Woman of books

My mother, the library technician

My mother finished high school and did a heap of meaningless jobs. Then she had a baby, and like many women, she spent a few years wiping my ass and making sure I was kept alive. It was an ordinary experience, but it all changed when she had to find a job.

The job she found was in a library at a Catholic School in Broadmeadows.

Broady. The rough part of town. A part of town that books aren’t synonymous with.

There, in Broady, with a bunch of boys more interested in sports, girls and fun times, my mother founder her calling, she loved books and kids.

With secondary kids she felt like she was an important part of their development. She loved research, and would find articles and books that would help them pretend to be intelligent during reports and essays. While my mother loved this part of her job, those essays and reports are largely bullshit. Regurgitated “wisdom” hacked into chunks for teachers to grade. It teaches smart kids how to fake it, and never pushes them. And gives hope and encouragement to dumb kids who crack the code.

That wasn’t what my mother was really good at, her real gift was making people love books. She would create these epic no budget displays about a theme or genre, and sell the kids on books. There would be pitctures of robotos and monsters around a bunch of sci fi books, or sporting images around the sports books. And these kids would buy it up, and they’d start reading. And I know how well it worked, because she did it on me.

As a kid, I had always been into writing. Even if I hadn’t noticed it myself. There probably aren’t many six year olds writing their own Shirley Temple scripts. But it wasn’t just writing I was into, I also had a love for weird shit. Now I didn’t notice it at the time, or really for years later, but my mum noticed both of these things, and, at a very young age, she fed me this weird shit. Because that’s what made me read. Books about people with eyes like cows. People who ended up in video game worlds that could kill them. And Z for Zachariah. Which was a book about a young girl who may or may not have been potentially raped by some nuclear guy who survived an apocalypse.

Not to forget Taronga, which is a guy who talk to animals in order to eat them in a post-apocalyptic Sydney. Many parents would be worried about these sorts of subjects, my mum found these books and fed them to me before I was ten.

And I loved them. She was doing all the hard work for me, all I had to do was read them.

My mum knew me. There was no point giving me books that were aimed at kids my age, or that were part of the curriculum, she found the books that would appeal to me. That was her skill. It wasn’t just me. She did it with guys I played cricket with. She did it with kids I knew. She did it with kids at her school. She was desperate to find books for kids.

She sold books to young aussie boys who just liked hitting, kicking, swearing and wanking. In a culture where being intelligent was seen as being a pussy, she made us all read.

She did it at tougher schools, my old school (which the library had to be closed down because the boys piss had seeped through the connecting wall). My mother pushed books in Broady, Epping and Craigieburn (Fuck Craigieburn). Three places were book learning is not exactly supported. But that never seemed to bother her. Or worry her. Or even occur to her. Kids who didn’t speak English at home. Kids whose parents couldn’t read. Kids with every kind of background. The troubled kids. The gifted kids. The drifting kids. She saw it as her mission to find books that would challenge and books that would inspire.

When they wouldn’t read, she’d find a way to trick them into reading, and most of us loved her for it.

Every kid was one book away from reading. She would try as much as she could to find that book. She probably never thought about it, as my mother is not one for quiet introspection, but it became a mission for her. It was not beyond her to buy in a book for just one kid, because she knew that could reach them, change them, help them.

My mother has a drive in her that not many people have. She helped set up a theatre company in a part of town that considers the theatre as something for ‘poofs’. She helped run cricket clubs when women were supposed to provide teas and shut up. She was in charge of two school councils and library clubs. And she is still about 16 years into her role as president of the Epping Tennis Club. Had she come from the ‘right kind of family’ she probably would have been the CEO of a big company, or in politics. Some may say she did better than that.

In her rare spare time, often well past midnight, she reads. Papers. Magazines. Books. Everything. Sometimes I remember her just reading catalogues of kid’s books, looking for that one book, for that one kid. Her energy is scary; her drive is never ending.

My mother was wasted as a school librarian. Trying to get young boys to read something other than the sport section. Or young girls into something other than trashy magazines. She should, and could, have done much more. But she was a girl from North Melbourne and Braybrook with no higher education; she was not even technically a librarian in a paperwork sense. She was a library technician, or something of that nature, but paperwork wouldn’t change what she really was.

An educator. An Inspirer. A woman of books.

I am sure she has helped people become lawyers, actors, politicians, doctors and artists. Many of which will have forgotten their passionate loudmouth librarian who made the displays that first got them interested in literature.

