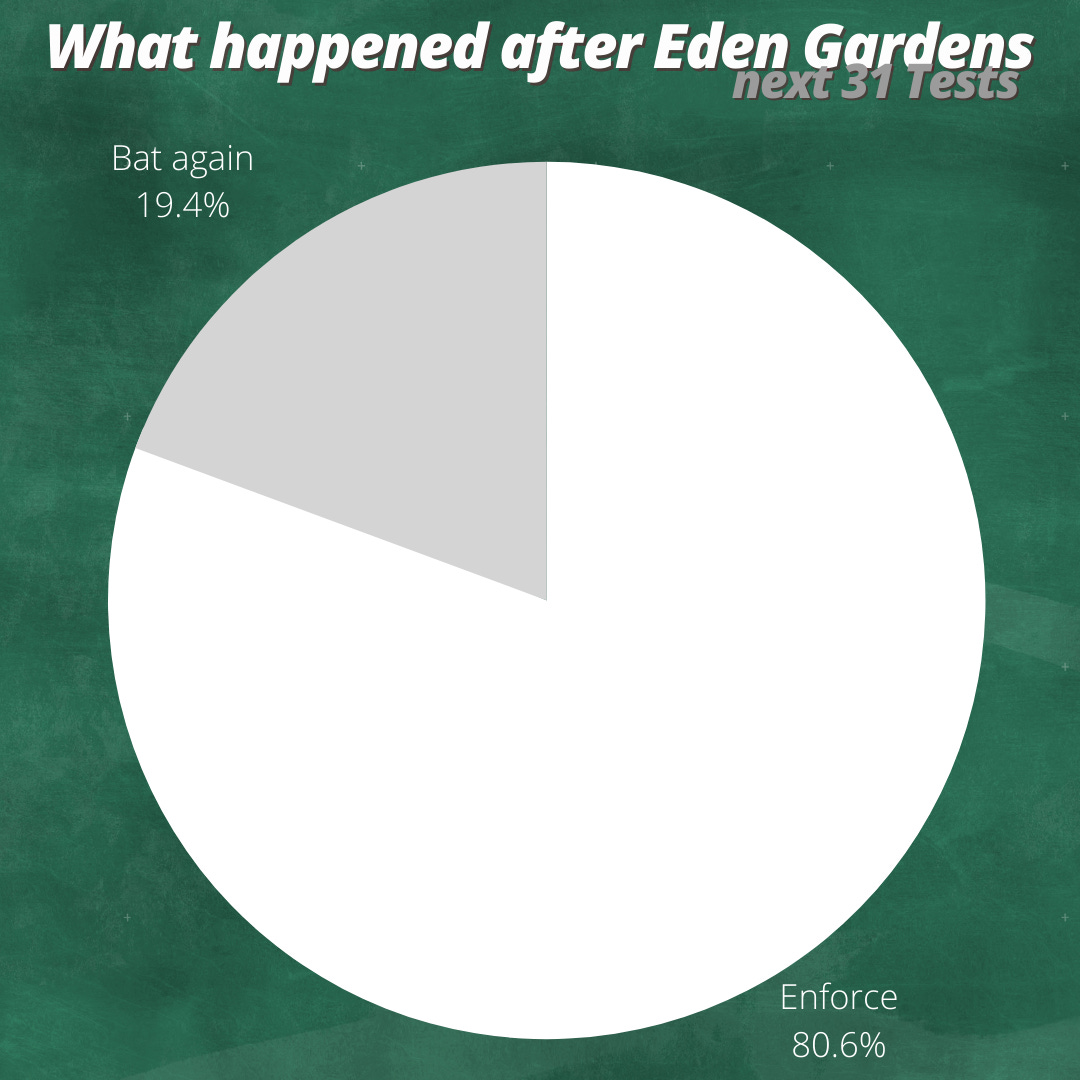

The same of the Kolkata game in follow ons folklore. It was more dramatic than most, but it was given more importance than it needs in cricket. Here is the main reason, in the next seven occasions Australia had the chance to enforce, that is exactly what they did.

In the 31 tests where teams had a chance to enforce the follow on after the Eden Gardens escape, only six times did teams not do it. It's not that it had no impact, it certainly changed perceptions, but in truth, the big change happens later.

