Women's cricket is about spin and space

We look into how the women's T20 is different from the men's.

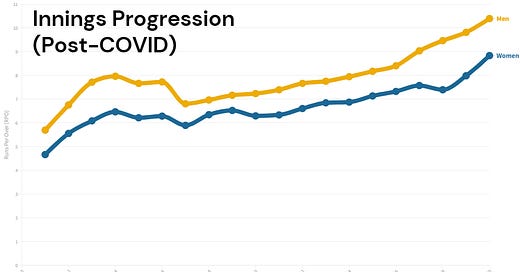

This is the shape of the men's and women's games. You can see here how many runs per over each of the elite T20 teams and competitions allow throughout a match. And they look similar, but there is one very noticeable difference. After the powerplay, men's cricket has a significant drop, while the women actually start scoring quicker.

Women's cricket has key differences that not all fans know about. The obvious one is that the ropes are in more, which is really easy to see. But also the inner ring is smaller. For men, it is 30 yards, for women, 25 yards. And this seems to have an impact on the rest of the game. For years there were more run-outs, as women tried to steal ones with fielders five yards closer.

And even now Hypocaust has talked about how the new regulations to bring fielders into the circle for slow overrates actually have a negative impact on the women's games. Especially if top-order players are not in. The result is often that tail-enders, who can't time or power the ball as well, are given fewer gaps to pierce.

The other key difference is that women use a smaller ball. Some players think it should go lighter still. It makes it easier for women to bowl spin, and they bowl a lot of it; In the post-COVID era, about half of all deliveries in the women’s game were bowled by spinners. On the other hand, the usage of spin is much lesser in the men’s game.

In all three phases of the women's game, spin is crucial. Most notably, spinners are some of the best death bowlers in the world. In our preview of the T20 World Cup's top bowlers, Jess Jonassen was mentioned. I'm still trying to figure out what makes her so special, and I'm not sure I understand it completely. She is incredibly astute, precise, and composed. There isn't much mystery there. But she makes excellent bowling decisions. And when the batters miss, she hits.

But being that it isn’t just her, it perhaps has something to do with batters coming in down the order and struggling to power away spinners. The place off the ball seems to have a far bigger impact in the women’s game where there is less power.

You can see that women bowl more than double the amount of spin at the death. And yet almost the exact same amount in the powerplay. That is a big step up, and it’s not like you often see in the men’s game where it is a couple of spinners doing it, this is widespread across the women’s game. Rashid Khan is probably the only exception to the norm. And he doesn’t even make it to the top 20 bowlers in terms of overs bowled. So if you are playing women’s cricket and batting at the end, you have to be able to play spin. But being that it is practically half the balls in all the matches, no matter where you bat, there is no hiding from spin.

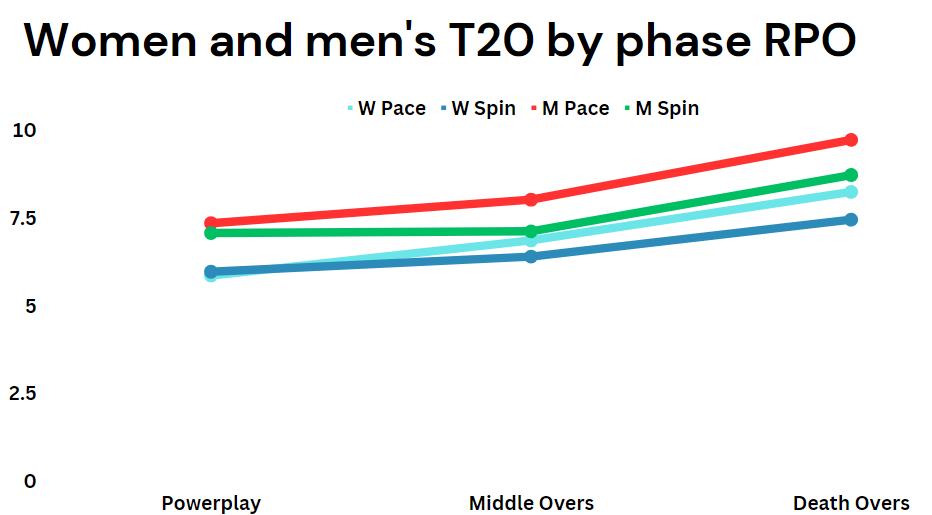

Now let us look at runs per over. The only time that the spinners are worse in a women’s match is in the powerplay. The one time the field is up. Even at the death, with their high usage, they are still well below anything that seamers can bowl. And this isn’t Asia warping the numbers either, because in these numbers it is most non-Asian franchise numbers. So with PSL and IPL, it could actually change more towards spinners.