But I haven’t forgotten. Because she was always there for me. Always suggesting new books. Always pushing me to read. Always pushing me to learn. Always pushing me to grow.

Where I came from ambition often seemed like a dirty word. It was working class and hard. And those who stuck their head up too high got a smack across the neck. But I remember once writing out a list of my dream jobs.

It was:

Writer.

Director.

Musician.

Cricketer.

Work in a CD store.

My mum skipped down the list past the first four, and got stuck on the last one. “You don’t really want to sell CDs, do you”. And I didn’t, hence why it was number five. But she wouldn’t even let me have a fallback. Like most of the kids she looked after, she wanted nothing but the best. Wouldn’t even accept that we wouldn’t try for that.

When I was 19, I left gardening school after three months. My parents were not amused. A pretty violent argument ensued. My dad left the room in disgust. My mum regained her cool and asked what I wanted to do next.

“I want to be a writer”.

“Well, you will be, but probably not till your 30”.

I was a 19 year old high school drop out that failed English, had been fired from factory work, been a shopping trolley attendant and now couldn’t handle learning about plants. There was no reason to believe that I could ever become a writer. Or, anything.

My first book was published when I was 29.

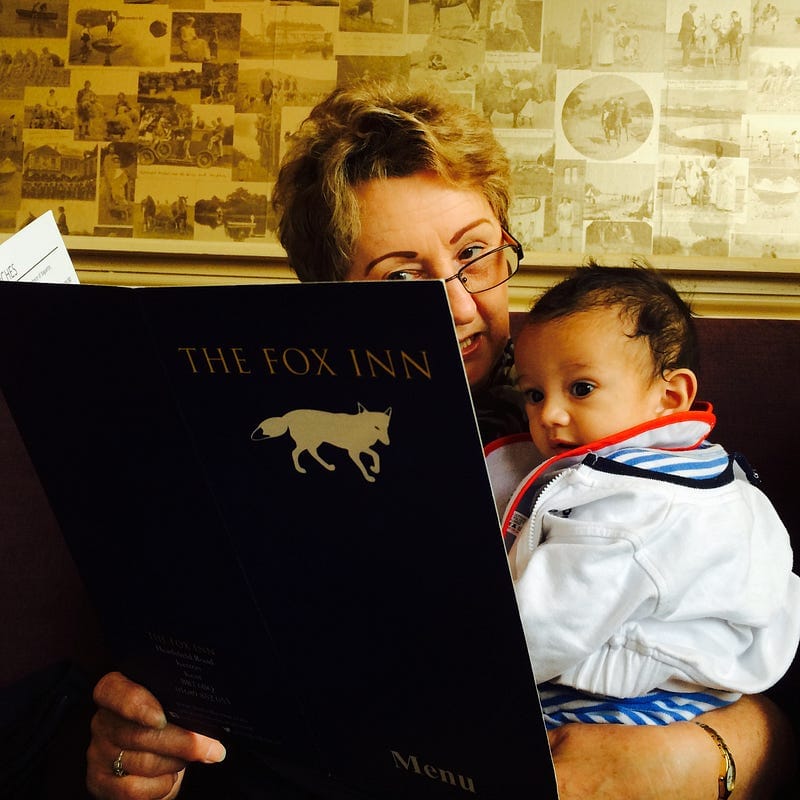

My mum has now retired from her job. The school gave her a great send off. One worthy of her passion and dedication. Because of my job, as a writer, she got to do it with her grandkids by her side.

But that was not enough for me. I wanted her to know, on behalf of all of us that she gave the books to, that she was something special. That she really meant something. And even for all those who have moved on and forgotten her, she was a part of their journey. That she had a part in their learning. Their improvements. Their achievements. Their origin stories.

My mother is special. And she won’t ever get the credit that she deserves. I, and probably many others, owe her a massive debt, Other than the obvious actual birthing if me, I know I wouldn’t be where I am without her. I wouldn’t even be close.

She believed in people when no one else did. She is a hero. She is a legend. She deserves a standing ovation at the MCG. A bouquet of flowers on stage. An award from her peers.

Instead all she gets is this rushed thank you from her son. But more than me, I hope somewhere, there is one of her students, who on a good day, when they love their life, they wonder what ever happened to that woman who loved books, who showed them that book that they still remember, who made them read. And then they smile.

I have no doubt there is someone out there who remembers her, who was changed by her. She was a lot of things, ordinary wasn’t one of them, like the many, many before her, she proved that librarians, and even library technicians, can be heroes. I know one who is.