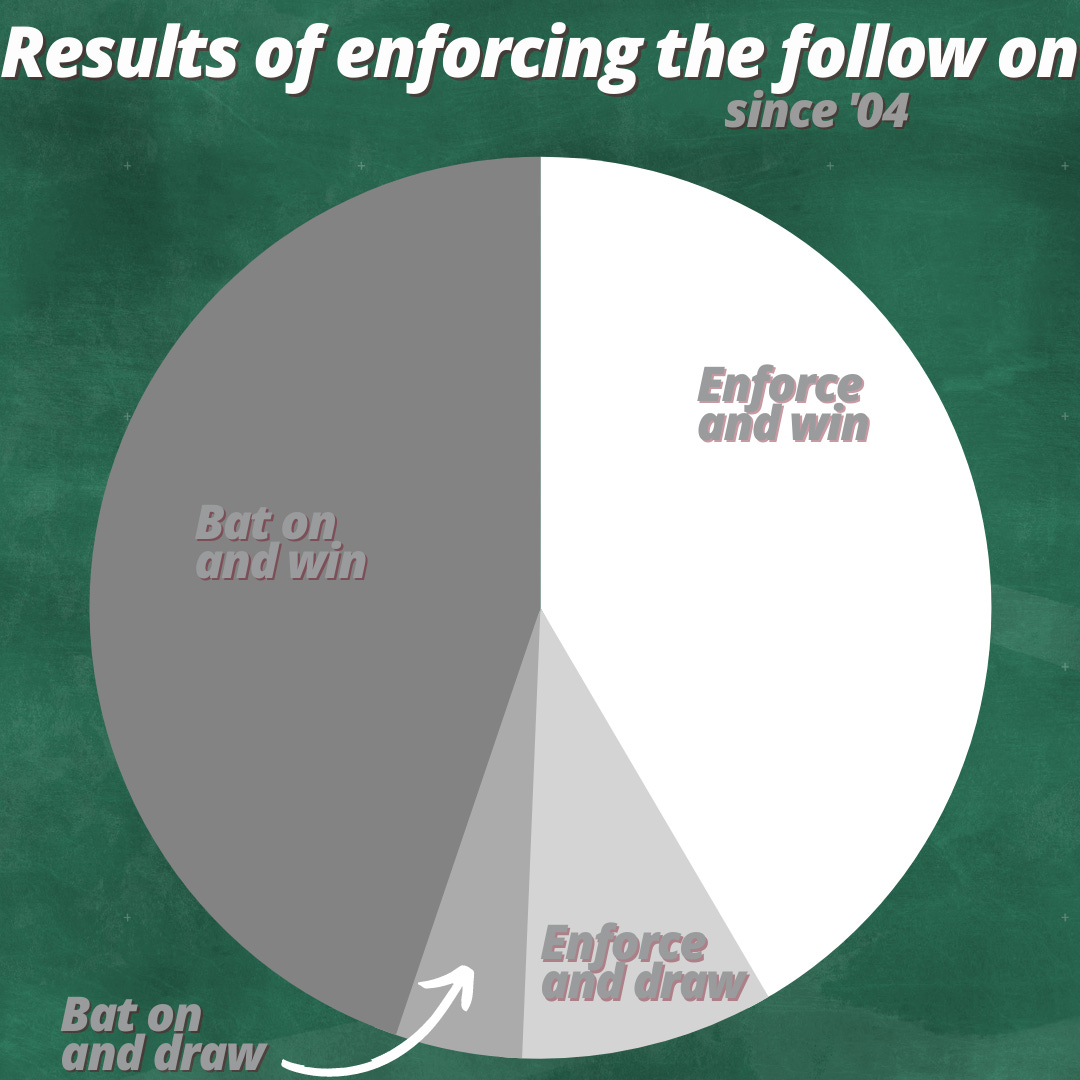

What really happened was that as the schedules changed, and also the pitches got better for batting, teams decided that it wasn't worth it. That doesn't show up really in the follow ons until 2004. From then until now, there have been two more occasions that a team has enforced than not. It's about as close to 50/50 as you can get.

There was another fun stat I saw while looking at all this. Three sides have lost after encoring the follow on. Actually, one side, three times, Australia.