If you drop the men’s games in here, you see the pattern is really similar.

But there are key differences. The men don’t score quicker against spin than pace in the powerplay, even if the fielder in the circle plays a big part. The other difference is that spin in those middle overs has a far bigger drop in runs per over than it does with women. And you will see one of my favourite things, that spin at the death has a lower econ than pace by heaps. That is partly because spinners only tend to bowl at the death when the wicket is ragging. But it might also suggest that spin isn’t bowled enough at the end.

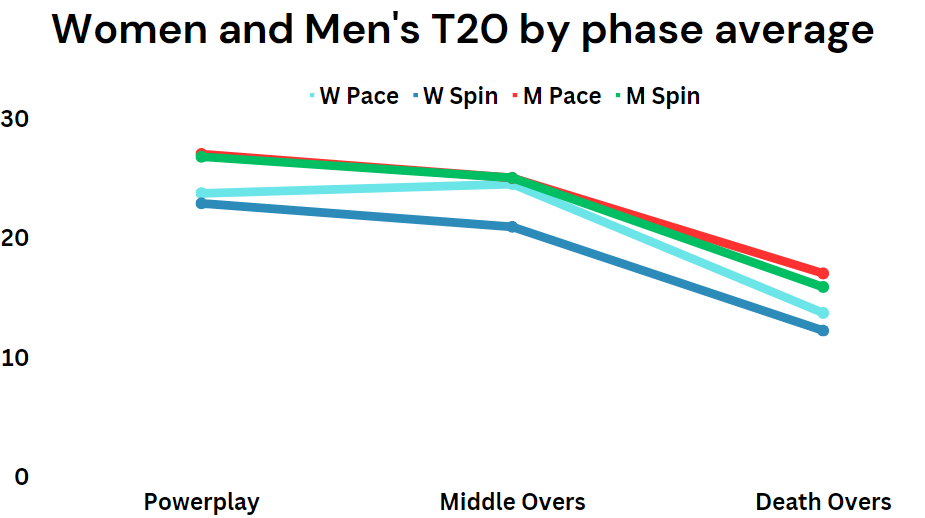

And by average, the spinners are better in all three parts of the game. Often in the men’s game the averages balloon for finger spinners in the middle overs. That doesn’t happen here. They are wicket-taking machines. And even in the powerplay, their weakest phase, they are outperforming women swing bowlers, which takes some effort.

If we drop the men in here we see that in terms of average, there is no big advantage for spin or pace all the way through the innings.

They are almost identical all the way through until spin has a better average at the end. But look how different the women’s lines are. Their spin is clearly better in terms of averages, and the men it is all about the same. So women already bowl a lot more spin than men, and by this, you could argue they could use even more. If Australia wanted to, I am pretty sure they could bowl Asheligh Gardner, three leggies and Jonnassen with one seamer and be even better.

Most of the best women players at the death are anchors - Laura Wolvaardt, Harmanpreet Kaur and Beth Mooney. Their strategy is very similar to men’s ODIs - knock it around in the first 15 overs with the odd boundary and party hard at the death. In men’s cricket, we have a lot more specialist middle-order hitters.

As of now, there are few mavericks who actually specialize at the death overs hitting. Annabel Sutherland comes to mind. Richa Ghosh showed potential at the World Cup, but in truth, there is a lot more development required in her power-hitting game. This also explains why the top-order batters tend to be a lot more conservative about their game.

Usually, when people talk about women batting they say the tails are weaker. But the actual problem comes in numbers 5-7. They only score about 17 runs per dismissal at 6.59 runs per over. They do not offer a strike rate trade-off yet, hence there is a lot more pressure on the top order to preserve their wicket at the top and maximize the death overs.

Look at it compared to the men.

They get a bump in strike rate and average in that section. This is something I expect to improve soon. But women’s cricket is far more reliant on their top order batting long.

