Why is no one making runs at night time this World Cup

Something strange is happening at this Women's World Cup. We have two different starting times: one is an afternoon game, and the other is at night. Most of the games have been played after dark, and when you watch the second innings of the late games, something becomes very clear.

No one can make any runs under the lights.

This is not the normal pattern. In the last World Cup in the UAE (the men's tournament in 2021), batting at night was what you wanted to do. Now, it’s completely the opposite. Even when teams have chased successfully under the lights, the batting hasn't been strong.

Let’s look at the games so far. In the late-start games, the West Indies chased against Scotland. That was the only time a team batted decently under the lights, but that was a massive mismatch.

England, on the other hand, chased poorly against South Africa. It was never a big task, and South Africa’s weak backup bowling let England back in. (There was also a pretty bad drop in Kapp’s last over in the powerplay.) Despite this, Nat Sciver-Brunt — one of the most brutal batters in the world — was surprisingly timid. What should have been a net run rate blitz turned into a slow burn.

When England batted first against Bangladesh, it was another mismatch, but a weird game overall. England batted poorly in the first innings. Bangladesh were probably never going to chase it down (thanks to Glenn and Ecclestone). However, Bangladesh weren’t bowled out and still didn’t make it to 100, which shows how tough the conditions were.

Australia’s game against New Zealand was interesting. The Aussies looked set to post a total of around 175 but then collapsed. It looked like the conditions changed mid-innings. But, no one could hit the ball off the square when New Zealand came out to bat. Losing to Australia is fine, but New Zealand looked like they didn’t even belong on the field.

That’s surprising, considering that New Zealand had pulled off a huge upset against India just one game before. And their batting set up the game. Sure, Australia has a better bowling lineup. But when the Indian batters faced a much weaker KIwi attack, they looked completely out of their depth. And usually, I would have blamed them.

In the game before that, Pakistan scored over 100 largely because Sri Lanka failed to take the last two wickets. It should have been an easy chase for Sri Lanka, but it looked like they were chasing 300, not 117.

In another night game, Sri Lanka chased against India. They were never really in the game, but the fact that they got close to 100 was a big achievement. They seemed to be losing a wicket every ball to start the game.

What’s fascinating about these first seven games is that there are two pitches. This isn’t just about one rogue deck; it's more than that.

Teams have chosen to bowl first at night in the last couple of years. But in this World Cup, every single team has decided to bat first. The teams figured something was up from the very first toss across two different pitches. And they were right.

My first thought was that everyone seemed to be getting bowled. The ball is skidding on like crazy. Slower spinners are tossing it up, and it’s still sliding through. If you look at the entire World Cup, there’s a slight rise in the percentage of bowled and LBW dismissals.

However, the difference is striking if you compare the first innings to the second innings in just the night games. There's more than a third more LBWs and bowled dismissals in the second innings. That’s a significant increase. In the first innings, it's normal; in the second, it's nearly impossible to survive.

In women’s cricket, there tend to be more bowled and LBW dismissals in general. A big reason for this is the height of the bowlers — they’re shorter, which keeps the stumps in play. So, if the ball is skidding more at the end of these games, it's easy to see why batters are struggling to keep it out.

However, this doesn’t explain why, if dew is making the ball skid, we’re not seeing the full tosses that often plague men's games in these conditions.

Other factors contribute to the higher number of bowled and LBW dismissals. One is that women don’t play as much under lights. Many women’s franchise leagues have early double-headers, and there are more day games. Overall, they play only about half as many night games as the men do.

Catching a ball at night is also very different from during the day. Most cricketers try to catch a few balls at each venue to get used to the conditions. However, it’s hard to do that during a tournament, and teams are often not allowed to train at night. As Vishal points out in his piece, the “ring of fire” lighting setup in Dubai is particularly difficult to adjust to. That explains the higher number of dropped catches at night but not the poor batting averages.