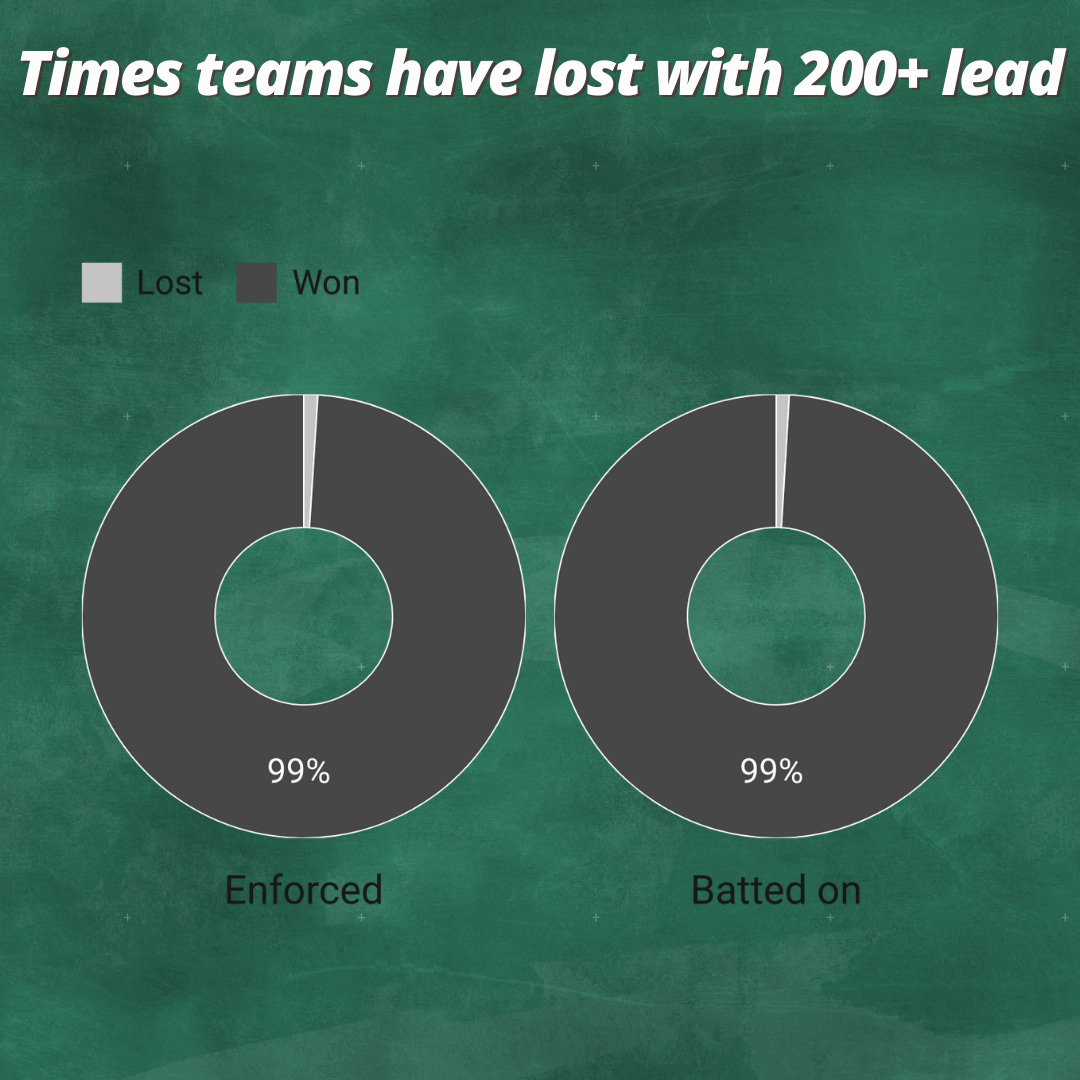

But, two sides have lost after having a 200 run lead and not enforcing. Well, again, it's South Africa twice. But one of these games was fixed and had forfeited innings, so it only happened once.

There have been 294 matches with a follow on enforced, and 107 without. And so either enforcing or not, means you lose about 1% of matches.

But being that the idea is that law allows teams to get more results, since 2004 that hasn't been the case. Of the 21 Tests that have been draws, 14 of them were after the follow on was enforced.

Put simply, the follow on is no longer needed to get results. And it's often not helpful to the bowlers. Teams are winning without it, and bowlers would rather never see it again. It will remain in our game as this beautiful relic on the past, part mercy, part tactics, and all cricket.