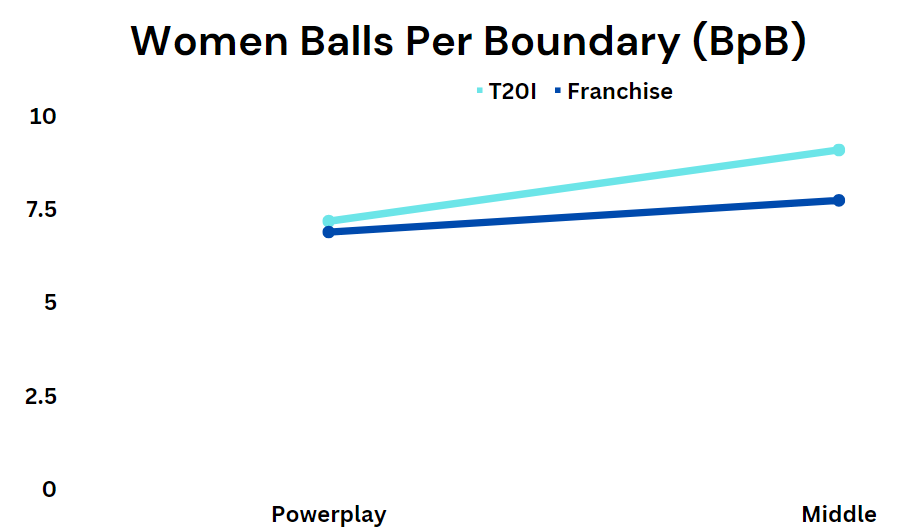

This brings us to balls per boundary. There is something interesting to note here. We now know that the strike rates of women batters increase in the middle overs. However, it is worth noting that the rate of hitting boundaries takes a significant dip. This implies that the strike rotation improves a lot more in this phase. There is nothing here you wouldn’t find in men’s cricket. However, the big difference here is between franchise and international cricket.

Teams tend to field their best bowling attacks in international cricket. So maybe this is why the BpB measure is higher in international cricket than at the franchise level. And we aren’t using all T20Is, because obviously the standard changes. So it’s only teams that have qualified for this world cup. But in the middle overs, the BpB is 17% more in international cricket than in franchise cricket. That is a huge difference and in men’s cricket, you don’t tend to see differences like this.

All this brings us back to the fact that women score quicker in the overs after the powerplay than men do. When you put the fielders back and men start hitting boundaries every 7.5 balls, more than two balls more than in the powerplay, their run rate is affected. When you do it with women, the balls per boundary go up, but instead of the econ going down like men, it goes up.

Women score quicker with fewer boundaries. This for me is the pattern that is most interesting. This is a completely different form of batting. The men are playing a power game, the women are playing a space game.

Piece written by Jarrod Kimber and Shayan Ahmad Khan.

I may be completely wrong Jarrod, but you don't mention the reason that I'd always assume spin bowling is more frequent in (elite) women's cricket - the simple fact that once you remove absolute pace from the women's game, a key reason for the strength of pace bowling in the men's game disappears.

Consider:

1. Men and women still face the bowler from 22 yards away

2. Men and women have identical reaction times scientifically, so women should in theory be able to "react" to face face bowling equally well (I accept that this is diminished somewhat that women don't actually play raw pace as well simply by never actually facing it, but the theory of the nervous system and reactions are identical).

3. Women's spin bowling pace does not drop off compared to the men, in the same proportions that it does for pace, as such the relative "value" of pace bowling in the pure sense that it forces batting decisions in a reduced amount of time is reduced.

It's a similar thought experiment that if every man who could bowl quicker than 130kmph (and every spinner who typically bowl quicker than 90kmph for balance) disappeared from earth overnight. Of course some new pace bowlers would be selected, but undoubtedly the proportion of spin used in men's cricket would also increase should these cricketers disappear.

This identical "absolute dimensions" can also be seen in in tennis, where the fact that men and women play on the same sized court results in slightly different biases toward height/mobility (if we assume it to be on a continuum). The average male pro tennis player is "only" four inches taller than the average man, but the average professional women's tennis player is about six inches taller than the average women - suggesting that there's somewhat of a "sweet spot" in terms of height/mobility equal across both genders due to identical dimensions of the court for both players.