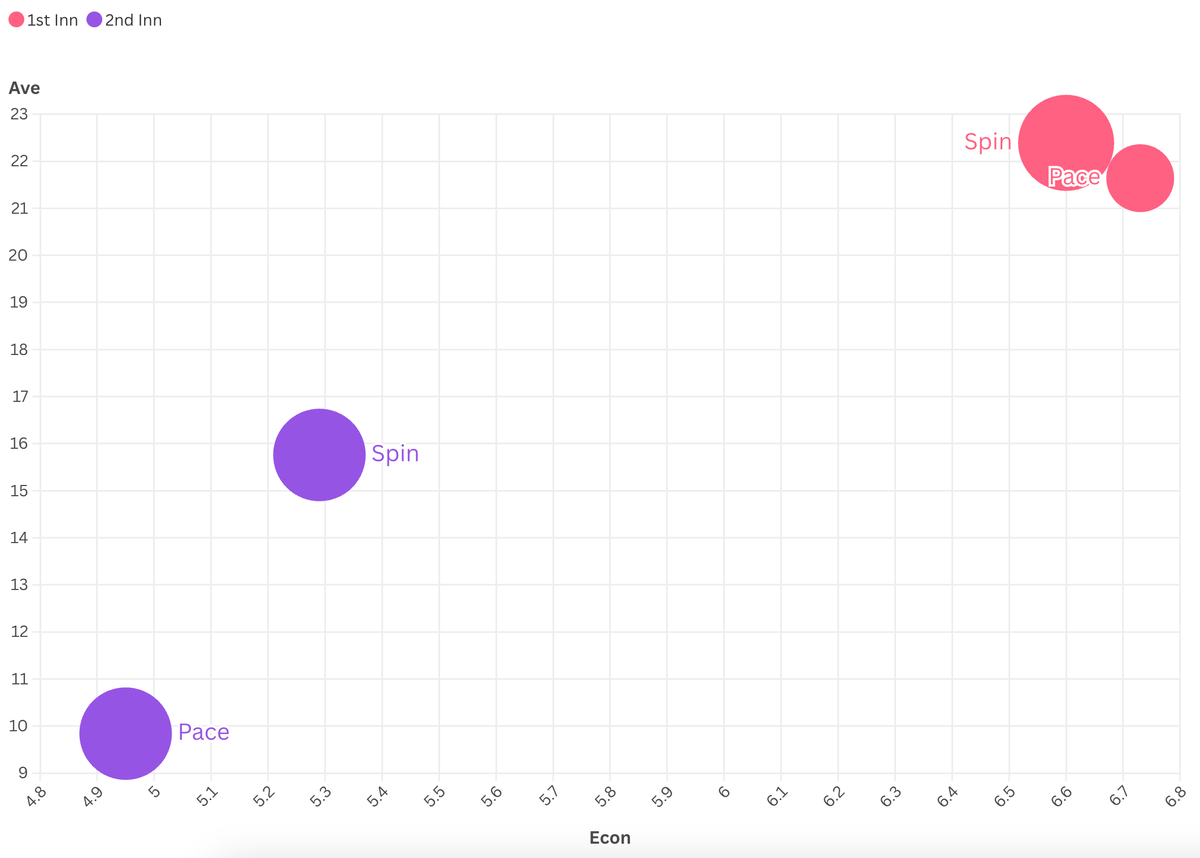

Pace vs. Spin in Night Games

In the first innings, both pace and spin are going for about 133 runs per 100 balls, while picking up a wicket every 23 runs or so.

In the second innings, however, as the temperature drops, the ball usually skids onto the bat better. This benefits men’s teams, but the women are struggling. Against spin in the second innings, women’s teams are scoring at less than a run per ball and averaging in the high teens.

But the real issue is pace. In the second innings of night games, the scoring rate is under five runs an over, meaning the average score is just 98. But the average against pace is more shocking: batters are averaging under 10 runs per wicket. It’s like they’re barely batting at all.

This aligns with what we’re seeing on the field. Good batting lineups look like crash test dummies in the second innings under lights.I find fascinating

I find fascinating how different this Women’s World Cup is from the men's tournament in 2021. In 2021, the Super 12 stage became all about the toss, with teams opting to bat second due to the dew. Slower balls and spin were almost impossible to control, leading to more wides and a loss of accuracy.

This year, it’s the opposite. The spinners and seamers are deadly accurate, with nearly half the wickets being bowled or LBW. And when the moisture comes in, good luck to the batters.

The strangest part? In the seven night games we've seen so far (which could mean nothing), the ball gets moist enough to skid, but not enough to slip out of the bowlers’ hands and turn into full tosses.

Either way, batters should be very afraid of the dark in this World Cup.